A decade later, mitigation against new Black Forest inferno remains incomplete

RnJhbmNlcyBCdXJrZSwgd2hvIGJ1aWx0IGhlciBmaXJzdCBob3VzZSBpbiBCbGFjayBGb3Jlc3QgNTUgeWVhcnMgYWdvLCB0YWtlcyBoZXIgZG9nLCBCZWxsYSwgZm9yIGEgbW9ybmluZyB3YWxrIHRocm91Z2ggdGhlIHRyZWUtbGVzcyBuZWlnaGJvcmhvb2QgYWxvbmcgV2lsZCBPYWsgRHJpdmUuIEJ1cmtlIGdhdGhlcmVkIGhlciB0d28gZG9ncywgdGhyZWUgY2F0cyBhbmQgYXJ0d29yayB3aGVuIHNoZSBldmFjdWF0ZWQgSnVuZSAxMSwgMjAxMywgaW4gdGhlIGVhcmx5IGhvdXJzIG9mIHRoZSBCbGFjayBGb3Jlc3QgZmlyZS4gU2hlIGxvc3QgZXZlcnl0aGluZyBzaGUgbGVmdCBiZWhpbmQsIGJ1dCByZWJ1aWx0IGFuZCBtb3ZlZCBpbnRvIGhlciBuZXcgaG9tZSB3aXRoaW4gYSB5ZWFyIG9mIHRoZSBmaXJlIHRoYXQgZGVzdHJveWVkIDQ4OSBob21lcy4=

Q2hyaXN0aWFuIE11cmRvY2ssIFRoZSBHYXpldHRl

As fire erupted in a densely wooded bedroom community northeast of Colorado Springs on June 11, 2013, Laura Lollar was driving home from a working lunch where the lead communications officer for the 2012 Waldo Canyon fire talked about handling unexpected challenges.

The coincidence for Lollar, of seeing fire in the treetops lining Shoup Road as she neared her driveway in Black Forest, was a moment of note.

The dark irony of it came later.

“I looked at those trees burning and thought, ‘Gee, that looks bad. I hope somebody’s called that in,’” she said.

Hot, dry, “red flag” weather and high winds that summer afternoon quickly whipped what began as an isolated blaze into an inferno that over nine days burned more than 14,000 acres and 500 buildings. It was the state’s most destructive wildfire, until the 2021 Marshall fire in Boulder County.

This month, Laura Lollar holds a painting of her 1920s log cabin that was destroyed in the 2013 Black Forest fire. Lollar rebuilt on the same property along Shoup Road.

Christian Murdock, The Gazette

This month, Laura Lollar holds a painting of her 1920s log cabin that was destroyed in the 2013 Black Forest fire. Lollar rebuilt on the same property along Shoup Road.

Two people lost their lives in the Black Forest fire. Lollar lost her dream home, a 1920s log cabin originally owned by one of the area’s first schoolteachers.

Ten years later, like a number of her neighbors, she has rebuilt on the same lot.

The Black Forest she sees from her car and her porch, however, is much changed — and likely not changed enough to keep another such tragedy at bay, she said, gazing around a lot once so thick with trees she didn’t realize others lived so close.

On Thursday, Pikes Peak can be seen clearly through the burned trees still standing along Wild Oak Drive after the 2013 Black Forest fire. The trees blocked most of the view of the 14,115-foot mountain before the fire.

Christian Murdock, The Gazette

On Thursday, Pikes Peak can be seen clearly through the burned trees still standing along Wild Oak Drive after the 2013 Black Forest fire. The trees blocked most of the view of the 14,115-foot mountain before the fire.

“Most people, like us, had everything burn, so they didn’t have to do too much mitigation,” she said. “But we’re all still very conscious of it, and in a lot of ways, thankful that the trees around us burned so that we would be a little bit more secure should it come back around in the future.”

Laura Lollar holds a pot that survived the 2013 Black Forest fire. Lollar lost her 1920s log cabin in the fire and has rebuilt on the same site along Shoup Road.

Christian Murdock, The Gazette

Laura Lollar holds a pot that survived the 2013 Black Forest fire. Lollar lost her 1920s log cabin in the fire and has rebuilt on the same site along Shoup Road.

She also knows if there is another fire, mitigation only works if every neighbor is doing their part.

They are not.

