Colorado poised for cool, wet fall after summer return to drought conditions, climatologist projects

Q2Fyb2wgVGthY2ggd2Fsa3MgdGhyb3VnaCBmbG93ZXIgcGVkYWwgY292ZXJlZCBwdWRkbGVzIGFmdGVyIGV4aXRpbmcgaGVyIHRyYWluIG9uIGhlciBjb21tdXRlIGhvbWUgZHVyaW5nIGEgcmFpbnN0b3JtIG9uIFdlZG5lc2RheSwgTWF5IDEwLCAyMDIzLCBhdCB0aGUgUlREIGxpZ2h0IHJhaWwgTWluZXJhbCBTdGF0aW9uIGluIExpdHRsZXRvbiwgQ29sby4gKFRpbW90aHkgSHVyc3QvRGVudmVyIEdhemV0dGUp

VGltb3RoeSBIdXJzdC9EZW52ZXIgR2F6ZXR0ZQ==

It was nice while it lasted.

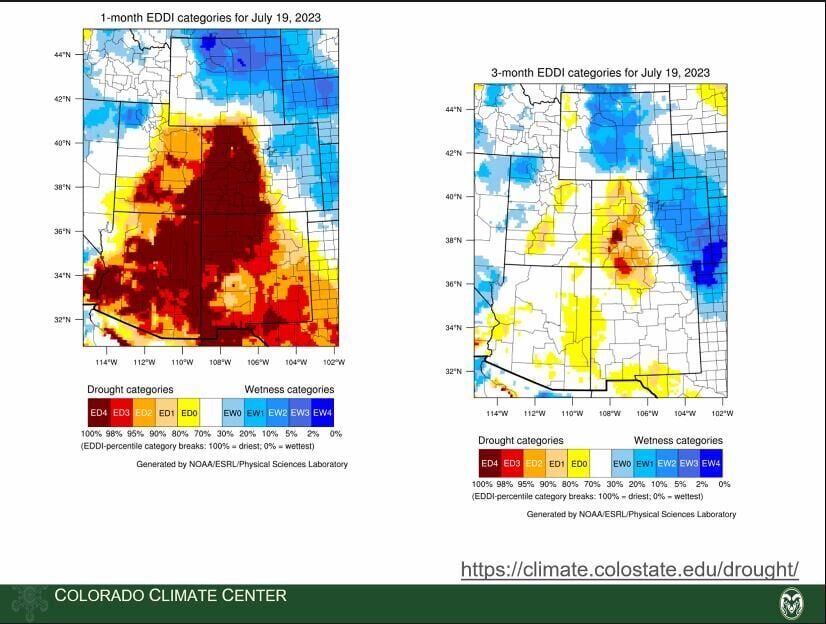

The brief respite from drought is over, with southwestern Colorado now seeing low levels of drought after “bone-dry” conditions for the past month.

Still, water watchers with the state’s Water Availability Task Force still had much to celebrate Tuesday. Almost every major reservoir in the state is full or nearly so, save for Navajo Reservoir in southwestern Colorado. An El Niño weather pattern this fall could mean cooler and wetter conditions, after three years of hot, dry weather from a La Niña pattern.

Peter Goble, a climatologist with Colorado State University’s climate center, said June was 1.2 degrees Fahrenheit below the 20th-century average. He reported the first nine months of the water year, which starts starts on Oct. 1, was the coolest since 1993.

That means less demand on reservoirs, above average soil moisture conditions and less evaporative demand. Overall, that’s led less demand for water from water providers.

Evaporative demand, Goble said, shows the “effective thirst of the atmosphere for water vapor, or how quickly water in soils, lakes, streams and reservoirs get pulled out for evaporation. It depends not just on temperature but on surface humidity, cloud cover and wind speeds.”

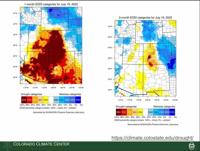

While evaporative demand was low between April and June, dry conditions in the last month show how quickly that can change. Evaporative demand has ramped up in southwestern Colorado and the Western Slope, both which are now seeing bone-dry conditions and low-level drought.

Evaporative demand between April and June, and in the last 30 days. Courtesy Colorado Climate Center.

