A Colorado veteran needed help. He ended up dead after the VA referred him to a nursing home

The terrible chain of events began three years ago in Grand Junction when the Veterans Health Administration made a questionable referral for an elderly veteran named Ernest Griffiths Jr. to enter a private-sector nursing home for his dementia care.

It ended Feb. 25 with suspected felony neglect after a foot wound went untreated and sepsis swept through his 83-year-old body, killing him.

To this day, no one has been held accountable.

His death offers a disturbing look at the lack of consequences for nursing homes after deaths due to alleged negligence or substandard care. It also raises questions about how the Department of Veterans Affairs awards contracts to nursing homes in order to meet the rising need of aging veterans.

A Gazette investigation found that 13 of the 28 privately owned or community-based nursing homes in Colorado with VA contracts are rated substandard by another branch of the federal government. One in four have the lowest possible low rating.

Ona Griffiths knew none of that back in fall 2020. She only knew she needed help. The once jovial character she had married 47 years before, a man with a quick smile and corny joke at the ready, was slipping away from her, his once sharp mind increasingly clouded.

Her husband, known simply as Griff, no longer remembered familiar faces and often didn’t know where he was. He would become agitated by his confusion, sometimes not sleeping for 36 hours straight.

That meant she didn’t sleep, either, fearing what would happen if she didn’t keep watch. The anxiety and a crush of helplessness were starting to take a toll on her health, as well. A family doctor and a social worker both gently suggested she find a long-term residential nursing home for her husband to keep him safe.

“It’s time,” she was told.

Because her husband was a disabled veteran, his care could be paid for by the VA. He served as a stateside mechanic in the U.S. Air Force for nine years, enlisting in August 1957 and leaving in July 1966 as a staff sergeant, making him part of the Vietnam War era. He was eligible for full health care benefits because of a significant hearing loss thought to be tied to his work on aircraft engines.

So, Ona Griffiths turned to the VA’s Western Colorado Health Care System. The VA, in turn, recommended three options, but only one had space and the ability to care for him, she said. On Oct. 19, 2020, her husband moved into Mantey Heights Rehabilitation and Care Center, an 88-bed, for-profit nursing home about 15 miles from their home in Fruita.

Mantey Heights is owned by Diversified Healthcare Trust, a publicly traded real-estate investment trust with headquarters in Massachusetts. It is managed by Utah-based Stellar Senior Living, which owns or operates 34 long-term residential and senior-living facilities across nine Western states. There are 12 in Colorado.

The bill for Ernest Griffiths’ care topped $9,000 a month, paid for by the VA, his wife said.

At first glance, Mantey Heights looked pleasant enough, she thought. She was unable to tour it because of pandemic restrictions. Still, she signed the admission papers with the promise that her husband would be looked after.

She had no reason to question the VA’s recommendation. And, in truth, she felt she had no choice.

“I figured they knew what they were doing,” she said of VA, “I trusted them.”

Aging veterans

Nearly half, 48%, of veterans enrolled in VA benefits were 65 or older as of last year, according to the national VA office.

In the next 13 years, the number of VA enrollees 85 or older is expected to increase by 73%, rising from 544,000 to just more than 942,000, the VA said.

While the VA has its own nursing homes, known as community living centers, there are not enough beds to fill the need. Nationally, there are 134 VA-run nursing homes with a total of 16,664 beds. In Colorado, there are only two, in Grand Junction and Pueblo, with a total of 65 beds.

Another option is state-run nursing homes that have a contract with the VA but they, too, are limited in the number of beds. Nationally, there are 165 such facilities. In Colorado, there are five.

So, the VA looks to the private sector to help bridge the gap.

As of last year, it contracted with about 8,000 private or community-owned nursing homes nationwide to care for about 36,000 veterans.

Currently in Colorado, there are 28 such nursing homes with VA contracts, serving roughly 900 veterans. Most are for-profit with a small number of nonprofit or community-run.

A 2020 U.S. Government Accountability Office report found that private-sector and community-owned nursing homes were the fastest-growing segment among the three types of residential care for veterans between 2014 and 2018, rising 26%. That compares to 1% growth among state-owned facilities and a drop in use among VA-owned nursing homes during those years, the report said.

It is a trend expected to continue in coming years, with a projected 80% rise in contracts to private-sector and community-owned nursing homes and a 149% growth in cost between 2017 and 2037, according to the GAO report.

