‘This is how innocent people are convicted,’ defendant alleges wrongful conviction to Supreme Court

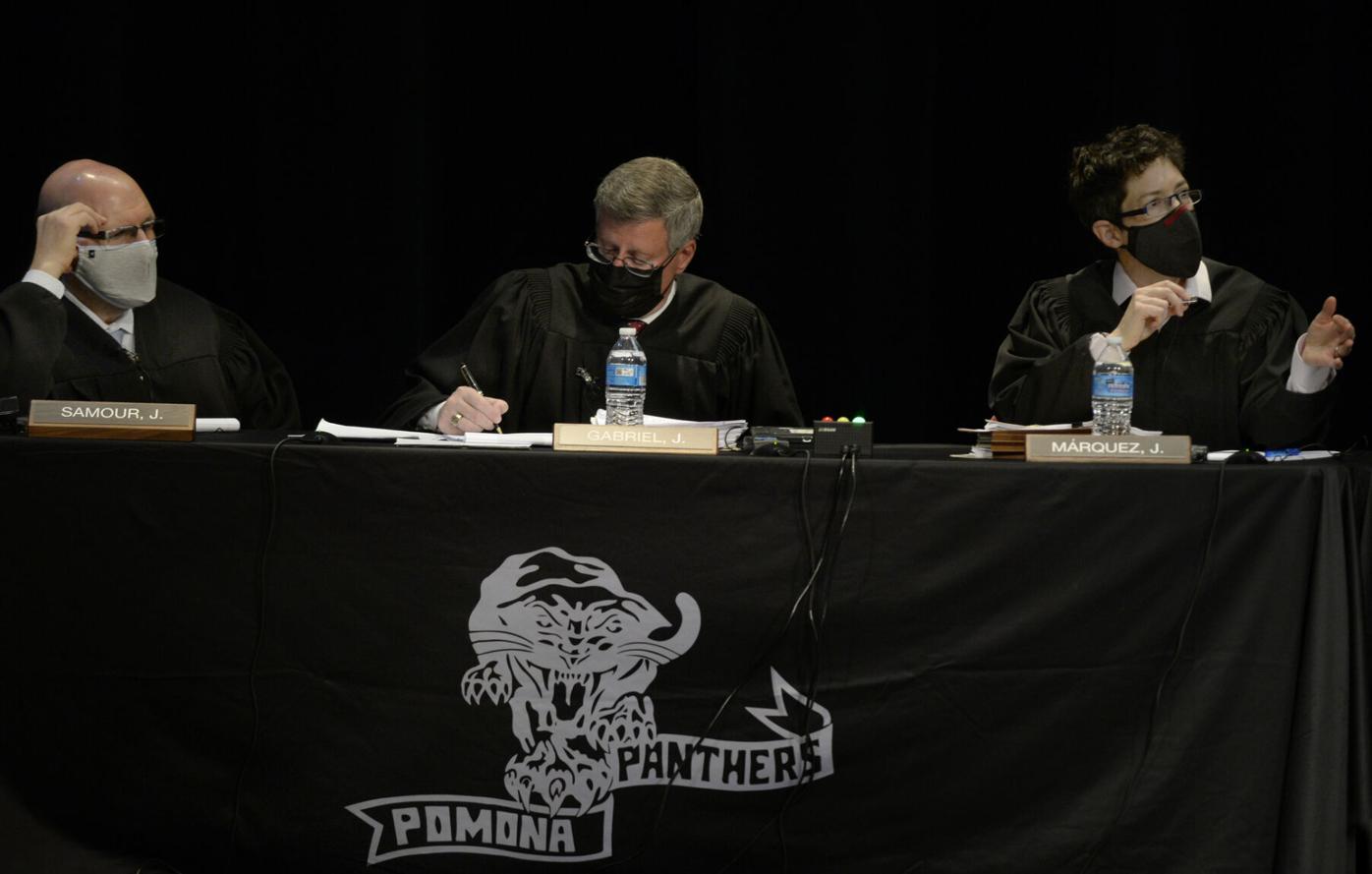

ARVADA, CO - OCTOBER 26: The Colorado Supreme Court, including left to right, justices Carlos A. Samour Jr., Richard L. Gabriel, and Monica M. Márquez, hear two cases at Pomona High School before an audience of students on October 26, 2021 in Arvada, Colorado. The visit to the high school is part of the Colorado judicial branch’s Courts in the Community outreach program. (Photo By Kathryn Scott)

Kathryn Scott

When police arrested Nora Hilda Rios-Vargas for the burglary of a Weld County trailer home where someone had stolen $15,000 in jewelry and $3,000 in coins, there was only one definitive piece of evidence linking her to the crime scene: shards of a bloody latex glove with her DNA on it.

