The gifts and curses of Denver’s historic Fairmount Cemetery

DENVER • Kendra Briggs, president and CEO of Fairmount Cemetery, is driving on the pavement until it turns to dirt. The road exits the historic place of marble markers and monuments and manicured grass and trees and enters a much different place.

It’s an off-limits place of weeds and tangled, twisting timber. It’s a blank canvas waiting to be realized.

Briggs calls it the “back 40,” for the acreage’s place behind the proper development spanning about 280 acres. She gets out of her car to wander through the thicket.

“This is where a lot of the wildlife likes to hang out,” she says.

The wildlife — the songbirds and raptors, the deer and occasional fox, bobcat and coyote — are responsible for the latest intrigue on a long list of intrigues here at one of Colorado’s oldest cemeteries. The National Wildlife Federation recently certified Fairmount Cemetery as a protected habitat.

A coyote lies between gravestones on Wednesday, March 29, 2023 at Fairmount Funeral Home, Cemetery & Crematory in Denver, Colo. (Timothy Hurst/Denver Gazette)

Timothy Hurst/Denver Gazette

A coyote lies between gravestones on Wednesday, March 29, 2023 at Fairmount Funeral Home, Cemetery & Crematory in Denver, Colo. (Timothy Hurst/Denver Gazette)

So Briggs and fellow executives can point to another feather in their cap. Others: a canopy of a size and variety hardly matched across Denver; a stained glass collection said to be unmatched across all of Colorado; and a claim to one of North America’s largest gardens of heirloom roses, with 300-plus bushes popping with all sorts of reds, whites, pinks and purples from the vision of a landscaper more than a century ago.

“I’m a photographer, so I always have my camera with me,” says Robin Brilz.

