Marijuana industry advocates, critics and regulators reflect on 10-year anniversary of legalization

Oswaldo Barrientos picks dead leaves from marijuana plants at the grow facility where he works near downtown Denver in an April 3, 2019, photo. Colorado banking industry officials say as many as 35 banks and credit unions are quietly offering financial services to legal marijuana businesses in the state even as a bill that would make it easier to allow them to do business with the industry works its way through Congress.

Thomas Peipert / AP

Advocates and critics of the marijuana industry offered contrasting assessments of the drug 10 years after its legalization, with the former calling its decade-long existence a successful model for the rest of America, while the latter insist it has harmed Coloradans.

Voters legalized marijuana use in 2012. Today, the industry has more than 2,500 active cannabis business licenses, including 912 retail establishment licenses. In addition, some 36,000 active occupational licenses have been issued to workers in the industry.

“Colorado’s launch of a regulated adult-use cannabis market was a major inflection point in our nation’s relationship with marijuana. It set a compelling example not only for other states, but also for countries around the globe,” said Mason Tvert, who co-directed the legalization campaign.

Luke Niforatos of Smart Approaches to Marijuana characterized the drug’s legalization as a disaster for the state.

“We have seen an addiction-for-profit industry produce and promote stronger, more addictive drugs in order to maximize their bottom line,” he said. “From increases in traffic fatalities due to impaired drivers to more emergency department visits, Coloradans are being harmed by these drugs. Simply, the legalization of marijuana has not made Colorado a better state to live and raise a family in.”

From the industry’s viewpoint, the legalization has translated to hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue that is directly benefitting governments at all levels.

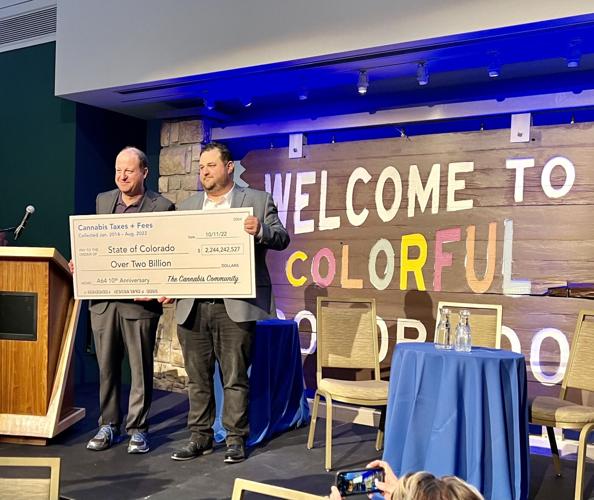

In a statement, Tvert said marijuana sales — which began in 2014, two years after the law’s passage at the ballot box — reached $15.28 billion, while the state collected about $2.6 billion in revenue from taxes and fees. He said local governments additionally earned hundreds of millions of dollars from their own taxes and fees. He noted that Denver, for example, announced in October that it surpassed $500 million in local marijuana tax revenue.

Those revenues went to help fund school construction projects and programs, such as those aimed at improving literacy and dropout rates, preventing bullying, and hiring health professionals, Tvert said. He added that the revenue funded law enforcement and regulation, including efforts to prevent impaired driving and substance abuse, offer treatment, and provide affordable housing grants and loans.

Brian Vicente, a founding partner of the national cannabis law firm Vicente Sederberg, said the “experiment” has clearly been a success.

“Colorado has stopped arresting thousands of people annually, produced tens of thousands of cannabis-industry jobs, and generated more than $2.5 billion dollar of tax revenue for the state,” he said. “Colorado’s leadership on drug policy is clear, and it is once again leading the way with its implementation of the initiative approved by voters last year to decriminalize and regulate psychedelic mushrooms and other natural medicines.”

Critics maintained that the “experiment” fell “short of the industry and advocates’ many lofty promises, including that it would displace the illicit market and uplift communities of color.”