To win a VA contract, nursing homes must first apply and are then scrutinized based on a rating system developed by the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, the VA said in an email to The Gazette. CMS is the federal agency within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services that oversees federally funded nursing homes.

The CMS tool rates facilities on a star system from one to five, with five stars being the highest. Three categories are combined to reach an overall rating: health inspections, staffing and quality measures. The latter looks at a combination of factors such as overall care, if a resident received a flu shot, if they are in pain, or if they are losing weight.

Violations and penalties against facilities are also included on the CMS website.

The VA said it uses the CMS tool to “identify high-quality facilities,” and that “an emphasis is placed on contracting with and utilizing nursing homes with higher ratings.” Ongoing performance is measured through the rating system as well as on-site interviews with veterans, a review of medical records and meetings with facility administrators, the VA said.

But The Gazette, using the same star-rating system, found that 13 of the 28 — nearly half — of the Colorado nursing homes holding VA contracts are currently considered below average with ratings of one or two stars.

In fact, the most common rating within the 28 was the lowest possible, The Gazette found.

Seven were ranked a “one,” six were ranked “two,” four were ranked “three,” five were ranked “four,” and six were ranked “five.”

VA contracted nursing homes in Colorado:

- La Villa Grande Care Center, Grand Junction, for profit, 96 beds, $29,358 in federal fines in past three years. Flagged for potential abuse. THREE STARS

- Mantey Heights Rehabilitation and Care Center, Grand Junction, for profit, 88 beds, $132,772 in federal fines in past three years. TWO STARS

- Mesa Manor Center, Grand Junction, for profit, 89 beds, $188,278 in federal fines in past three years. Flagged for potential resident abuse. ONE STAR (no veterans being referred at this time because of rating)

- Valley Manor Care Center, Montrose, non-profit, 101 beds, $26,325 in federal fines in past three years. Flagged for potential resident abuse. TWO STARS

- Adara Living, Broomfield, for-profit, 210 beds, $75,972 in federal fines in past three years. THREE STARS

- Holly Heights Nursing Center, Denver, for profit, 133 beds, $9,506 in federal fines in past three years. FOUR STARS

- Aviva at Fitzsimmons, Aurora, for-profit, 92 beds, $1,521 in federal fines in past three years. Delayed inspections. FIVE STARS

- Clear Creek Care Center, Westminster, for-profit, 80 beds, $19,045 in federal fines in past three years. THREE STARS

- Juniper Village- the Spearly Center, Denver, for profit, 135 beds, $48,157 in federal fines in past three years. Flagged for potential resident abuse. ONE STAR

- Neurorestorative Colorado, Littleton, for profit, 36 beds, $17,869 in federal fines in past three years. Delayed inspections. FIVE STARS

- Health Center at Franklin Park, Denver, non-profit, 86 beds, $154,992 in federal fines in past three years. ONE STAR

- Prestige Care Center of Morrison, Morrison, for profit, 180 beds, $198,929 in federal fines in past three years. Inspections delayed. ONE STAR

- St. Paul Health Center, Denver, for profit, 150 beds, $55,926 in federal fines in past three years. ONE STAR

- Riverdale Post Acute, Brighton, for profit, 105 beds, $1,840 in federal fines in past three years. FOUR STARS

- Summit Rehabilitation and Care, Aurora, for profit, 110 beds, $0 in federal fines in past three years. FIVE STARS

- Rowan Community Inc, Denver, for profit, 65 beds, $0 in federal fines in past three years. FOUR STARS

- Westlake Care Community, Lakewood, for profit, 67 beds, $3,250 in federal fines in past three years. FIVE STARS

- Sierra Post Acute, Lakewood, for profit, 101 beds, $43,022 in federal fines in past three years. Flagged for potential resident abuse. TWO STARS

- Silver Heights Skilled Nursing and Rehabilitation, Castle Rock, for profit, 91 beds, $109,220 in federal fines in past three years. ONE STAR

- Belmont Lodge Healthcare Center, Pueblo, for profit, 120 beds, $68,124 in federal fines in past three years. TWO STARS

- Bent County Healthcare Center, Las Animas, government, 56 beds, $7,345 in federal fines in past three years. FOUR STARS

- Forest Ridge Senior Living, Woodland Park, for profit, 80 beds, $0 in federal fines in past three years. Inspections delayed. FIVE STARS

- Fowler Health Care Center, Fowler, for profit, 45 beds, $30,082 in federal fines in past three years. Inspections delayed. FIVE STARS