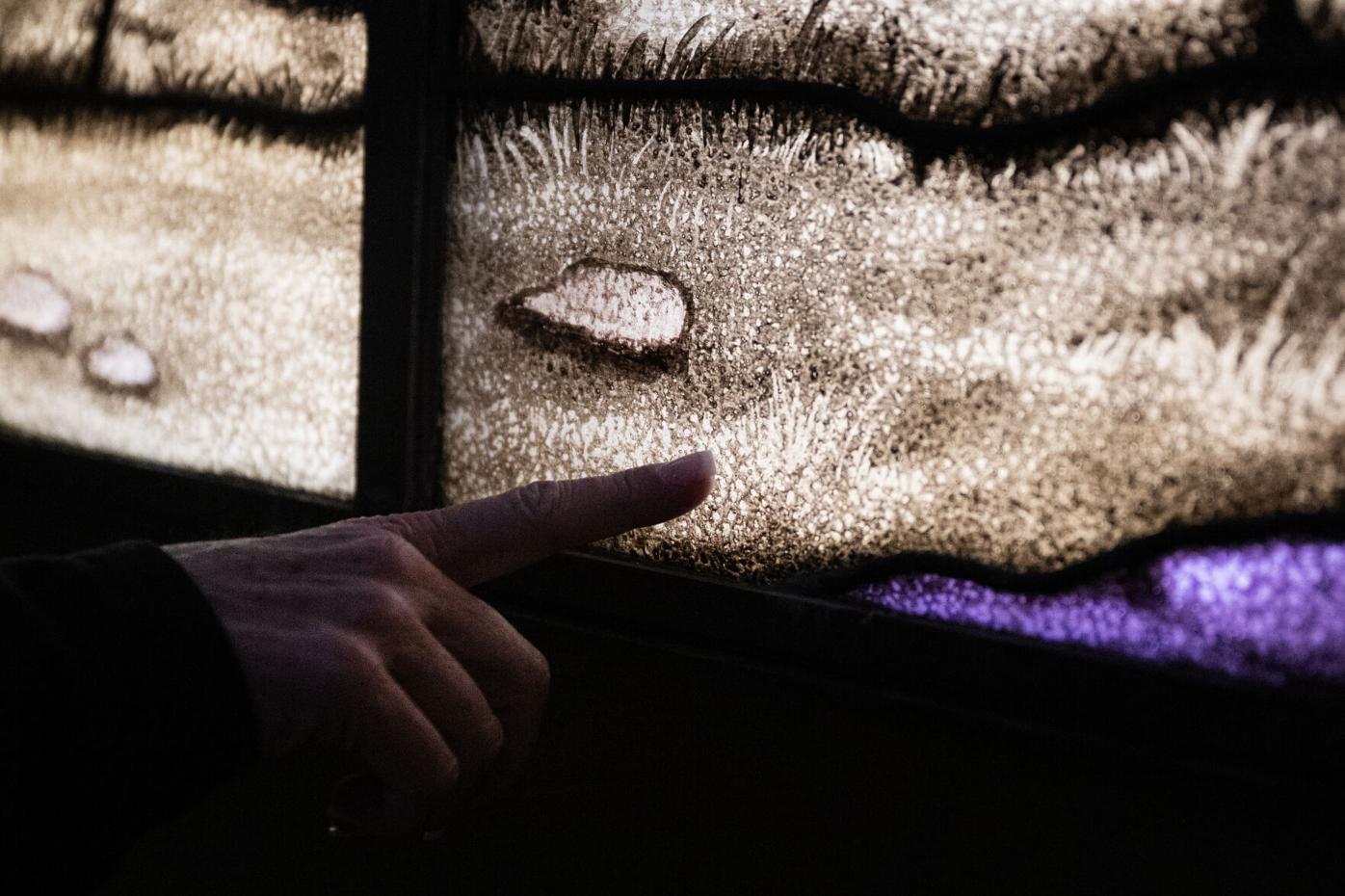

Fairmount Heritage Foundation director Robin Brilz inspects the detailed paintwork on a stained glass window interpretation of French painter Jean-François Millet’s painting “The Gleaners,” one of the many stained glass windows in the mausoleum on Wednesday, March 29, 2023 at Fairmount Funeral Home, Cemetery & Crematory in Denver, Colo. (Timothy Hurst/Denver Gazette)

Timothy Hurst/Denver Gazette

Fairmount Heritage Foundation director Robin Brilz inspects the detailed paintwork on a stained glass window interpretation of French painter Jean-François Millet’s painting “The Gleaners,” one of the many stained glass windows in the mausoleum on Wednesday, March 29, 2023 at Fairmount Funeral Home, Cemetery & Crematory in Denver, Colo. (Timothy Hurst/Denver Gazette)

She frequents the cemetery as director of the Fairmount Heritage Foundation. That’s the historical and cultural stewarding fund overseeing both of Denver’s longest-going cemeteries: Fairmount, which dates to 1890, and Riverside, which was established earlier in 1873.

Their stories of triumph and tribulation are captured in the book “Fairmount and Historic Colorado,” by David Fridtjof Halaas. The book was published in 1976, but the experience at the properties is still true to the author’s words: “to take a stroll through the grounds of Fairmount and Riverside and to observe the names inscribed on the monuments is to take a journey through Colorado’s early history.”

Sunlight beams in through stained glass windows as Fairmount Heritage Foundation director Robin Brilz, left, and volunteer tour guide Tom Morton walk through the nave of the Little Ivy Chapel at Fairmount Cemetery.

Timothy Hurst/Denver Gazette

Sunlight beams in through stained glass windows as Fairmount Heritage Foundation director Robin Brilz, left, and volunteer tour guide Tom Morton walk through the nave of the Little Ivy Chapel at Fairmount Cemetery.

Timothy Hurst/Denver Gazette

Sunlight beams in through stained glass windows as Fairmount Heritage Foundation director Robin Brilz, left, and volunteer tour guide Tom Morton walk through the nave of the Little Ivy Chapel at Fairmount Cemetery.

At Fairmount, they are names that might ring a bell: Boettcher, of the philanthropic family; Byers of the pioneering Rocky Mountain News; Tabor of mining fame; Moffat of railroading fame; Vail of highway fame.

