Denver Public Schools safety plan includes mental health emphasis, training

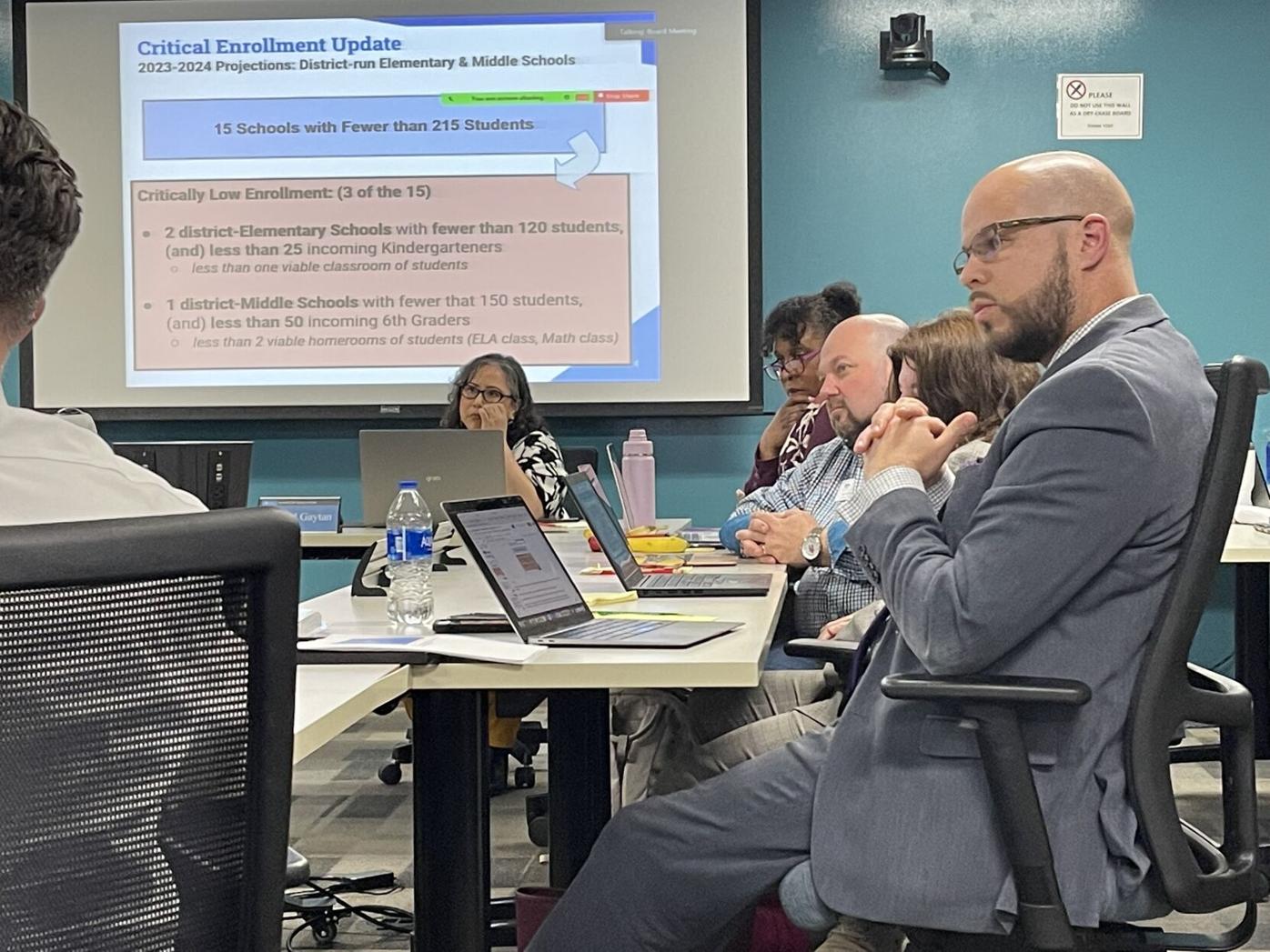

FILE PHOTO: DPS Superintendent Alex Marrero listens to a staff presentation on enrollment projections during a board meeting discussion about possible school closures on Thursday Feb. 23, 2023. Friday, Marrero release the final draft of the district's school safety plan.

Nicole C. Brambila/Denver Gazette

Denver Public Schools Superintendent Alex Marrero released the final draft of the district’s comprehensive safety plan Friday.

The plan is chock-full of acronyms and education buzz words, but short on goal-oriented details.

“This was never going to be addressed on the granule level,” Marrero told The Denver Gazette Friday.

In the aftermath of a shooting that wounded two administrators at East High School — the district’s flagship campus — the Board of Education directed Marrero to create a comprehensive safety plan.

Marrero released two previous draft versions.