“When I drive by different pieces of property, some people haven’t done anything about clearing and thinning the trees,” Lollar said. “Most of us learned that lesson pretty clearly … but there still are still people out there that didn’t.

“Or they just don’t care.”

‘A dire situation, to be honest’

A few months before the fire, the Black Forest News ran a column headlined, “Is the Handwriting on the Wall? What Can Black Forest Landowners Do?” lamenting the “sorry condition” of thick fire “fuel loads” along roads and property owners’ general low compliance with proper thinning techniques.

“Would it take a very close call in the Black Forest, with homes burning up,” went the foreboding, “or is fire mitigation just too boring?”

Some residents, like Lollar, have spent countless hours rebuilding lives and homes, cutting trees, trimming branches and hauling them away. For others, a lack of will seems to play a part in areas where ponderosa pines grow so tight the forest is in places nearly impenetrable. Elsewhere, physical or financial limitations burden landowners who would otherwise want to mitigate.

Laura Lollar looks out over her backyard on June 2, with a view of her neighbors in the distance. Lollar couldn’t see them before the 2013 Black Forest fire because of dense trees behind her orginal 1920s log cabin.

Christian Murdock, The Gazette

Laura Lollar looks out over her backyard on June 2, with a view of her neighbors in the distance. Lollar couldn’t see them before the 2013 Black Forest fire because of dense trees behind her orginal 1920s log cabin.

Beyond all the recent construction, the scars of the fire’s seemingly random rampage are still clear across the landscape here, and, for many, tell a story of regrets to come.

The charred forest along Wild Oak Drive in Black Forest is shown on July 9, 2013, almost a month after the Black Forest fire raged through the area.

Christian Murdock, The Gazette file

The charred forest along Wild Oak Drive in Black Forest is shown on July 9, 2013, almost a month after the Black Forest fire raged through the area.

Drive down any road in Black Forest and the invisible property lines are now apparent, where bunches of 10-foot saplings and low-hanging branches crowd beneath mature ponderosas, then almost immediately give way to a forest floor clear of undergrowth.

On a recent morning, one neighbor raked pine needles from her mostly treeless lawn under the shade of a tan sunhat, her home visible from the road.

Fifty yards down, the mouth of a neighboring driveway disappeared into the forest understory — a “bomb waiting to go off,” said David Poletti, a regional forester with the State Forest Service.

Poletti gestured to troops of saplings — called “doghair” for their short but thick clumping — creeping up to Vollmer Road.

“It’s a dire situation, to be pretty honest,” he added, noting that most properties that survived the fire look this way.

Mitigation laws don’t exist

Most, but not all.

As the Black Forest fire swept towards the upscale Cathedral Pines subdivision, the fire dropped down from the treetops to the ground, where it stayed, allowing firefighters to safely defend the community of luxury homes.

Standing on the edge of Cathedral Pines last week, Keith Worley, a forester with 30-years of experience in Black Forest, described how the fire stayed low as it moved through the subdivision, then, once it reached unmitigated land at the far side, swept back up into treetops via “ladder fuels.”

From that point, the fire raced another 7 miles east.

“Where we are standing today is one of the spectacular kinds of spots where we can say forestry and thinning and wildfire mitigation really paid off,” he said.

The mitigation in Cathedral Pines was successful at keeping the flames on the ground, despite high winds and through thickets of trees foresters would normally consider too dense to survive, Worley said.

He credits the subdivision’s developer, who cleared the land of many trees to create lots with a “Pikes Peak view,” before fire could.

In other areas of Black Forest, even now, residents cannot be persuaded to do the same kind of mitigation that spared Cathedral Pines.

No laws exist forcing residents to mitigate, even in an area and at a time when wildfires rage uncontrolled and exact greater and greater human and physical costs. El Paso County even voted to weaken some fire codes that had been in place at the time of the Black Forest fire.

Time doesn’t always bring wisdom, pointed out Black Forest resident Carolyn Brown, who chose to rebuild after her home burned in the fire, clearing her lot of almost 300 ruined trees to do so.

Brown is a volunteer at the nearby slash-mulch site, a nonprofit “Wildfire Mitigation and Recycling Program” that, for decades, has collected residents’ mitigated tree and brush debris and processed it into mulch.

“We were so busy and it was daunting how much people brought in,” said Brown, recalling long lines of cars and trucks backed up down Shoup Road, waiting to drop off cleared debris.