Evaporative demand between April and June, and in the last 30 days. Courtesy Colorado Climate Center.

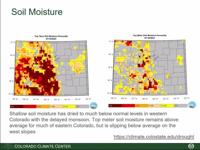

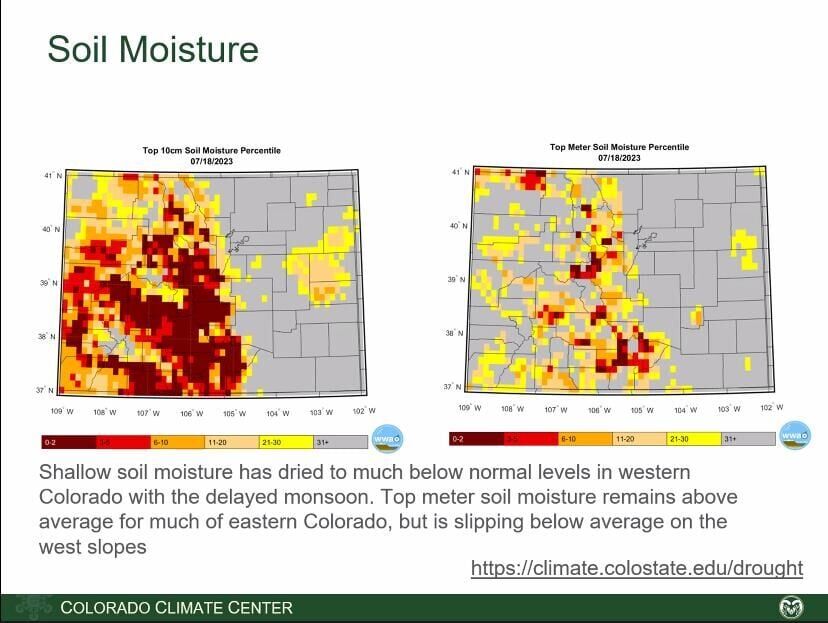

Soil moisture is another harbinger. When things go dry, it’s the first indicator, Goble said. Climatologists look at the first 10 centimeters of soil and the top meter as indicators. For the Western Slope, those soils are starting to show dry conditions.

Soil moisture, showing the Western Slope drying out. Courtesy Colorado Climate Center.

Soil moisture, showing the Western Slope drying out. Courtesy Colorado Climate Center.

Goble also looks at vegetation, and how well vegetation absorbs near-infrared radiation, a part of the photosynthesis process.

The Eastern Plains are more green than in a normal year, which is to be expected, he said. But in the middle of the state, including the San Luis Valley and into some of the high country, he said there are signs of pre-drought or moderate drought stress.