“There’s George Lipe,” says Tom Morton, one of the cemetery’s longtime tour guides, strolling past graves along Millionaires Row. “He designed the railroad through the Royal Gorge.”

Morton walks excitedly, pointing this way and that. “This is Henry Cordes Brown. He built the Brown Palace Hotel. … That’s Walt Cheesman. …”

Tom Morton, a volunteer with the Fairmount Heritage Foundation, pauses to talk about the family plot for William Byers, the founder of the Rocky Mountain News, Colorado’s first newspaper, while touring a section of Farmount Cemetery referred to as “Millionaires Row.”

photos by Timothy Hurst, THE Gazette

Tom Morton, a volunteer with the Fairmount Heritage Foundation, pauses to talk about the family plot for William Byers, the founder of the Rocky Mountain News, Colorado’s first newspaper, while touring a section of Farmount Cemetery referred to as “Millionaires Row.”

Brilz says it’s easy for her to go down the “rabbit hole.” She’ll see a name, familiar or not, drawn perhaps by the intricate, hand-cut design of their gravestones, “and the next thing you know, I’m spending six or eight hours researching who they were and what they did for Colorado and Denver,” she says.

As for Briggs, she likes to go to a place behind it all, a place seemingly far away. The “back 40” seems to represent nothing and everything all at once — in some ways hinting at an uncertain future at Fairmount.

‘Sought-after patch of green’

Compared with the development in the front, Briggs sees something different for this wild swath. It was, she says, the impetus for the recent habitat certification.

“I foresee something like Colorado native grasses and native trees,” she says.

Something, she says, that might resist the plight of Fairmount proper.

All too close to the top of Briggs’ mind is the fate of Riverside, which lost its water rights in 2001. Burials stopped in 2005. “Which is why (Fairmount and Riverside) look so different,” Briggs says.

Fairmount is supported by wells and Windsor Lake, but that supply is increasingly strained and limited. No longer of use is the historic High Line Canal gone dry. The cemetery’s early organizers saw that as their great advantage to beautifying the land in the likes of stately grounds back East — grounds for the frontier’s pioneers to match those for America’s first patriots.

“When I started (here) in 1998,” Briggs says, “we had the High Line Canal, we had all the water we wanted. It was lush. Now we can only pump so much. It’s hard to explain to people why it’s not as green as it was before.”

Green was always a bold, ambitious vision. For the men who planned Riverside and later Fairmount, verdant scenery was paramount.

A beautiful, tranquil place for the dead and the bereaved was as central to Denver’s developing civilization as schools, churches and theaters, the historian Robert Athearn wrote in his introduction to “Fairmount and Historic Colorado.”

A small lake sits in the back undeveloped acres of the cemetery on Wednesday, March 29, 2023 at Fairmount Funeral Home, Cemetery & Crematory in Denver, Colo. The back area is all private property and isn’t accessible to the public, but serves as an important habitat for wildlife in Denver. (Timothy Hurst/Denver Gazette)

Timothy Hurst/Denver Gazette

A small lake sits in the back undeveloped acres of the cemetery on Wednesday, March 29, 2023 at Fairmount Funeral Home, Cemetery & Crematory in Denver, Colo. The back area is all private property and isn’t accessible to the public, but serves as an important habitat for wildlife in Denver. (Timothy Hurst/Denver Gazette)

A dignified cemetery here would be “the much sought-after patch of green at the edge of the fabled Great American Desert,” Athearn wrote. It would be “the suggestion that residents of youthful Denver had not left behind their sense of propriety, (their) good taste and their solemn regard for family and friends since departed.”

The book’s author, Halaas, traces first attempts to the treasurer of the Denver City Town Co. William Larimer eyed a hillside called Mount Prospect — “aware, however,” Halaas wrote, that the parcel “properly belonged to the Arapahoe Indians.”

Larimer and influential others got their way in 1860. That was only for the cemetery to be doomed in the middle of what was a raucous, violent year around town. Mount Prospect became the resting place for hanged outlaws, giving the property a seedy reputation.

