Dangerous legacy: Tens of thousands of Coloradans live near one of the state’s many underground coal-mine fires

VGhlIE1hcnNoYWxsIEZpcmUgZW5ndWxmcyBhIGhvbWUgaW4gTG91aXN2aWxsZSwgQ29sby4sIFRodXJzZGF5IERlYy4gMzAsIDIwMjEgYXMgY3Jld3Mgd29ya2VkIHRocm91Z2ggdGhlIG5pZ2h0IGJhdHRsaW5nIHRoZSBibGF6ZSB0aGF0IGhhZCBkZXN0cm95ZWQgbW9yZSB0aGFuIDUwMCBob21lIGluIEJvdWxkZXIgQ291bnR5LiAoVGhlIEdhemV0dGUsIENocmlzdGlhbiBNdXJkb2NrKQ==

Q2hyaXN0aWFuIE11cmRvY2svVGhlIEdhemV0dGU=

The veins of mining run deep in Superior, a Colorado community founded on coal and recently redefined by fire. For generations residents needed only to go a few miles west during winter to see plumes of steam and smoke rising from fissures in the Earth, from an underground coal mine fire that started before many of them were born.

Investigators are now looking at that coal mine fire — one of 38 monitored by the Colorado Department of Natural Resources — as a possible cause of the Marshall fire, which on Dec. 30 swept through town and burned 95% of the original portion of Superior and some homes inhabited by the descendants of coal miners.

“I think the coal mining industry is so filled with dangers that there are a lot of ironies,” Superior Historical Commission Chairman Larry Dorsey said.

The Marshall fire was first reported at a spot near the Marshall Mesa Trailhead, about five miles west of Superior, in the late morning of Dec. 30. Within minutes of its discovery, hurricane-force winds had whipped it into an inferno that stormed east through kindling-dry open space. By the time a heavy snowfall ended the blaze a few hours before the new year, 1,084 homes were destroyed, 1,500 acres had burned and two people were dead.

A sign posted at an entrance to Marshall Mesa announces the closure of the trailhead after the Marshall fire, as seen last week in Boulder. Multiple trails in the open space reopened Friday.

Timothy Hurst, the gazetee

A sign posted at an entrance to Marshall Mesa announces the closure of the trailhead after the Marshall fire, as seen last week in Boulder. Multiple trails in the open space reopened Friday.

The investigation into the most destructive fire in Colorado history remains in a “holding pattern” as the Boulder County Sheriff’s Office awaits the lab and expert reports that will help determine a “final conclusion,” spokeswoman Carrie Haverfield said, on Friday. Her office announced in late January it was investigating “any and all potential causes of the fire including coal mines in the area, power lines, human activity, etc.”

Whether or not the coal mine fire burning beneath city of Boulder open space is to blame, the fact remains that such underground fires stalk many Colorado coal towns — and have, in the past, sparked destructive wildfires.

A warming, drier climate means even “low activity” underground fires pose a greater risk of becoming a monster, should flames breach the surface.

In total, tens of thousands of Coloradans live within just a couple miles of one of the state’s underground coal mine fires, a Gazette analysis of census data showed.

“Anywhere you have historic coal mining and the right kind of climatic and geologic conditions you can certainly have fires,” said Jeff Graves, program director of the Inactive Mine Reclamation Program with the state Division of Reclamation, Mining and Safety under the state’s Department of Natural Resources.

There are more than 1,000 historic coal mines in Colorado. All of the coal mine fires Graves and his team are currently monitoring began prior to 1977, when the federal Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act changed the way coal companies do business.

An underground coal fire burns near Wise Hill in Moffat County. (Source: Colorado Division of Reclamation, Mining and Safety)

An underground coal fire burns near Wise Hill in Moffat County. (Source: Colorado Division of Reclamation, Mining and Safety)

“There was a recognition that if we’re going to keep operating a mine here we need to be conscious of the potential of igniting a coal mine fire,” he said. New federal regulations “really addressed a lot of those concerns associated with ignition.”

Some fires are remote, far from where people live, and others are on the edge of towns. One lies within the city limits of Cortez.

And while some of those underground fires are considered to be low or very low activity by the Department of Natural Resources, they’re situated in wildfire-prone areas, according to the U.S. Forest Service’s “wildfire hazard potential” evaluation system.