That continued for maybe two, three summers, after the fire.

“Some people, it takes a scare to motivate them,” she said. “And then, I guess, they forget.”

‘Bring in the masticators’

Some got lazy. Others, sentimental.

Worley calls it “tree hoarding,” when residents decide they can’t part with any trees.

In a report about the fire to then Gov. John Hickenlooper that Worley helped write for the Pikes Peak Wildfire Prevention Partners, the authors decided “willful ignorance” was the best term to describe those who could not be persuaded to thin trees. All residents of Black Forest shared in the consequences of such negligence, the report found.

“The lack of mitigation measures by many property owners allowed the Black Forest fire to quickly grow large and exhibit extreme fire behavior that devastated major portions of the entire community — not just those unmitigated parcels,” the report stated.

In some areas, the wind blew embers from the fire racing through the treetops and ignited homes away from the fire’s main front.

Frances Burke, who built her first house in Black Forest 55 years ago, takes her dog, Bella, for a morning walk through the treeless neighborhood along Wild Oak Drive. Burke gathered her two dogs, three cats and artwork when she evacuated June 11, 2013, in the early hours of the Black Forest fire. She lost everything she left behind, but rebuilt and moved into her new home within a year of the fire that destroyed more than 500 buildings.

Christian Murdock, The Gazette

Frances Burke, who built her first house in Black Forest 55 years ago, takes her dog, Bella, for a morning walk through the treeless neighborhood along Wild Oak Drive. Burke gathered her two dogs, three cats and artwork when she evacuated June 11, 2013, in the early hours of the Black Forest fire. She lost everything she left behind, but rebuilt and moved into her new home within a year of the fire that destroyed more than 500 buildings.

The excuses for not mitigating, also detailed in the report, included high cost, the time and physical exertion such efforts require, and a hesitation to hurt the natural appearance of the landscape or lose privacy screening.

Educating people to embrace a sunnier, more open forest with large ponderosas is a big part of Worley’s job.

In one case, he said, a woman claimed she could hear the trees he was thinning out mechanically on a property next to her land screaming as they died. He explained that all those trees could be lost to a catastrophic wildfire — a tragic end that could take her and her neighbors’ property with it, if nothing was done.

“She went from not wanting to cut any trees whatsoever to ‘bring in the masticators,’” he recalled, referring to a process in which heavy machinery is used to remove many trees at once on large swaths of land.

Healthy peer pressure

Modern wildfires are burning with more intensity, size and destructiveness than ever before, exacerbated by the effects of climate change throughout the American West and an ever-increasing number of people — 46 million — residing in Wildland Urban Interface areas nationwide, a zone that grows by some 2 million acres per year, according to the UL Fire Safety Institute.

Colorado Springs Forest Service Section 16 in Black Forest serves as a banner example, and map, of how proper mitigation can save nature, and people.

The 90-acre-square lot, near Vollmer and Burgess roads and leased from the State Land Board, features a public trail and was largely burned during the fire.

