Liberty’s torchbearers, like Oswaldo Payá, can be found the world over | Vince Bzdek

Rosa Maria Paya, left, the daughter of a prominent Cuban dissident who died in a car crash, and her mother, Ofelia Acevedo, right, talk to the media about her family’s decision to seek refuge in the U.S during a Tuesday, July 18, 2013 press conference in Miami. Paya traveled through Europe and the U.S. in April to push for an international investigation into her father’s death. Oswaldo Paya was killed in a car crash alongside another dissident in 2012.

associated press file

They are, in the words of Pulitzer-Prize winning author David Hoffman, “dreamers who dared to wish for more.”

They are people like Volodymyr Zelensky, president of Ukraine. Or Alexei Navalny, imprisoned opposition leader and freedom fighter in Russia. Or Mahsa Amini, the young woman whose death in Iran is fueling mass protests against the hijab laws. Or Tank Man, the unidentified Chinese man who faced down a column of tanks in Tiananmen Square.

They are sometimes relatively unknown to us here in America, like Oswaldo Payá, a dissident who dared to defy Fidel Castro in Cuba, inspiring thousands of Cubans to fight for democracy.

They are liberty’s torchbearers, intrepid souls who are lighting flames of freedom all over the world, and sometimes across multiple generations, refusing to let the dream of democracy die.

“I think there are people like Payá in these places, people with incredible endurance and principle,” Hoffman told me. “They are not often in the headlines, but they are there.”

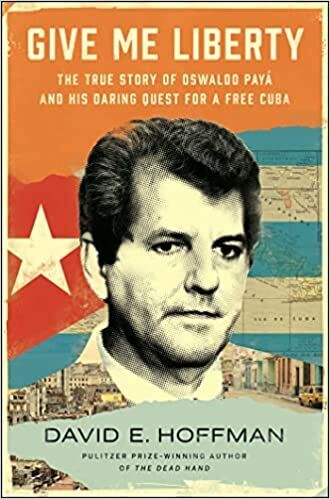

Hoffman, a longtime editor and reporter for The Washington Post, was in town at the Tattered Cover over the weekend to talk about his new book, “Give Me Liberty: The True Story of Oswaldo Payá and his Daring Quest for a Free Cuba.”

Payá formed a pro-democracy movement in Cuba in the 1990s. “A devoted Catholic, he championed a simple, bedrock belief that rights are bestowed by God, and not the state,” Hoffman writes. “Every day, he witnessed these rights trampled in Cuba. He could not stay silent.”

In 1998, in the twilight of Castro’s rule, Payá launched the Varela Project, challenging Castro’s dictatorship with an unprecedented nationwide citizen petition demanding democratic reforms such as free speech and free association. The petition was perfectly legal, allowed by a little-known clause in the constitution that Payá exploited.

Payá and his fellow liberty lovers secretly collected 11,020 signatures door to door, then surprised Castro by submitting them with great fanfare to the National Assembly in 2002. They added 14,384 signatures the following year, and nuns kept 10,000 more signatures secretly hidden. All told, more than 35,000 Cubans had signed the petition.

But Payá and his movement paid a heavy price. Castro responded by ignoring the petition, arresting dozens of Payá’s followers and sending them to prison for many years.

After receiving multiple death threats, Payá was killed in a suspicious car wreck on a remote country road, a martyrdom chillingly recounted in the opening pages of Hoffman’s book.

Payá’s dream of democracy did not die with him, however. Just as he inherited his thirst for liberty from Félix Varela, a 19th-century priest and philosopher who was Cuba’s most illustrious educator, so he passed it along to activists and protesters to come.

As recently as July 11, 2021, protesters inspired by Payá took to the streets in a massive demonstration. The ourpouring was sparked by a Facebook live video, and there are still small and local protests reverberating to this day.

Hoffman believes it’s only a matter of time until Cuba is free.

“I think Cubans lost their fear long ago — it is one of Oswaldo’s legacies,” Hoffman told me.

“Cuba today resembles the Soviet Union in 1983 — it is showing signs of deep stagnation,” added the former Moscow correspondent.

“There are severe food shortages; electricity blackouts; the country that once produced one quarter of all the world’s sugar now barely produces enough to satisfy its own needs. So conditions are dire. This is one precondition for change. The other is that the Cuban people have to demand change, as they did on July 11, 2021. I think the popular desire for change is now stronger than it has been at any time during the last 64 years. At some point it will break through.”

Hoffman’s story of Payá’s journey tries to answer larger questions about the innate quest for liberty.

“How do people gain the right to think and speak freely, advocate their views, follow their conscience, worship or assemble as they desire without persecution?” Hoffman asks. “How do they secure the right to choose their leaders and set the course for their own future? What does it take to attain such freedoms?”

Hoffman said he tends to be an optimist about the democratic future. “Just ask anyone who has lived for a few years under a true dictatorship — anyone who has come up against jail time for shouting something in the street, or who has struggled with bread lines or who has been targeted by the secret police for a tweet — if they like it. Given a chance, people flee them. Open societies and democracy are more resilient because they are able to self-correct, adapt and enjoy legitimacy.”

Interestingly, just as I was talking to Hoffman, Freedom House released a new report that shows, after many years of stagnation and backtracking, democracy is on the march again.

This year’s “Freedom in the World” survey notes that the number of countries suffering democracy declines in 2022 was the lowest in 17 years, and was nearly matched by the number of countries experiencing improvements.

“If five decades of global monitoring tell us anything, it is that the demand for fundamental rights is universal and impossible to extinguish,” the report’s authors wrote. “Pro-democracy movements have arisen again and again in some of the world’s most repressive environments.”

Hoffman is realistic about a looming global contest between democracy and dictatorship that did not exist 15 years ago. “Something has changed, and we are in for a new struggle,” he said. But he sees the same kind of long-term hope Freedom House does.

“Oswaldo Payá showed,” Hoffman writes, “that no state, no matter how dictatorial, can imprison an idea forever. The quest for liberty runs free.”

Vince Bzdek, executive editor of the Denver Gazette, Colorado Springs Gazette and Colorado Politics, writes a weekly news column that appears on Sunday.