The Marshall and Lewis underground coal mine fires, which sit almost exactly where the devastating Marshall fire began, have some of the closest residential areas, with more than 6,000 Coloradans within two miles, prior to the fire.

The Department of Natural Resources classifies both of those as “low activity” fires, but they’re in above-average “wildfire hazard potential” risk areas.

The McElmo underground coal mine fire burns on the southern edge of Cortez, within a couple miles of nearly 9,000 residents. According to the Department of Natural Resources, the fire has “very low activity but high risk of trespassing.”

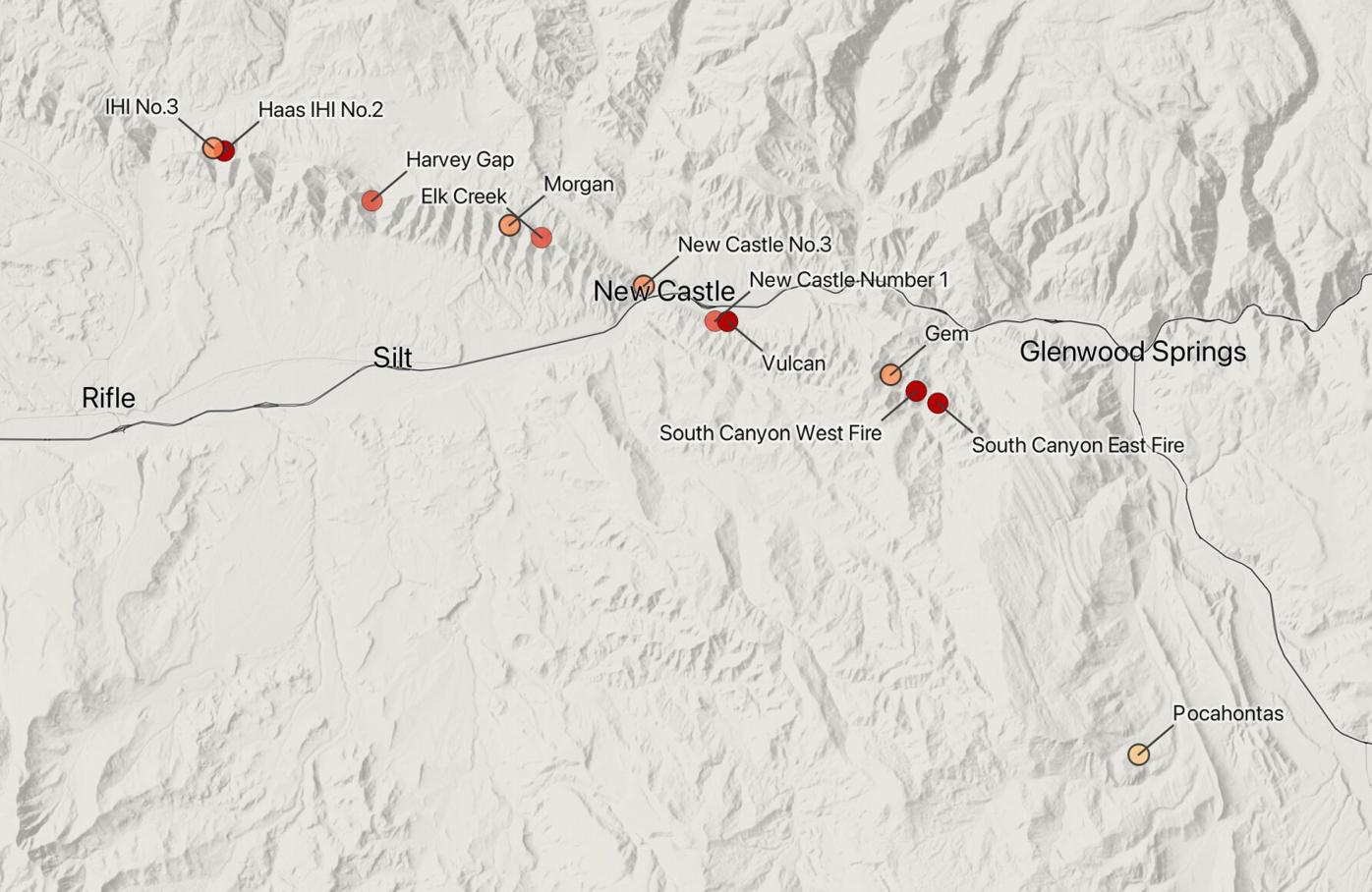

Underground coal mine fire activity across Colorado

Underground coal mine fire activity across Colorado

The area west of Glenwood Springs is relatively dense with underground coal mine fires, especially around the small town of New Castle, 13 miles west of Glenwood Springs, where three underground coal mine fires burn on the periphery of a 2-mile area that’s home to almost 6,000 residents. The state deems one of the fires to be of low risk, one medium risk and one high risk.