After the fanfare that accompanied its 1876 debut, Riverside Cemetery eventually fell out of favor as well.

The name spoke to founders’ optimism in the South Platte River giving life to their greenery. A Rocky Mountain News reporter in 1879 disapproved: “The naked prairie, treeless and almost verdureless … would seem to present about as hopeless a basis for an attractive cemetery as one could well imagine.”

While operators vied for water, the Burlington Railroad went on to run “uncomfortably close” to the hallowed grounds, Halaas wrote. With the added prospect of Denver’s growth, company men including Henry Teller and Harper Orahood — major figures in mining booms in the mountains — saw an opportunity to build what they called Fairmount Cemetery.

They brought in an architect named Wendell to design expensive edifices that would proudly proclaim the property in 1890: the Gate Lodge of Richardsonian arches and pillars and the Gothic dream of what would be known as Ivy Chapel. Later came the Fairmount Mausoleum, the gleaming-white, two-story monolith perfected with a vibrant array of stained glass.

Tom Morton, a volunteer with the Fairmount Heritage Foundation, walks down the nave of the Little Ivy Church at Fairmount Cemetery in Denver.

photos by Timothy Hurst, THE Gazette

Tom Morton, a volunteer with the Fairmount Heritage Foundation, walks down the nave of the Little Ivy Church at Fairmount Cemetery in Denver.

Another hired man in Fairmount’s early days was Rienhard Schuetze, a well-educated landscape architect from Germany. Along with all of those rose bushes, he got busy planting, according to cemetery history, more than 4,000 trees.

Nature and nurture

Many of the trees were non-natives — sycamores, maples, buckeyes, elms. They were parts of an eye-popping layout that caught the admiration of city officials. Schuetze was tapped to be Denver’s first landscape architect, going on to cement his legacy with City Park. It was centerpieced by a lake intended to be aesthetic and pragmatic for irrigation.

A placard is attached to a swamp white oak tree, one of the cemetery’s “Champion Trees,” on Wednesday, March 29, 2023 at Fairmount Funeral Home, Cemetery & Crematory in Denver, Colo. (Timothy Hurst/Denver Gazette)

Timothy Hurst/Denver Gazette

A placard is attached to a swamp white oak tree, one of the cemetery’s “Champion Trees,” on Wednesday, March 29, 2023 at Fairmount Funeral Home, Cemetery & Crematory in Denver, Colo. (Timothy Hurst/Denver Gazette)

Now in this water-strapped day at Fairmount, one wonders about Schuetze’s legacy. One wonders, too, about Wendell’s creations.

“It would be very sad to lose this,” Brilz, of the heritage foundation, says inside the chapel.

The mastic sealant, once put on the building to help protect it, peals back from the Little Ivy Chapel on Wednesday, March 29, 2023 at Fairmount Funeral Home, Cemetery & Crematory in Denver, Colo. (Timothy Hurst/Denver Gazette)

Timothy Hurst/Denver Gazette

The mastic sealant, once put on the building to help protect it, peals back from the Little Ivy Chapel on Wednesday, March 29, 2023 at Fairmount Funeral Home, Cemetery & Crematory in Denver, Colo. (Timothy Hurst/Denver Gazette)

Chairs sit in the side aisles of the Little Ivy Chapel, which once stored the deceased in winter before graves could be dug in the frozen soil of Fairmount Cemetery.

Timothy Hurst/Denver Gazette

Chairs sit in the side aisles of the Little Ivy Chapel, which once stored the deceased in winter before graves could be dug in the frozen soil of Fairmount Cemetery.

That’s the risk, decades after ill-advised ivy removal led to today’s peeling, crumbling stone.

Not long ago, Briggs says there was a grant opportunity to restore the chapel and the Gate Lodge. The cemetery, which operates as a nonprofit, struggled to come up with required matching dollars, Briggs says. “We just don’t have the funds.”

Sunlight beams in through stained glass windows as Fairmount Heritage Foundation director Robin Brilz, left, and volunteer tour guide Tom Morton walk through the nave of the Little Ivy Chapel at Fairmount Cemetery.