At the same time, there were many more pieces of evidence suggesting another suspect was the actual burglar. The victim himself believed the alternate suspect was responsible. The alternate suspect knew when the victim would be gone and where he kept his valuables. Police found coins scattered outside the alternate suspect’s own trailer. The alternate suspect also had a motive to frame Rios-Vargas.

And the alternate suspect never let police question her.

However, a trial judge refused Rios-Vargas’ request to call the alternate suspect as a witness in her trial. The judge believed he was forbidden from allowing a witness to take the stand under the circumstances. Although Rios-Vargas’ jurors heard about the alternate suspect, they were never told why she did not testify.

On Tuesday, the Colorado Supreme Court heard arguments in Rios-Vargas’ appeal, after a jury convicted her as charged and she received a four-year prison sentence.

“Here, the trial court determined that Ms. Rios-Vargas had no right to call the alternate suspect, the person we claimed was actually guilty of this burglary, because that person was so apparently guilty of the crime, there was nothing we could possibly ask that wouldn’t lead to an incriminating response,” public defender Casey Mark Klekas argued to the justices.

He added: “A defendant’s rights to present a defense shouldn’t diminish the more evidence there is that someone else is guilty.”

Several members of the Supreme Court appeared visibly uncomfortable with the circumstances of Rios-Vargas’ conviction.

“It seems to me there’s a really strong argument that somebody else committed this crime,” observed Justice Richard L. Gabriel. “The prosecution successfully argued you don’t get to put this woman on. And argued all this alternative suspect evidence was speculative. Wouldn’t that suggest an unfairness?”

The government responded that Rios-Vargas had, in fact, argued to the jury she had been set up, and the defense had done everything short of placing the alternate suspect on the witness stand.

“Which would have been the most powerful piece of evidence,” pushed back Justice Monica M. Márquez.

The trailer park burglary occurred in 2013. The victim, who is now deceased, suspected the alternate suspect was the culprit. Among other circumstantial evidence, the alternate suspect rented a trailer from the victim across the street, and the burglar had coincidentally stolen the title to that home. Police never ruled out the alternate suspect as the potential burglar.

Rios-Vargas subpoenaed the alternate suspect to testify, but then-District Court Judge Thomas J. Quammen appointed an attorney for her. The attorney relayed that the alternate suspect planned to invoke her Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination.

Quammen decided he would not allow the defense to question the alternate suspect at trial, only for her to “take the Fifth.” He acknowledged there was ample evidence pointing to the alternate suspect, but her own constitutional rights were “paramount to the rights of Ms. Rios-Vargas to put on a defense.”

Last year, the state’s Court of Appeals upheld Rios-Vargas’ conviction. Although it disagreed with Quammen’s approach for handling the alternate suspect, the court nonetheless believed the Supreme Court had precluded the alternate suspect from taking the witness stand with its 1976 decision of People v. Dikeman.

In that case, a majority of justices overruled decades-old precedent and established that defendants may not call witnesses who intend to invoke their Fifth Amendment rights, only for the purpose of having the jury hear the alternate suspect decline to implicate themselves.

Now, Rios-Vargas is asking the Supreme Court to overrule Dikeman.

“This is how innocent people are convicted,” Klekas wrote to the court.

He explained the procedure that some other states have adopted, in which a trial judge determines, without the jury present, how deeply the defense may question an alternate suspect about incriminating topics. Then the suspect is permitted to take the witness stand and invoke their right against self-incrimination as needed.

“Dikeman cramped the constitutional rights of defendants and I think it’s paramount to overrule a case when it does so,” Klekas added.

Justice William W. Hood III was the most hesitant to adopt a new rule for questioning alternate suspects. He worried defense attorneys could be emboldened to place alternate suspects on the witness stand, even when there is minimal evidence to support an alternate suspect theory.

“We’re just gonna see this popping up in case after case. Maybe that sounds alarmist,” he said.

Klekas argued that if the prosecution wants the jury to know the truth about an alternate suspect, the government can simply grant immunity in exchange for the witness’s testimony. But Assistant Attorney General Brittany L. Limes believed that would disadvantage prosecutors in instances where the defendant and the alternate suspect may have actually colluded to commit the crime.

“The prosecution is put between a rock and a hard place of deciding: Do we offer this witness who might be as guilty as the defendant immunity, and essentially allow her to testify? And we cannot use her statements to prosecute her?” Limes said.

Even if that were true, responded Justice Carlos A. Samour Jr., a defendant has the constitutional right to present a defense. And in Rios-Vargas’ case, the jury was left to wonder why they never heard from the alternate suspect, if the defense was so sure she was the culprit.

“It seems to me it was unfair to the defendant to prevent them from calling their alternate suspect while at the same time (the prosecution was) arguing to the jury that the alternate suspect defense was was ambiguous and vague and speculative,” Samour said. “That seems unfair to me.”

The case is Rios-Vargas v. People.