Management of the South Canyon Coal Mine Fire with the Inactive Mine Reclamation Program of the Colorado Division of Reclamation Mining and Safety.

The South Canyon fires, about a 20-minute drive west on Interstate 70 then south on County Highway 134 from Glenwood Springs, are both considered “highly active,” with new vents forming and vent temperatures between 500 degrees and nearly 700 degrees Fahrenheit. The department notes they are also close to trail systems, where signs have been posted to let hikers know what they’re seeing is the “off-gassing” of an underground fire:

“Coal Seam burning underground. Do not call 911.”

Smoke can be seen billowing from the South Canyon underground coal mine fire burning west of Glenwood Springs. (Credit: Colorado Division of Reclamation, Mining and Safety)

Smoke can be seen billowing from the South Canyon underground coal mine fire burning west of Glenwood Springs. (Credit: Colorado Division of Reclamation, Mining and Safety)

In 2002, that coal mine fire sparked a wildfire that burned 12,000 acres and 29 homes in Glenwood Springs.

FILE - Damage from the Coal Seam fire in Glenwood Springs, Colo., is shown on June 9, 2002, An area outside Denver where Colorado's most destructive in history wildfire burned 1,000 homes last month is home to numerous abandoned coal mines that authorities say could be a potential cause of the wind-driven wildfire. History shows that the moldering coal have started fires before, including near the same location south of Boulder in 2005, when a hot vent from a burning mine sparked a brush fire that was quickly extinguished. A coal mine fire also ignited a blaze in the Colorado mountain town of Glenwood Springs that burned 29 homes in 2002. (AP Photo/ Peter M. Fredin, File)

PETER M. FREDIN

FILE – Damage from the Coal Seam fire in Glenwood Springs, Colo., is shown on June 9, 2002, An area outside Denver where Colorado’s most destructive in history wildfire burned 1,000 homes last month is home to numerous abandoned coal mines that authorities say could be a potential cause of the wind-driven wildfire. History shows that the moldering coal have started fires before, including near the same location south of Boulder in 2005, when a hot vent from a burning mine sparked a brush fire that was quickly extinguished. A coal mine fire also ignited a blaze in the Colorado mountain town of Glenwood Springs that burned 29 homes in 2002. (AP Photo/ Peter M. Fredin, File)

Graves said some of the fires his team monitors began prior to 1900. Experts can only speculate at the cause in most cases. Spontaneous ignition can, and does, happen. A spontaneously generated coal seam fire in Australia is thought to have been burning for more than 6,000 years.

While anecdotal stories exist, of fires ignited by miners’ candles and lamps, “generally, we believe it to be just that natural chemical oxidation process that over time creates combustion,” Graves said.

Glenwood Springs Fire Chief Gary Tillotson said his crews drive out to check on the active coal fires in the area regularly in the summer as residents and visitors call 911 to report smoke.

Usually, the underground coal fires are just venting. But he doesn’t mind sending crews out again and again to check the area where the 2002 Coal Seam Fire started.

“It definitely is not any less of a threat,” he said.

While the burn scar is still visible near the underground fire, unburned areas remain north and south that could carry a fire. In addition, most of the homes lost in 2002 have been rebuilt and new apartments have gone up in the area as well that could burn, Tillotson said.

Following record-setting fires on the Western Slope, such as the East Troublesome, amid deep drought conditions, Tillotson said he’s planning to do more mitigation around the coal fires to reduce risk.

The department has traditionally cleared vegetation around the fires for 100 feet in all directions, but he is considering increasing that scope.

The fire department needs to work closely with the state Division of Reclamation, Mining and Safety to plan the mitigation because the ground over the coal seams can give way.

“I think historically that’s part of the reason we haven’t done some of the mitigation that nowadays I kind of feel like we should,” Tillotson said.