Fairmount Heritage Foundation director Robin Brilz inspects the detailed paintwork on a stained glass window in the mausoleum at Fairmount Cemetery.

Timothy Hurst/Denver Gazette

Fairmount Heritage Foundation director Robin Brilz inspects the detailed paintwork on a stained glass window in the mausoleum at Fairmount Cemetery.

Fairmount Heritage Foundation director Robin Brilz inspects the detailed paintwork on a stained glass window interpretation of French painter Jean-François Millet’s painting “The Gleaners” in the mausoleum at Fairmount Cemetery.

Timothy Hurst/Denver Gazette

Fairmount Heritage Foundation director Robin Brilz inspects the detailed paintwork on a stained glass window interpretation of French painter Jean-François Millet’s painting “The Gleaners” in the mausoleum at Fairmount Cemetery.

She says the water outlook and the costs attached to it complicate the funding picture. Still, Fairmount is in demand. Briggs says about 500 people are buried or cremated here every year — many, she says, seeking to join a long, proud history.

Tom Morton, a volunteer with the Fairmount Heritage Foundation, pauses to talk about the mausoleums found in a section of the cemetery referred to as “Millionaires Row” on Wednesday, March 29, 2023 at Fairmount Funeral Home, Cemetery & Crematory in Denver, Colo. (Timothy Hurst/Denver Gazette)

Timothy Hurst/Denver Gazette

Tom Morton, a volunteer with the Fairmount Heritage Foundation, pauses to talk about the mausoleums found in a section of the cemetery referred to as “Millionaires Row” on Wednesday, March 29, 2023 at Fairmount Funeral Home, Cemetery & Crematory in Denver, Colo. (Timothy Hurst/Denver Gazette)

It’s far from just Millionaires Row. Just as Fairmount is the final resting place for senators and mayors and doctors and lawyers, it is also for farmers and teachers and artists and carpenters. Here lies a cattleman. Here a gambler. Here a soldier.

Here’s Mabel Costigan, the first president of the League of Women Voters. Here’s Justina Ford, the state’s first Black woman who worked as a licensed physician. Here’s Hyman Zadek Salomon, listed as Denver’s first Jewish settler.

“Here too can be seen the lesser known names,” Halaas noted in his book.

“Men and women who each in their individual ways contributed to make Denver and Colorado what it is today.”

And they all deserve the beautiful cemetery first envisioned here, Briggs says. Maybe that’s green. Maybe that’s something else.

“There was an old advertisement for Fairmount that called it the Silent City of Peace,” Briggs says. “Where else can you go inside Denver and actually meditate and be somewhere quiet and feel like you’re not in the city at all?”

How to continue that? She ponders that wandering through the “back 40.”

She passes the dry canal. The old buildings for pumping and irrigating.

Fairmount Funeral Home, Cemetery & Crematory President and CEO Kendra Briggs walks in the back undeveloped acres of the cemetery on Wednesday, March 29, 2023 at Fairmount Funeral Home, Cemetery & Crematory in Denver, Colo. The back area is all private property and isn’t accessible to the public, but serves as an important habitat for wildlife in Denver. (Timothy Hurst/Denver Gazette)

Timothy Hurst/Denver Gazette

Fairmount Funeral Home, Cemetery & Crematory President and CEO Kendra Briggs walks in the back undeveloped acres of the cemetery on Wednesday, March 29, 2023 at Fairmount Funeral Home, Cemetery & Crematory in Denver, Colo. The back area is all private property and isn’t accessible to the public, but serves as an important habitat for wildlife in Denver. (Timothy Hurst/Denver Gazette)

She passes birds singing in the trees and scrounging in the dirt. She passes a goose carcass, the apparent prey of a predator. She passed a coyote on the way in. Now she stops at a pond to watch the ducks.

“We may not have this forever,” she says.

But we should, she thinks. This is how it should be, she says. A place for the animals. A place left open and wild. Left for nature to prevail.