- Hildebrand Care Center, Canon City, for profit, 80 beds, $21,658 in federal fines in past three years. ONE STAR

- Holly Nursing Care Center, Holly, for profit, 45 beds, $60,777 in federal fines in past three years. TWO STARS

- Pioneer Health Care Center, Rocky Ford, for profit, 101 beds, $89,023 in federal fines in past three years. TWO STARS

- Rock Canyon Respiratory and Rehabilitation Center, Pueblo, for profit, 141 beds, $148,891 in federal fines in past three years. Flagged for potential resident abuse. THREE STARS

- Walbridge Memorial Convalescent Wing, Meeker, hospital district, 30 beds, $51,509 in federal fines in past three years. FOUR STARS.

Source: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services as of Oct. 4

In addition, six Colorado facilities with VA contracts were separately flagged by CMS for “potential issues related to abuse.”

“If the VA is sending vets to substandard care, that in itself is a scandal,” said Robert Blancato, the national coordinator of the Washington-based Elder Justice Coalition.

21 calls to Adult Protective Services

“The VA would love to see more private nursing homes rate higher to give our aging veteran population the care they deserve and need,” the agency said in its emailed statement.

It added that it meets with contracted facilities regularly and will do so more frequently if problems arise. “Facilities that fail to meet VA quality standards, including a review of veteran satisfaction and any relevant events, may be terminated from their partnership with the VA,” the agency statement said.

Veterans would then be relocated to other VA-contracted nursing homes, “where their quality of care and safety can be ensured,” the email said.

Mantey Heights, which cares for about a dozen veterans, had an overall CMS rating of two stars as of Oct. 4: one star for “health inspections,” two stars for “staffing” and five stars for “quality measures.”

It is unclear how the quality measurement was determined, especially considering citations from May 2022 that included failure to bathe residents and failure to address wounds, according to CMS records and the ProPublica website Nursing Home Inspect.

Mantey Heights was issued nearly $133,000 in total federal fines between 2021 and 2022, according to CMS.

In addition, the nursing home paid a $540,000 civil fine in January 2023 for the unauthorized filing of claims, which it self-disclosed, according to the federal Office of Inspector General. No other details of that case were available.

And following Ernest Griffiths’ death, a police report, obtained by The Gazette, said that the state’s Adult Protective Services was called to Mantey Heights 21 times in the previous year. The nature or resolution of those calls was not disclosed, and the state agency declined to comment.

Evrett Benton, CEO of Stellar Senior Living, said in an interview that his company took over management of Mantey Heights in September 2021, describing it as “one of the most difficult properties” it had. He added that many of the problems cited predated his company taking over.

Still, he said his company has worked to improve, replacing staff, pumping money into capital improvements, and working with authorities to correct violations.

“Every day, we are getting better,” he said.

Weight loss, unkempt appearance

On the evening of Feb. 14, Ona Griffiths got a call from Mantey Heights, saying that her husband had a sore on his foot and the staff wondered if it would be OK if a doctor checked it.

“Of course,” she replied, puzzled by the question. She had planned to visit for Valentine’s Day but wasn’t feeling well and decided to skip it. She said there was nothing in the tone of the call to trigger alarm.

Griffiths had, however, become increasingly concerned at the level of basic care her husband was receiving. When she first signed the contract in 2020, she specifically asked about bathing him, because that was something she was unable to do at home.

She said she was assured the staff would do it.

After he was admitted, Griffiths could not visit him for months because of COVID. When she finally saw him, in spring 2021, she was horrified at his appearance. His hair and beard were long and straggly, his clothes filthy and he clearly was not bathed. When she confronted the staff, she said she was told there was nothing it could do if he didn’t want to bathe.

“I thought, ‘isn’t that’s why he was in here? To take care of him?’” Griffiths recalled.

She also worried that he was losing weight, maybe as much as 40 pounds in the two years he was there.

In January 2023, she met her husband at a local oral surgeon’s office to have some of his teeth pulled and was repulsed to see dried food caked into his hair and staining his clothes. “Couldn’t you have cleaned him up before you brought him?” she asked the driver.

“I didn’t notice,” she said the driver replied.

At one point, she said she complained to the VA about the conditions and was told she needed to take up any issues with the facility. “I felt like they had washed their hands of him,” she said.

Both the VA and leadership of the company that runs Mantey Heights told The Gazette they could not comment on a specific veteran’s care because of patient privacy laws.