In those drafts, as in this one, the plan discusses the use of armed police on campus, called school resource officers (SRO), and weapon detection systems — which are currently used only for athletic and other events at the request of administrators.

In the wake of the East High shooting, the board temporarily reintroduced police, who were removed after the district cut ties with the Denver Police Department in 2020.

The 57-page plan lacked specificity.

For example, the report noted that the district’s Department of Social Work and Psychological Services “has over 400 providers” that serve nearly 90,000 students. Given the mental health crisis unfolding in the United States, the plan acknowledges the need for additional mental health providers.

‘It won’t work’

The mental health crisis isn’t happening in some far-off place.

Two years ago, the Children’s Hospital Colorado declared a “state of emergency” — a first in the health system’s history — after seeing a 57% increase over two years in pediatric patients coming to the emergency department with mental health concerns.

Suicide, according to the state health department, is now the leading cause of death for Colorado’s youth and young adults. And it’s the second-leading cause of death in the U.S among those age 10-to-14 and 25-to-34, federal data shows.

According to Marrero’s safety plan, a committee is developing a manual that outlines “workload considerations” for special education teachers and each specialized service provider discipline, as well as a process for accountability and workload audits for educators.

But there is no mention in the plan of what the workload currently is, what it should be, nor how many providers — and at what cost — could be required.

The National Association of School Psychologists recommends one psychologist for every 500 students. Last school year, Colorado had one school psychologist for every 942 students, according to the National Association of School Psychologists.

The American School Counselor Association recommends an even greater ratio: One school counselor for every 250 students.

The district is committed to providing at least one mental health profession for each of the district’s roughly 200 schools, Marrero said.

But he stopped short of committing to national recommendations.

“To simply place a ratio, it won’t work and it won’t be well received by the community,” Marrero said.

‘Exciting parts’

Without more specificity, it is unclear what the district’s benchmark is.

Students with a disability, or perceived disability; those on support plans or experiencing mental health and behavioral concerns — which require enough staff to identify these students — “may require a tier two or tier three level of mental health supports,” according to the plan.

Students’ mental health cannot be under stated, which is likely why Marrero’s plan spends so much time discussing the district’s effort to address it.

Good mental health is critical to relationship building, decision making and success in school and life.

And yet, six in 10 youth nationally with major depression do not receive care, according to Mental Health America. Without intervention and support, the more severe consequences become.

The student accused of shooting Jerald Mason and Eric Sinclair on March 22 later committed suicide, leading to a robust public discussion about students’ mental health.

Marrero’s safety plan also touches on the need to ensure the district’s universal screening and social emotional learning supports are effective with the goal of matching students with the appropriate level and type of mental health intervention.

As in previous versions of his safety plan, Marrero included recommendations to revise the discipline matrix used to address problematic student behavior, which has been criticized as too lax. Other recommendations included annual training, safety audits and screening, all things Marrero said were “exciting parts” of the plan.

‘Tradeoffs’

Theresa Peña said Marrero’s safety plan hit a lot of the right notes.

Perhaps too many notes.

“They have a huge laundry list of things to do, so, they need to prioritize,” said Peña, a member of the Parents-Safety Advocacy Group (P-SAG) and a former school board member. “There will be tradeoffs.”

Formed after the East High shooting, P-SAG is a grassroot organization concerned about student safety. The group has also advocated for greater transparency.

But what concerns Peña is what she described as an inherent flaw in the plan: It lacks specificity, goals and timelines.

DPS, Peña said, has a history replete with “really great ideas,” but terrible outcomes.

Equally as troubling to Peña is the insistence on administrators conducting student searches rather than law enforcement. Marrero’s plan calls for DPS’ Department of Climate and Safety providing “additional support in conducting searches, especially where weapons may be present.”

The two administrators shot in March were in the process of having a student search conducted.

“I guess we’re going to have to have a multi-million lawsuit to figure that out,” Peña said.

Tasked with creating a comprehensive safety plan within 14 weeks — swift for a public entity by any measure — Marrero pivoted with feedback he received on his earlier drafts.

For instance, Marrero’s first draft was widely criticized for punting on the return of school SROs by recommending school leaders make the decision about cops on campus. He also recommended individual schools decide whether to use weapons detection systems.

He made a reversal in his second draft, recommending the board of education weigh in on SROs, which they did in a split decision on June 15.

The vote ended months of speculation and reversed a 2020 decision under a previous board to remove cops from campuses over concerns about the school-to-prison pipeline — the disproportionate tendency of minors from disadvantaged backgrounds to become incarcerated because of harsh school policies.

Critics also blasted Marrero’s initial draft for its lack of clarity on which measures in the plan were new.

Marrero’s weapons detection recommendation, which also received mixed opinions, will remain a site-based decision for each campus, according to the final plan.

To read the full plan, visit https://superintendent.dpsk12.org/safetyplan/.