Canvas is half-blank for artists after Warhol’s Supreme Court copyright loss | John Moore

“Art,” Andy Warhol liked to say, “is anything you can get away with.”

Well, (Campbell’s) soup to nuts, Andy: Not always. Not even in death.

The Supreme Court handed down a controversial copyright ruling on Thursday that pits one kind of artist squarely against another: Photographers vs. artists who make art based on other people’s photographs.

That ruling was cheered by one side, sent chills down the other – and left many in the worlds of both art and commerce feeling both conflicted and thoroughly confused about what permissions artists do and do not have going forward when it comes to creative expression.

Many like Denver’s Mark Sink, a co-founder of The Museum of Contemporary Art Denver who has an uncommonly close connection to both of the major players in this case: Aspen photographer Lynn Goldsmith and the scary Andy Warhol Foundation that runs the estate of seminal pop-culture artist.

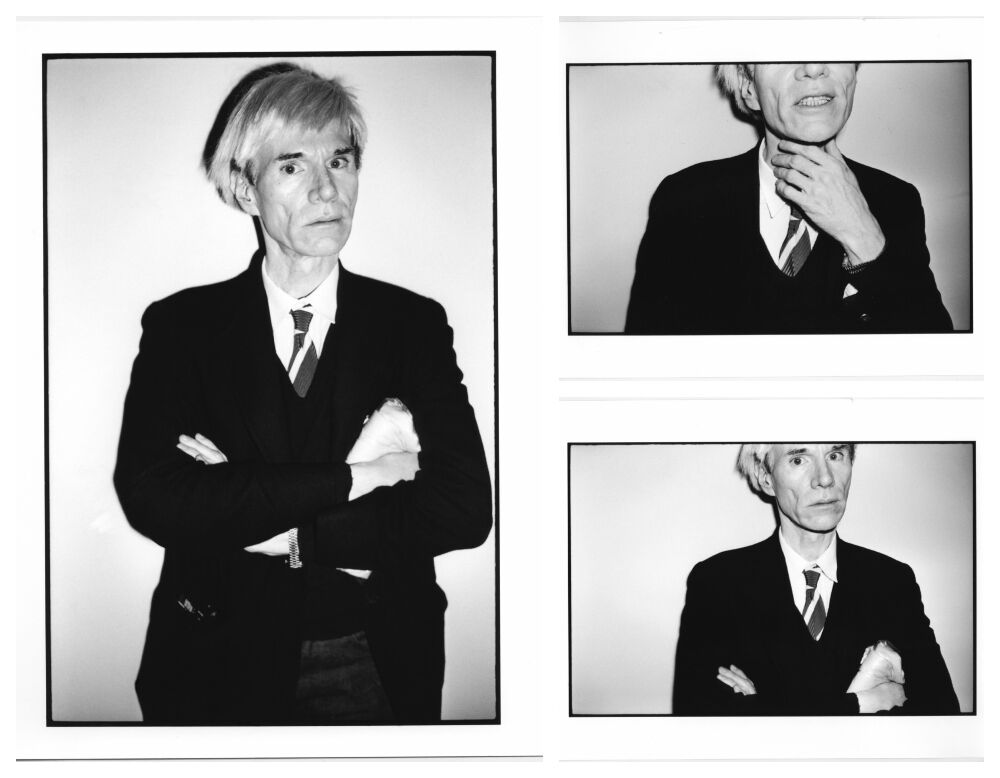

Goldsmith and Sink are longtime photography pals. Warhol and Sink were friends back in the day. Sink not only appears in many of Warhol’s seminal photographs, he took many iconic photos of Warhol himself, including the famous one of Warhol in front of a Calvin Klein underwear model. More than 30 of Sink’s photos are included in the 2022 Netflix series “The Andy Warhol Diaries.” (And, speaking of egregious copyright abuse: Sink says he was paid only about $800 for their use.)

In taking on the Warhol Foundation, “Lynn took on one of the biggest Goliaths out there,” Sink said. “They are a really powerful group of people.”

But first things first: How did Sink, a lifelong Denverite, hook up with Warhol in the first place?

“I met Andy in Fort Collins in 1981, when I was an art student and bike racer,” Sink said. “He was in town for an exhibition called ‘Warhol at Colorado State University.’ He took my phone calls and we went on several dates. He reviewed and encouraged my work, and he put me on the payroll of his Interview Magazine, which was one of my dream publications.”

Along the way, Warhol took pictures of Sink as well –” some of them with my pants down,” he said with a laugh.

Mark Sink.

Courtesy Mark Sink

Mark Sink.

Here’s what you need to know about the legal case: In 1984, Vanity Fair commissioned Warhol to create an original piece of art to serve as the cover for a profile it was preparing on Prince. Warhol used one of Goldsmith’s existing photos as a starting point, and Vanity Fair paid Goldsmith at the time to license the photo. (Which is more than can be said of Newsweek magazine, which published Goldsmith’s original photo in 1981 without her authorization, she says.) Warhol then created several images he called ”The Orange Prince” silkscreen series in his signature pop-art style. Vanity Fair ran the one of Prince with an appropriately purple face. All well and good.