His goal this summer is for crews to work around, but not directly over, the coal seams for safety reasons. Vegetation tends to die close to the coal seam fire openings because of the heat.

State crews with the Division of Reclamation, Mining and Safety have worked at the South Canyon East mine fire to seal vents with clay material to cut off air to the coals and that’s helped. But he wants to be prepare for what could be another dry summer.

“Knowing the drought conditions we have had for the last several years and the increased fire activity we have seen the last two or three,” Tillotson said, “enhanced mitigation is probably the most effective, practical thing that we can do.”

Extinguishing a so-called “eternal” flame coal mine fire isn’t impossible, but it comes close.

“It’s certainly very difficult,” said Graves. In the history of coal mine fires in Colorado, teams have successfully extinguished one fire. In that case, the fire was burning close to the surface and workers were able to excavate the site down to the source. Often the location and depth of the fire — some of which are burning hundreds of feet underground — make such mitigation impossible.

Surface mitigation typically involves removing “fuel” in the surrounding land, sometimes cutting off vents that allow in oxygen. Water can be used to douse a coal fire that’s exposed to the surface, but not below ground.

“If you were to drill holes into the ground and actually inject water into those underground fires, it can create problems. You can actually get a steam explosion, which is a pretty significant problem,” Graves said.

Each fire is different, though, and some are located in areas where the depth and terrain have historically made all but superficial mitigation efforts impossible. Most are on private property, and on-site monitoring and mitigation requires owners’ permission.

“Our program is cooperative. We’re a voluntary program in a sense; we rely on the landowner to provide access,” Graves said.

Every five years the state evaluates coal mine fires, assessing and prioritizing them based on wildfire risk characteristics including surface temperatures, visible activity, proximity to infrastructure and the amount of fuel, largely vegetation, on the surrounding surface. The most recent evaluation and ranking was completed in 2018.

“We have a number of fires that have very limited or almost no observed surface activity, but we know there has been a fire there in the past,” Graves said.

Coal mine fires in and around the Grand Hogbacks are home to “high-priority fires,” based on proximity to infrastructure and historic activity. The Hogbacks are a rock feature resembling the scaly ridges of an alligator’s spine that extends from the Glenwood Springs through New Castle.

Graves said he’s hoping an influx of new federal funding that would more than triple his program’s current $3 million budget will help extinguish more of the state’s coal mine fires, and step up safety measures at the rest.

The state hasn’t yet applied for the money — almost $10 million per year for the next 15 years from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act — but Graves said it’s a “guaranteed distribution”; all that now stands in the way is “official guidance” about how to go about the request.

“It’s a substantial increase in funding, which is why we’re really excited about how we can put this to good work,” Graves said.

He said he hopes the money, specifically designated for coal-related activities, will allow for excavation at sites where such endeavors previously had been financially out of reach.

“Because coal mine fires are probably the biggest coal-related issue we have in Colorado, I’m expecting a majority of the funds to go toward that,” said Graves, whose department also deals with coal mine subsidence and other hazardous mine features. “We are hoping with the new funding we will make an attempt on a couple sites to possibly extinguish them and then hopefully do some larger scale projects to slow fire growth on some of the more challenging fire sites.”

Texas company awarded multimillion-dollar bid for Marshall fire debris cleanup

The money, when it comes, will allow for changes that represent an effective “paradigm shift” for his department.

Others hope the money can help change the legacy of an industry whose impact will remain long after the last fuel rock is mined.

Aimee Erickson, of the Pennsylvania-based Citizen Coal Council, called the new funding “the most important thing that has happened for coal communities in 45 years.”

“It will eliminate many dangerous abandoned coal mines,” Erickson said. “Mine fires are as bad or worse at polluting the air as coal fired powerplants. Putting out mine fires will protect the local people and their health. It will also reduce the risk of mine fires causing forest fires on the surface.”

Superior’s Larry Dorsey said he never considered the underground Marshall coal mine fire a serious wildfire threat — even though he’s well aware of the danger such fires can pose, and have, in Colorado towns that owe their very existence to coal.

In the aftermath of the disaster, he knows those “ruggedly independent” descendants of original mining residents may now struggle to rebuild on modern-day wages, at modern-day prices.

“To lose their properties and to know to replace their properties was going to cost more than they can afford is really causing some anguish,” he said.