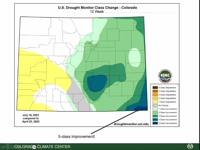

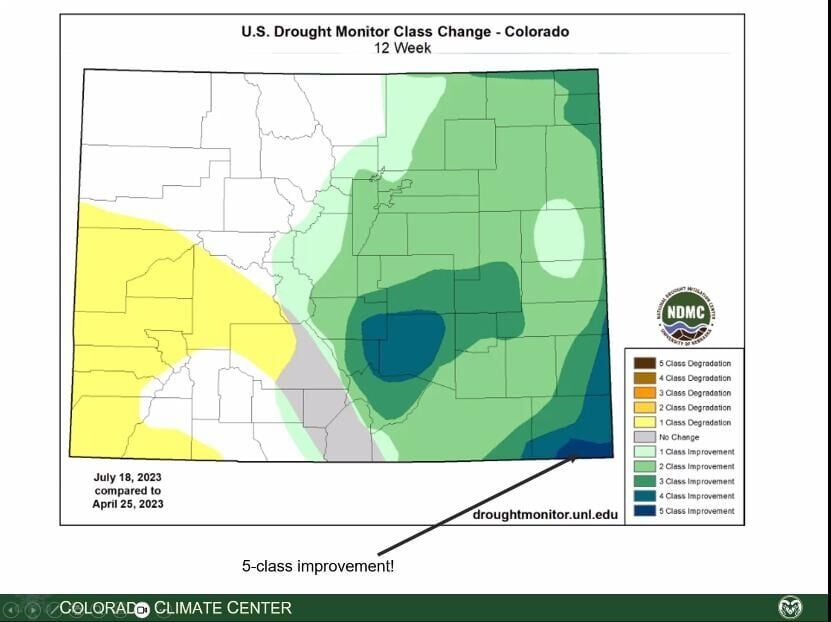

The U.S. Drought Monitor now shows low-level drought all over the Western Slope and most, but not all, of southwestern Colorado. What the drought has missed so far is the San Juan mountains, which had a good winter with its snowpack, and there is still quite a bit of snow at around 12,000 feet, Goble said.

Southeastern Colorado, which had the worst drought conditions in the state just a few months ago, has made a remarkable recovery, Goble said. Some parts of the Eastern Plains had their all-time wettest month, he added.

The U.S. Drought Monitor shows a dramatic improvement in drought conditions in southeastern Colorado. Courtesy Colorado Climate Center.

The U.S. Drought Monitor shows a dramatic improvement in drought conditions in southeastern Colorado. Courtesy Colorado Climate Center.

For the fall, Goble says there’s a good probability for El Niño conditions, which means cool and wet extremes, except for the San Luis Valley.

“It’s like playing a hand of poker with a couple of extra aces in the deck,” he quipped.

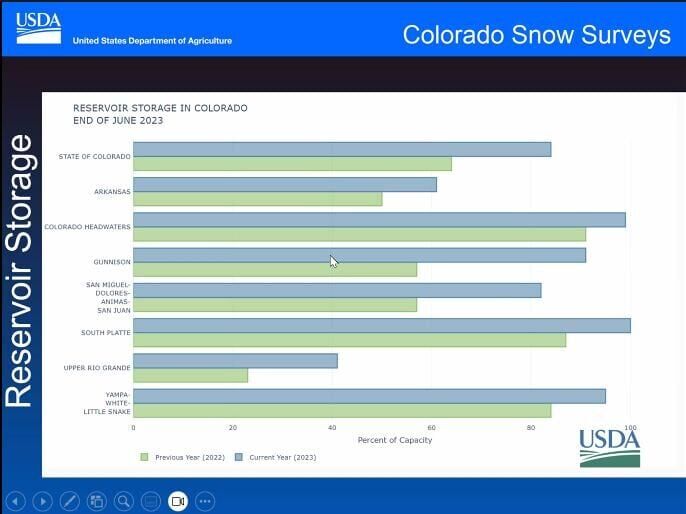

More good news is just how much water is in the state reservoirs, according to Karl Wetlaufer with the Natural Resources Conservation Services, part of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Overall, the state’s precipitation for this water year is at 108% of median, Wetlaufer reported.

At the Yampa/White/Little Snake basin, precipitation has been at 115% of median, which has resulted in dramatic increases in water levels in the region’s reservoirs.

It’s much the same for the Colorado River Basin, with the majority of reservoirs showing impressive improvements. “It’s a good situation in Colorado storage as we exit the runoff season,” Wetlaufer said.

In the Gunnison basin, home to Blue Mesa, the state’s largest reservoir, Wetlaufer said there’s considerable improvement between where the reservoir was a year ago and now.

The news isn’t quite as good in the southwestern Colorado basin that includes the San Miguel, Dolores, Animas and San Juan rivers; while the reservoirs are at or above normal levels, the region’s largest — Navajo — is below normal, and three months of dry and hot conditions haven’t helped.

The San Luis Valley, home to the Rio Grande River, has been bone-dry for the last month and meager snowpack didn’t help.

A year ago, Wetlaufer said, reservoirs around the state averaged about 70% of capacity. Now, it’s closer to 85% to 90%, he said.

Reservoir storage levels, 2022 to 2023. Courtesy Natural Resources Conservation Service.

Reservoir storage levels, 2022 to 2023. Courtesy Natural Resources Conservation Service.

What all this means for water providers: less water use this summer. Denver Water’s Jordan Soldano said the reservoirs they rely on are 97% full and summer demand is lower than normal. Colorado Springs Utilities’ Ithan Bravo said their reservoirs are 92% full and they’re seeing the same reduction in demand.