That legal problems began 32 years later, following Prince’s 2016 death, when someone from the next generation of Vanity Fair editors found another image from the series in the archives and ran that one on the cover, without asking Goldsmith’s permission, or paying her for it. The typically divided Supreme Court upheld a lower-court ruling that Goldsmith’s copyright was violated by a 7-2 vote. Photographers are entitled to copyright protection, even against famous artists, Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote in her opinion.

“I fought this suit to protect not only my own rights, but the rights of all photographers and visual artists to make a living by licensing their creative work, and also to decide when, how, and even whether to exploit their creative works or license others to do so,” Goldsmith said.

But few can honestly claim to fully understand the case’s immense implications on copyright law just yet.

Photographers, of course, deserve to be compensated whenever their work is used for commercial purposes. That’s a given. But then there is “appropriation art” – a thriving genre of pop-culture art largely birthed by Warhol. That’s when an artist takes inspiration from an existing, copyrighted source – say, a photograph, a song or a Campbell’s Soup can – and transforms it into something uniquely their own, or uses it to make a larger political or artistic commentary. That’s a key legal word here: Transform.

Collin Parson, Director of Galleries and Curator for the Arvada Center and whose work proliferates from local parks to Meow Wolf Denver, has a pretty basic outlook on this: “I think just about anything can be made into art,” he said.

For 47 years, the prevailing legal opinion has been that you can borrow inspiration from another artist – you just can’t blatantly copy them or lazily rip them off. That comes from the Copyright Act of 1976, which established a cherished legal protection for artists known as “fair use.” Essentially, fair use says that a little bit of copying without the owner’s permission is OK.

This notion was reaffirmed earlier this month when pop star Ed Sheeran triumphed in a plagiarism lawsuit alleging he lifted chord progressions from Marvin Gaye’s 1973 hit “Let’s Get It On” for his 2014 song, “Thinking Out Loud.” He clearly did borrow but, the judge ruled, Sheeran’s song is enough his own.

Then there is Richard Prince, who has been under years-long legal copyright assault for his controversial practice of taking other people’s Instagram photos, slightly doctoring them and selling them for up to $100,000 each. (That is not a misprint.)

“Andy often would say, ‘Smart borrows – genius steals,” Sink said of a quote he stole from Oscar Wilde (probably).

When the Goldsmith ruling was announced, many in the art world immediately assumed it was going to blow up “fair use” once and for all. Bruce Boyden, writing for the Marquette University Law School, predicted last October that “a starkly pro-Goldsmith decision risks a whole generation of artists who will be chilled. The rich and fabulous will still be able to get licenses when they need them, but the poor and obscure won’t, and won’t be able to publish their works on social media or elsewhere without one.”

In writing the minority dissent, Justice Elena Kagan warned that the decision would “stifle creativity of every sort” and suggested the majority needed to “go back to school” for an Art History 101 refresher course.” (And that is what we call “A Supreme Court Stinger”!)

The thinking goes if the next wave of Warhols are prevented from, for example, using developing digital technologies to turn existing samples andphotographs into all kinds of newfangled art forms like NFTs, it will stop the burgeoning field of “generative art” (or “artificial intelligence art”) in its tracks. And that is a very big deal, considering that, by one estimate, generative art will be a $110 billion annual industry by 2030.

But no legal hammers are coming down on appropriation artists anytime soon. That’s because this case did not ultimately come down to a question of fair use. It came down to, surprise: Money.

Sotomayor said the Supreme Court focused on the specific fact that Warhol was commissioned to create a product for Vanity Fair for a commercial purpose. It was a business transaction that served the same purpose as Goldsmith’s original photo in Newsweek: To use Prince’s likeness to sell magazines.

That’s different from Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup cans, Sotomayor argued, “because the soup-cans series uses Campbell’s copyrighted work for an artistic commentary on consumerism.” Also protected: Parody, criticism and education.

Bottom line: Vanity Fair paid for the use of one print in the series in 1984. It did not pay for the use of another print from that series in 2016.

That’s why, Sink believes, “I don’t think this is going to open any floodgates of artistic repression,” he said. “I feel like that this case falls into its own category because it was a work-for-hire situation.”

The Andy Warhol Foundation issued a statement saying it was important to note that the ruling “did not question the legality of Andy Warhol’s creation of the Prince series.”

The case is, to put it mildly, “a very complicated, double-edge sword for artists,” Sink said. But two things he’s sure of: 1. “It really is the Wild West out there now” when it comes to these quickly evolving issues. And 2. Warhol (who died in 1987) would be loooooving this.

“One way or the other, Andy just keeps reaching out of the grave,” Sink said with a laugh.

“This case is putting appropriation art on the map and on the front pages like never before,” Sink said, just like when Jesse Helms’ public campaign against Robert Mapplethorpe only served to make the controversial photographer more famous than he ever would have been otherwise. The best thing, Sink said, “is that this case has brought an important philosophical discussion of photography and art to many people around the world.”

Whatever comes next, Parson said: “Artists have always made our own paths – and I think that will continue to be true.”

And then there is this, from Chicago attorney and Denver native Daniel Lynch: “My hot on all of this? What a fantastic decision this is for lawyers!” he said with a laugh.

John Moore is the Denver Gazette’s Senior Arts Journalist. Email him at john.moore@denvergazette.com