‘It shouldn’t even exist:’ Living the sweet life in Palisade | Colorful Colorado

PALISADE • There’s an old saying here.

Mothers and grandmothers say it to their babies before they leave for college or take a job far away or otherwise feel finished with small-town life.

If you don’t take any dirt, they say, you’ll come back.

Apparently that dirt, that precious dirt rendering precious fruit, is often left behind here in western Colorado’s Grand Valley.

“A lot of people will leave, because they think they want something else,” says native Charlotte Meiners. “But then they realize this is what they want.”

They want something that’s hard to describe. It’s something that can’t be described as much as felt around Palisade.

It’s something that can only be understood by looking around the quiet, leafy square, where the birds chirp and the fruit stands greet the visitor along with a man who waves and smiles and observes, “It’s a beautiful day to a be alive.”

It’s something about this river-laced town framed by DeBeque Canyon and the Book Cliffs, this idyllic, sweet-smelling slice of Mayberry best admired in the morning light, when the big sky blushes and that river glows with those rock faces and those fuzzy, orange orbs spotting the all-encompassing orchards.

That’s what people miss when they leave. They miss the peaches.

“When I lived in the South,” says another returned native, Jamie Somerville, “I ate peaches from Georgia and South Carolina, and I’m like, ‘How does anybody eat this stuff?’”

Just as there are sayings about the dirt, there are legends about it. The dirt is said to be blessed. Blessed by the desert’s daytime heat, followed by the cool nights, and sweetened by the breeze that DeBeque Canyon sends. “The million-dollar breeze,” the first growers of the early 1900s came to call it. (Many came from Iowa, simultaneously planting the Midwest charm here).

A mysticism, indeed, hovers over this side of the valley.

How to describe it?

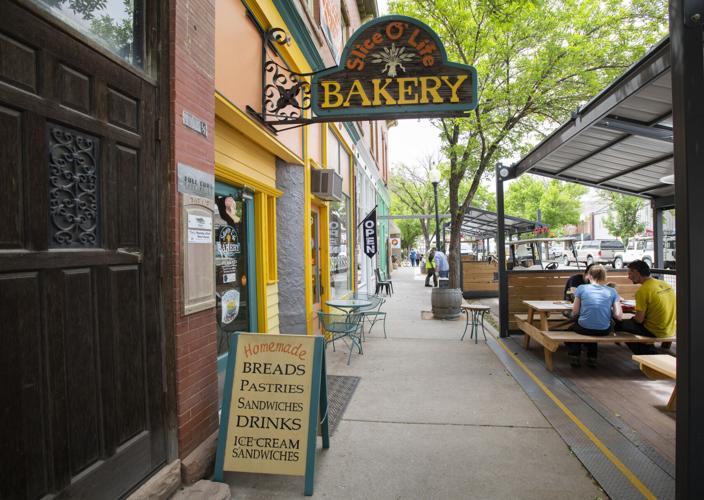

“Paradise,” says Mary Lincoln, the 72-year-old baking her bread at Slice O Life Bakery. “Like a Garden of Eden.”

Like a dream, Somerville offers.

“It shouldn’t even exist,” he says. “The trees. In the middle of the desert, you have these peach forests everywhere you look. … It shouldn’t exist. It’s all based on irrigation stuff done 100 years ago by people with a ton of foresight.”

Those first growers hauled water from the river before digging a grid of canals. That set Palisade on its definitive, economic course and established its nationwide reputation. President William Howard Taft was among attendees of the 1909 Palisade Peach Festival, the annual celebration returning this August.

Helping to set the peach standard was James Clark. His great-great grandson, Dennis Clark, has continued to tend the family orchard, in recent years claiming to prefer plowing by draft horse, like the men in the family before him, rather than by machine.

That’s the kind of sentimentality that stays with people, like the dream of the valley itself. Dennis Clark went off to college in the 1970s before being called back to the farm. “Things were struggling here,” he recalled. “So I stepped up and never did finish” the degree.

