Backers launch campaign to set aside $300 million a year in TABOR funds for affordable housing

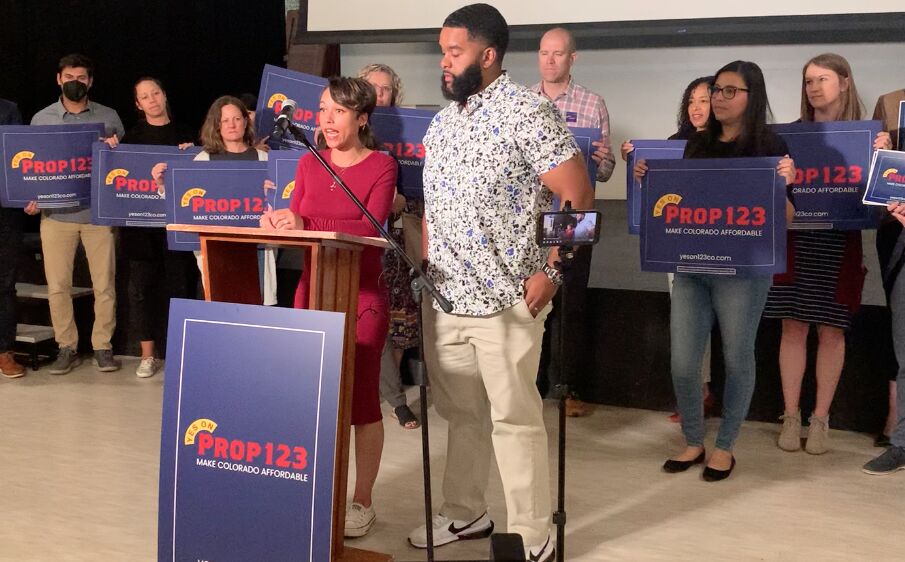

Jordan and Jojo McDonald, who expect a baby in January, hope to find a home before she arrives, but they say the high cost of housing stands in the way. They speak about their struggles at the campaign kickoff for Proposition 123 on Sept. 13.

By MARIANNE GOODLAND marianne.goodland@coloradopolitics.com

Jordan and Jojo McDonald both have good jobs – she’s a Medicaid care coordinator and he’s a teacher.

In January, the couple, who live in a two-bedroom apartment in Park, although both work in Aurora, is expecting their first daughter.

They have been pre-approved for a home mortgage, but they were told last year to “try again later” to find a home they can afford.

“It’s discouraging. We don’t know when ‘later’ is going to be,” Jordan McDonald said.

For now, they’re paying $2,300 a month for their Parker apartment. By 2032, that rent could reach $2,700 per month and a renter would need an income of $106,000 per year to afford it.

The McDonalds aren’t the only ones struggling. Homes, particularly in metro Denver, have become more and more unaffordable.

That’s where the McDonalds and more than a hundred businesses, nonprofits and elected officials hope Proposition 123 will help.

The ballot measure, previously known as Initiative 108, asks voters to set aside about $300 million annually in TABOR refunds to pay for a slate of affordable housing initiatives, which local governments will primarily handle. Backers expect 170,000 new affordable homes and rental units to be built over the next 20 years under the measure, but they also noted the current shortfall already stands at 200,000 units.

During a news conference on Tuesday, Mayor Jackie Millet of Lone Tree said her two children have just graduated college, and buying a home in today – or tomorrow’s – housing market is out of reach for them.

By 2032, the median single-family home price could reach $1.7 million, Millet said.

“That is a bridge too far,” she said. “They’ll never be able to afford a home.”

She added that the housing crisis is decimating Colorado’s middle class and making it increasingly difficult for businesses to attract and retain a workforce.

“Do we want to live in a community where nurses, city employees, managers at restaurants” or retail employees can’t afford to rent? she asked.

It’s not just an urban problem, noting Coloradans who live in rural areas face the same high cost and lack of housing.

In Eagle County, the superintendent of schools sent an email to parents, asking if anyone had “a couch” for a teacher, said Mike Johnson, president of the nonprofit foundation Gary Community Ventures, which put $2 million into the effort to get Proposition 123 on the November ballot.

“Colorado has shifted from a place of opportunity to a place where people struggle to get by,” added Gail Klapper, president of the Colorado Forum. “This is the right tool to solve the problem.”

The proposal would:

- Provide rental units with permanent deed restrictions that would limit the rental cost to 30% of household income;

- Set up a tenant equity account through the rental program that renters could use for a variety of purposes, including a down payment for a home;

- Set up an affordable housing down-payment program, with priority given to first-generation home buyers, based on income qualifications; and

- Set up a program to assist the homeless with supportive housing, rental assistance, housing vouchers and eviction defense assistance.

Local governments that accept grants from the affordable housing fund would have to meet certain requirements related to zoning and affordable housing availability, according to the measure’s fiscal analysis.

The big question is whether the money will be there to pay for it.

Johnston said budget projections determined by state economists show there will be $2 billion to $3 billion in TABOR refunds for the next few years, and he doesn’t anticipate that will go away soon. Johnston anticipates that every new dollar of economic growth will go to TABOR refunds and not to spending because the state budget can only grow by inflation plus population growth. He believes there will be at least $400 million to $500 million available every year.

“There’s no scenario that we or anyone else has modeled where you drop below $300 million per year in refunds,” Johnston said.

But revenues fall below projections for any reason, the proposition gives the legislature the ability to cut the funding in half, he said.

Proposition 123 faces no formal opposition.