The morning of Feb. 15, the next day, Griffiths got another call from Mantey Heights, this one more urgent. Her husband was being taken to Community Hospital in Grand Junction, because his foot had not improved. Confused, she asked what the doctor had found the night before. She said she was told the doctor never came, because she was out of town.

When Griffiths and her daughter arrived at the hospital’s emergency room, her husband was curled in a fetal position, unresponsive. “I thought he was dead,” she said.

There was a large, oozing wound on his left ankle surrounded by scabs and sores from previous wounds. “Your husband is very, very ill,” the doctor warned her, adding that it was impossible that it happened overnight.

The last time Griffiths had visited her husband at Mantey Heights, he had been asleep with a blanket over his feet, so she does not know when the wound first appeared.

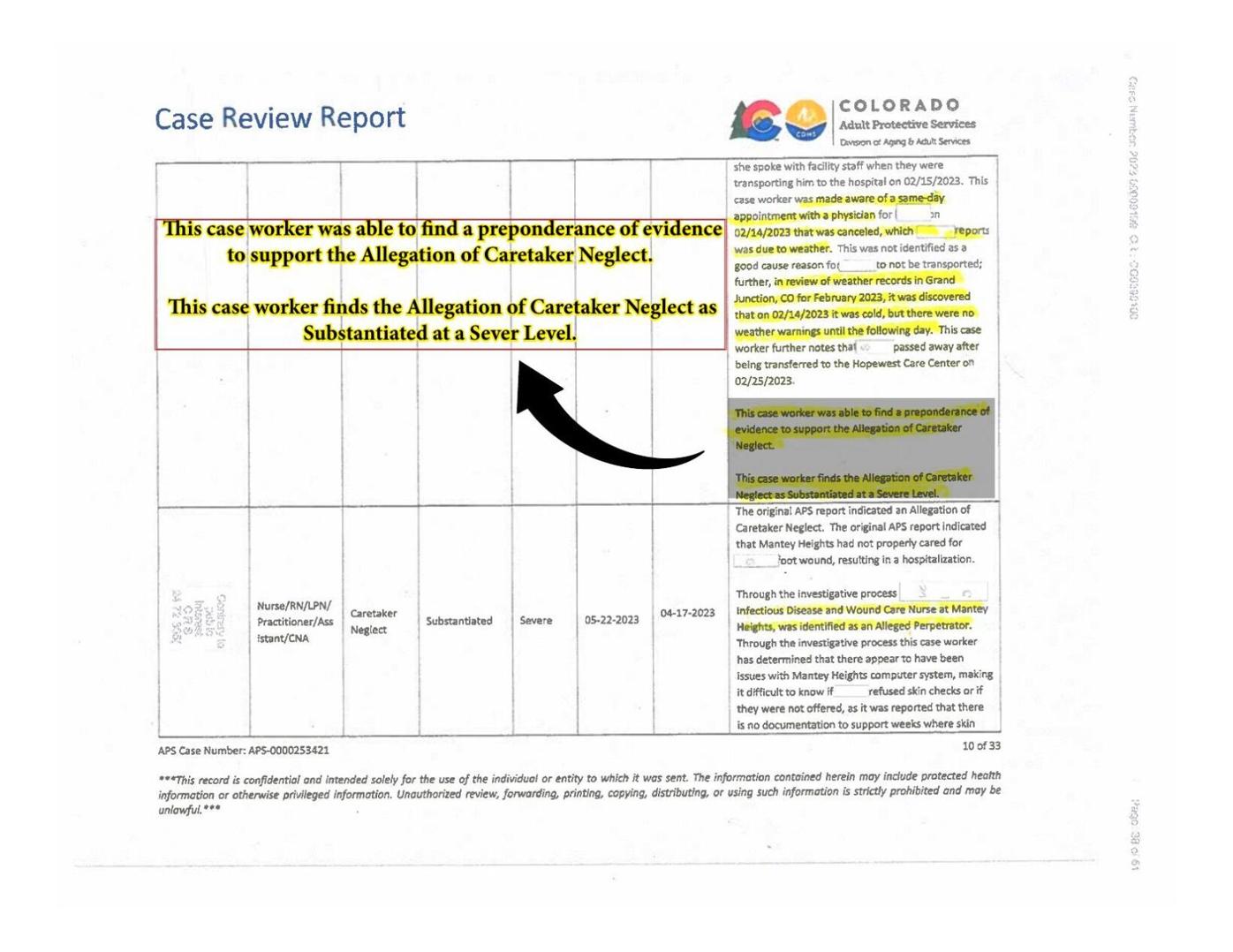

When Griffiths arrived at the hospital, a nurse called state Adult Protective Services to report suspected neglect. The caseworker called the Grand Junction Police Department. In the weeks that followed, both investigated. The state’s Department of Regulatory Agencies also reviewed the case.