Clark is among the faithful people here — faithful to family and God, praying always that the land stays blessed, that the crop-killing evils of drought, freeze and blight stay at bay. These are a hopeful people. A peace-seeking but hard-working people.

“It’s not for the weak,” says Meiners, representing another generation of fruit growers.

She also runs the family shop of flowers. John Denver’s “Sunshine on my Shoulders” plays on the radio this morning while another mother works beside her, Caitlin van Loon.

Van Loon moved to town after 10 years in Denver. Ten years of firefighting and emergency response, and that was enough.

“This is the happy side, right?” van Loon asks her 3-year-old girl, trimming flowers beside her. “This is the happy side.”

The side, she found, where neighbors brought over eggs from their backyards. Where people asked how you were and really meant it. Where the craziness of the city felt far away. Where even the trappings of the city were rejected — the proposed Subway, for example, and the idea of apartments.

Maybe the buildings don’t change, but everything inside does.

There’s the old railroad depot, now home to a distillery and brewery. There’s the old grocery, now home to elevated cuisine to match the ever-booming wine scene here; the vineyards, too, are blessed.

There’s an old saloon, now home to the bike shop. Inside is the goateed owner, Rondo Buecheler, voicing his familiar sell: “This is the only spot in the world where you can hop on a bike and hit 25 wineries in roughly 25 miles.”

When Buecheler opened the shop 14 years ago, the fruit and wine tours “saved us,” he says. Mountain biking here wasn’t as quick to take off as on the other side of the valley, in Fruita. That’s changing in a big way after last year’s highly anticipated debut of the Palisade Plunge, a destination trail dropping from the Grand Mesa into town.

Agritourism has ruled in Palisade, but now attempts to diversify come with the marketing of that trail and others around town, not to mention the river rafting and skiing at nearby Powderhorn Resort.

“Most of the new people enjoy it — that’s why they moved here,” Buecheler says of the shift. “But not everybody’s happy with it, because it does bring in more people.”

That’s necessary, according to the mayor.

“There are people that don’t want to see growth, that want to keep the status quo,” Greg Mikolai says. “Yet, I don’t think people understand … Having grown up in a small farming community, I saw that if you don’t grow, you die.”

Palisade is different from that small farming community he knew in Minnesota.

“Palisade is a small town that I feel almost has large aspirations,” Mikolai says. “We want to keep that small-town feel, but we want to be a vibrant community.”

Vibrant and aspirational as the grapes that Kaibab Sauvage grows.

“You guys ever heard of Teroldego?” he asks beside barrels of a deep-red concoction stocked at his namesake winery, Sauvage Spectrum. “It’s grown at the base of the Dolomites in Italy, at a place where they speak German.”

It’s but one example of Sauvage’s ambitious quest for grapes suited for these winters. He knows these winters well, having grown up here.

“A lot of churches, not much to do,” he says of his childhood Palisade. “It’s changed a lot, and for the better. There’s just been a young surge of people doing creative things.”

But housing those people is a mounting problem. Palisade is not immune to the plague around Colorado born by second homebuying and investor speculation that’s driving up real estate. As in elsewhere, nostalgia here stands in the way of what some see to be necessary building.

“We have all this ag land, and we have all this opportunity to develop it, and we’re trying to balance what we call smart growth,” says Somerville, on the town’s Board of Trustees.

It would be hard to see those orchards gone, those scenes of hide-and-seek games of his youth. But this is not the Palisade he knew as a kid, he says. Not the “Huckleberry Finn life,” as some reminisce.

“It’s a lot busier,” Meiners says.

Still, it’s the place she wants to raise her daughter.

“I want my daughter to have a great feeling of growing up in, I don’t know, a not-so-crazy world,” she says.

Maybe her daughter will leave someday. Maybe she’ll take some dirt with her. Or maybe she won’t. And maybe it won’t matter.

Always, the dream of home emerges.