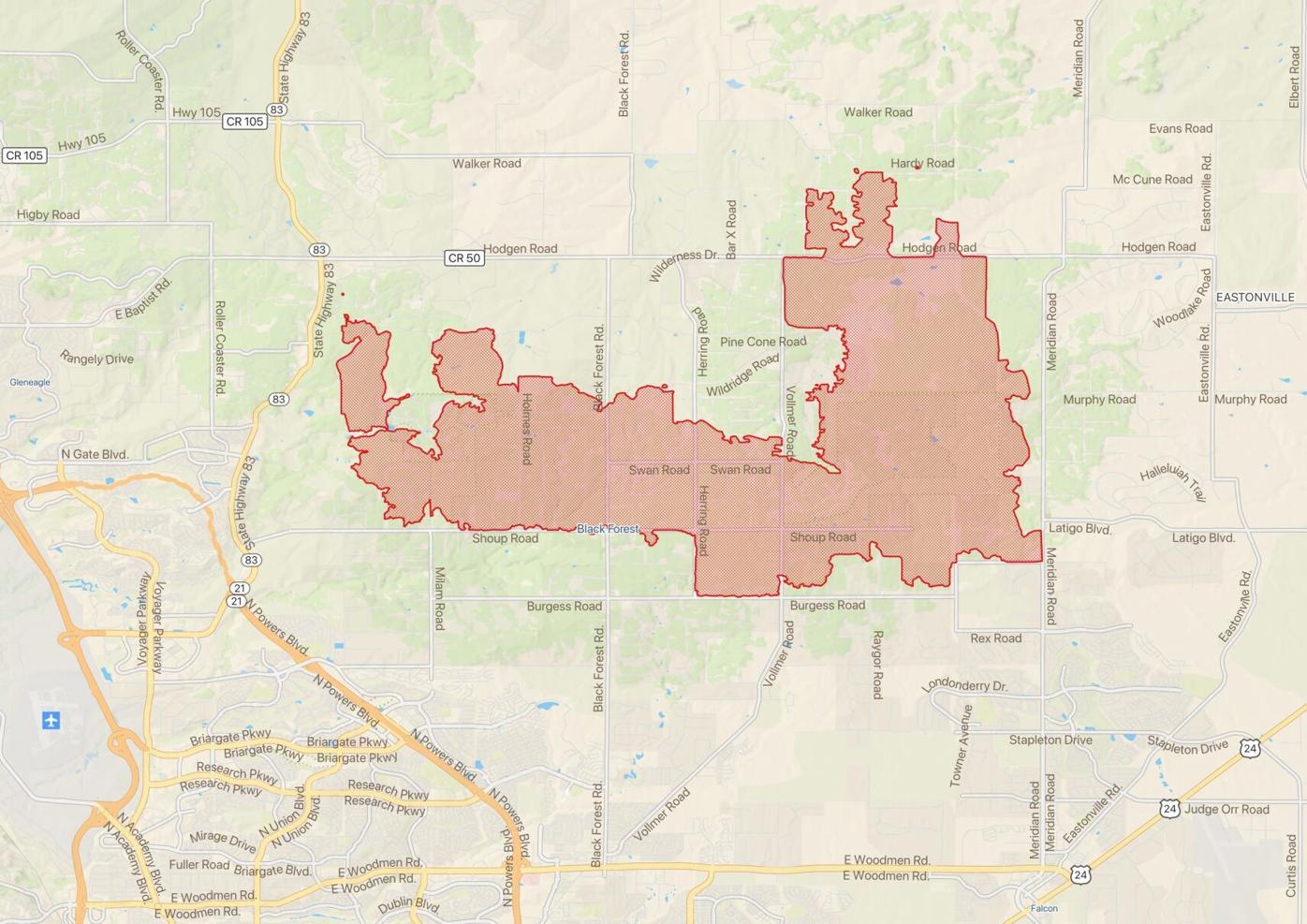

A map shows the final perimeter of the Black Forest fire, which burned over 14,000 acres and 500 structures during its nine-day rampage. The fire is believed to have started east of Colorado 83 and Shoup Road.

EVAN WYLOGE, Special to The Gazette

A map shows the final perimeter of the Black Forest fire, which burned over 14,000 acres and 500 structures during its nine-day rampage. The fire is believed to have started east of Colorado 83 and Shoup Road.

In the section’s burn scar, delineation between forest that was thinned and areas left dense before the fire is clear, with healthy mature trees, remnants of black char still coating the base of their trunks, facing a new meadow full of dead trees, called snags, and a tangle of burned sticks and piles of dead wood on ground.

On Thursday, June 8, 2023, deer walk through an open meadow created after the 2013 Black Forest fire.

Christian Murdock, The Gazette

On Thursday, June 8, 2023, deer walk through an open meadow created after the 2013 Black Forest fire.

That low-density, open-canopied “parked-out” look, as Poletti calls it, is the way nature intended a ponderosa forest to look.

Mastication and logging, however, have often drawn the ire of some ecologists who argue that the methodic spacing — also jokingly called “jail bar” mitigation — actually harms natural forest succession processes, eliminating young trees altogether, as well as Abert’s squirrel and goshawk habitats.

Still, if people insist on living in these fire-prone areas, Poletti said, they must be willing to do with chainsaws and masticators what fire did in the past to “get ahead” of catastrophic blazes.

“If you own any type of property with trees on it in Colorado, it’s your obligation to be a steward of the land,” Poletti said. “Because, if you’re not going to manage your forests, nature’s gonna do it for you, and you’re not gonna like the way nature does it.”

According to Lt. Erik Beckstrom with Black Forest Fire Protection District, the department works with state foresters, like Poletti, to provide risk assessments, complete with scorecards, for residents to highlight places, like an unscreened soffit vent or pine needles on the patio furniture, that need improvement.