Grand Junction police detective Zachary McCullough launched an investigation into suspected crimes against at-risk people and negligence resulting in death, both felonies.

He and an Adult Protective Services caseworker said in their internal reports that despite a standing order for weekly skin checks, it was unclear how often Griffiths received them.

A Mantey Heights worker told the Adult Protective Services caseworker that care at Mantey Heights had “decreased in recent months.”

The caseworker report said the story about why Griffiths was not seen by a doctor on Feb. 14 did not match what Ona Griffiths said she was told. An employee at Mantey Heights said it was probably because the weather was bad, not that the doctor was out of town. The caseworker wrote in her report that she checked with the Grand Junction National Weather Service office and on Feb. 14 it was cold but not storming.

The nursing home also allegedly dismissed the ER doctor’s assessment that Ernest Griffiths’ wound could not have become so serious overnight. The caseworker said in her report that she was told by Mantey Heights staff that ER doctors often became concerned over “common geriatric things.”

In her conclusion, the caseworker wrote she “was able to find a preponderance of evidence to support the allegation of caretaker neglect.” She further determined “the allegation of caretaker neglect as substantiated at a severe level. “

In addition, she identified two employees as potentially culpable.

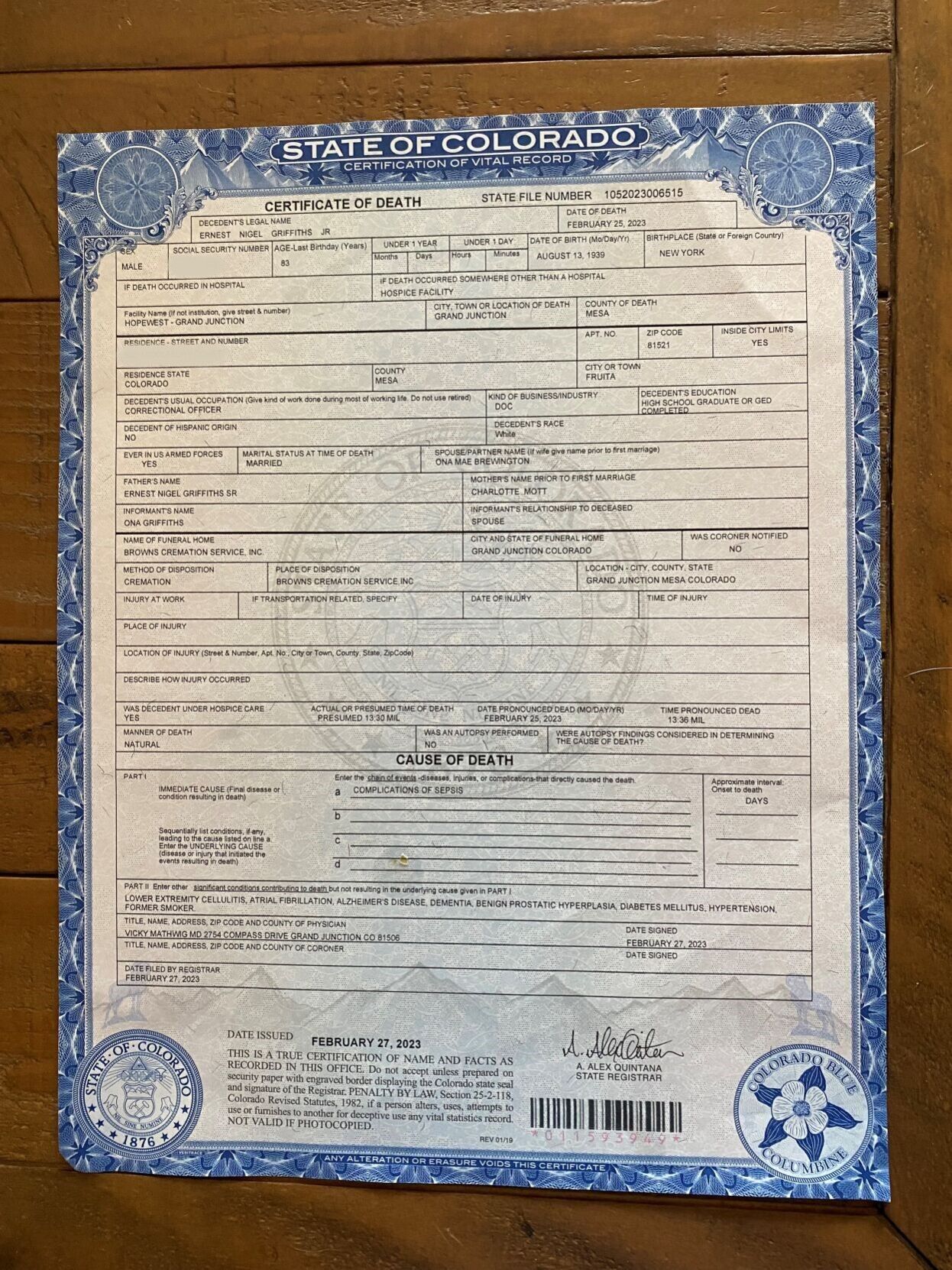

On Feb. 22 Griffiths was moved to a local hospice. There was nothing more that could be done. He died three days later. His death certificate listed the cause as complications of sepsis.

Five months later, on July 27, the Department of Regulatory Agencies sent a letter to Mantey Heights clearing it. “After thorough review and discussion, it was determined that there were insufficient grounds to warrant the commencement of formal disciplinary proceedings as required by the provisions of Colorado law. Accordingly, the Board has dismissed the complaint,” said the letter, which was included in the police report.

On Aug. 9, McCullough wrote in his case summation that while he presented his findings to the Colorado Attorney General’s Office, ultimately “after reviewing all statements and evidence during this investigation, there is currently not enough evidence to charge any specific individual with a crime.”

The case was then closed.

The outcome of the Adult Protective Services investigation is still pending, said Benton. The agency declined to comment, saying its cases are confidential.

Benton told The Gazette he is confident Adult Protective Services, like the other agencies, will clear Mantey Heights.

49 years together

Ernest Nigel Griffiths Jr. was buried March 9 in Section 7, Row O of the Veterans Memorial Cemetery of Western Colorado following a military funeral.