Young pine trees grow under the older trees along Black Forest Road south of Shoup Road Thursday June 8, 2023.

Christian Murdock,The Gazette

Young pine trees grow under the older trees along Black Forest Road south of Shoup Road Thursday June 8, 2023.

“(Residents are) lowering the likelihood of us being able to save certain aspects of their property if they’re unwilling to mitigate and it also puts their neighbors at risk, plain and simple,” Beckstrom said, recommending a 30-foot “defensible space” around a property, mostly clear of trees, that can accommodate engines or other emergency vehicles.

Developers can offer a kind of built-in mitigation plan while constructing neighborhoods, and other private groups have proven particularly effective in managing individual thinning efforts.

Federal and state grants can help.

Homeowners associations, Poletti said, can apply for and distribute funding to individual homeowners. The state forest service’s Forest Restoration and Wildlife Risk Mitigation program, for example, had a $15 million pool available to local governments, forestry nonprofits, utilities and community groups for its 2022-2023 round.

One beneficiary of this grant is the Forest Gate neighborhood, which sits catty-corner to Section 16 and narrowly escaped the flames a decade ago.

Forest Gate HOA president Malcom Johnson, a Black Forest resident of 15 years, said the community received a total of $48,000 and has distributed $18,000 across eight major projects aimed at lessening the risk of wildfire.

Three more projects are “in the pipeline,” he said. Under the program, the state may reimburse homeowners up to 50% of mitigation costs.

The Black Forest fire was a “wake-up call” for his neighbors, Johnson said, spurring them to become a certified Firewise Community — a national program where residents, firefighters and government officials promised to demonstrate actionable plans to minimize fire risk — by 2014.

There are eight Firewise Communities, including Forest Gate, in or directly near Black Forest, according to the National Fire Protection Association, and nearly 1,000 certified communities across 40 states.

Though the HOA cannot enforce mitigation, its education efforts and residents’ strong awareness of neighborly responsibility, and perhaps a healthy brand of peer pressure, has led most of Forest Gate’s 50 2.5-acre or 5-acre lots to feature some degree of mitigation, he said.

“That low-key, friendly neighbor approach has worked tremendously well,” Johnson said.

Forest Gate is even looking to spread some grant funds to neighboring communities, bolstering forest thinning beyond manmade picket fence lines.

“Fire recognizes no boundaries,” Johnson said.

What about evacuations?

Moving back to a community ravaged by fire was never a question for Laura Lollar.

“I love the community. I lived downtown for 12 years and I wanted the peace and quiet that came with living out here in the forest,” she said. “It’s kind of a joke now at this point, ‘cause it’s not peaceful and quiet anymore, but it really was not an option for me not to build.”

The only option was what kind of a house.

She opted for a split-level stucco.

How she thinks about life in a fundamentally changed community that could burn again, has evolved as well. She mitigates the property, and she has a plan in place should that not prove enough.

Next time she will know exactly which keepsakes and essentials to grab before she packs up the car and makes her escape.

“There are more people living in Black Forest now than there were 10 years ago, but thankfully we’ve got enough roads leading in and out of here,” Lollar said. “It’s not like the Mountain Shadows area (during the Waldo Canyon fire), where they only had a couple outlets. We’ve got plenty of escape routes.”

An evacuation simulation run by The Gazette, using the 2010 Census figure of 13,116 and the 2020 Census figure of 15,097 (a change of 15.1%), found encouraging results: a roughly 1-hour, 20-minute evacuation time, based on moderate simulated traffic and moderate simulated traffic “events,” such as minor car accidents.

Such simulations, however, didn’t factor in situations evacuees potentially could be facing as they flee for their lives from a burn zone whose only exits are lined with unmitigated fuel, Poletti pointed out.

Even without roadblocks, such as fallen trees, roads can get “pinched off” when drivers are unwilling to drive through smoke or flames. When doghair is growing right up to the road, and it’s burning black, evacuation plans might not happen as envisioned.

“When the big fire comes, all this fuel is going to burn super-hot and put off a lot of black smoke and embers … and people won’t be able to evacuate,” he said. “All it takes is one car to get spooked and stop, and then you have a traffic jam.”

The Gazette’s Mary Shinn contributed to this report.