Ernest Griffiths Jr. enlisting is the US Air Force in 1957.

Courtesy

Ernest Griffiths Jr. enlisting is the US Air Force in 1957.

He was stationed in Alaska when he left the service in 1966. In his civilian life, he was an Alaska state trooper, worked for an armored car company, and eventually moved to the Alaska Department of Corrections, where he rose to assistant superintendent before he retired.

It was through his job at the armored-car company that he met a pretty 19-year-old named Ona Brewington, who worked in an accounting office. The women in the office all thought he was cute and made a bet on who could get a date with him. Ona won that bet and, four months later they were married on Feb. 7, 1974. The couple moved to Colorado in 1993.

His death came just a little over two weeks after the couple’s 49th wedding anniversary.

He was a father of five, a grandfather and a great-grandfather. Through the years, he and his wife were foster parents to 50 children, his wife said.

‘Families have been let down’: Colorado’s troubling assisted living deaths stir calls for action

In the months since her husband’s death, Ona Griffiths wrestles with the sadness but also the guilt. She wonders if she could have done more to save him, to be more vigilant.

There is also anger. She has hired Grand Junction lawyer Chadwick McGrady. “It is awful commentary on the services provided when grossly negligent care leads to the wrongful death of our society’s most vulnerable,” he told The Gazette.

Griffiths said several staff members at Mantey Heights called her after her husband’s death. “We loved Griff. We would never have let anything happen to him,” she said she was told, “We did everything we could.”

She hung up, seething.

“There was no reason for him to die the way he did,” Griffiths said recently at her home in Fruita, “Someone had to have seen something and they did nothing.”

This story is part of a continuing series on systemic problems with residential elder care in Colorado and the lack of accountability when things go wrong. If you or a family member had an experience with care given at a senior residential facility or you have worked at one and seen abuse or neglect, contact Jenny.Deam@Gazette.com.

This story was reported through interviews with Ona Griffiths who provided photos and documents, as well as emails and interviews with the VA regional and national offices, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, elder care advocates, and Stellar Senior Living’s leadership. Additional information was gathered through Grand Junction Police Department records, an internal state Adult Protective Services caseworker report, CMS’ nursing home database, ProPublica’s Nursing Home Inspect, and Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment records.