Henny Lasley of One Chance to Grow up said Colorado’s decision to allow THC in an “unlimited array of brightly colored, flavored, highly potent products” which includes edibles, created a “tremendous amount of confusion and made educating around consumption risks…nearly impossible.”

Such risks, Lasley said, include acute psychosis, uncontrolled vomiting, addiction and mental health risks.

“The state hasn’t established a uniform serving size, a maximum amount of THC per package (except for edible products) or limited potency. The industry has not done enough to acknowledge the risks of marijuana use, and the media has played along,” Lasley said, adding that the research supports a growing body of evidence that THC has negative consequences.

Niforatos said policymakers should continue investing in prevention programs, particularly when it comes to use among young people and driving under the influence of the drug.

“We’d also like to see the adoption of potency caps, which have been implemented in other states and would establish an upper bound on the strength of marijuana products. Regulators must continually test products and ensure that dispensaries are not selling to minors,” Niforatos said, adding that law enforcement must keep cracking down on the illicit market, which legalization failed to stamp out.

Meanwhile, advocates, such as the Marijuana Industry Group, said the strict regulations and high taxes on marijuana are dragging the industry into the ground in Colorado.

MIG’s Truman Bradley said Colorado is “killing its own industry with regulation and taxes.”

In Colorado, on top of regular sales tax rates, the marijuana industry pays an excise tax for wholesale marijuana — product before it is sold to customers — and a special sales tax on retail cannabis sales.

In a recent Aurora council meeting, Bradley said taxes on marijuana have gone up roughly twice as fast as sales since cannabis was legalized.

In addition to paying extra in taxes, the marijuana industry is also not allowed to take normal business tax deductions for things it spends money on, such as rent and employee salaries, he said.

Such deductions aren’t allowed for the cannabis industry under something known as Internal Revenue Service regulation 280E. That regulation came into play in the 1970s, when drug dealers were setting up limited liability companies and then deducting their business costs, including drugs, from their taxes. In response, the IRS came up with regulation 280E, which says no deduction or credit shall be allowed for any trade or business if that business traffics in controlled substances under either Schedule I or II of the Controlled Substances Act.

Bradley pointed to several factors causing the decline, such as lack of tourism to Colorado after border states legalized marijuana, inflation and overproduction.

The increase in taxes on the product make it even harder for marijuana businesses to stay solvent, Bradley said.

While the taxes make business harder for licensed marijuana retailers, they make business easier for illicit marijuana sellers, he said.

“As taxes go up, that helps the illicit market because they don’t pay taxes,” Bradley said. “At what price point does someone go from buying at the store to buying from the guy in the alley? We don’t know. But it’s something we worry about if prices go up.”

On a local level, people who oversee regulations to the marijuana industry believe that those regulations have been critically important to Denver’s success with its recreational marijuana rollout.

Molly Duplechian, Denver’s Executive Director of Denver Excise and Licenses, said the city and Colorado are the model for other entities that legalized recreational marijuana.

“We want to see the market thriving and growing but we also balance that with our core focus and role which is protecting public health, safety and welfare,” Duplechian said. “We want to make sure that those protective regulations and measures are in place so we can’t compromise any of those for an increased market.”

Marijuana critics counter that strict regulation is necessary. They also prefer higher taxes as a form of deterrent.

“Strict regulation is absolutely critical for kids and communities,” said Lasley, whose group seeks to “keep kids safe from all the dangers of marijuana commercialization.”

Lasley said despite the reported decrease in youth marijuana use during the pandemic, usage among young people remains “unacceptably high,” particularly when taking into account several factors, such as THC being found in the toxicology screens for individuals ages 10 to 24 who died by suicide and the “statistically significant increase” in the number of kids purchasing directly from dispensaries. Lasley added that nearly 60% of high school students who reported using marijuana in the last 30 days used “highly concentrated THC products such as wax and shatter”

“Philosophically, we have always supported high taxes on marijuana products. Youth are price sensitive and a robust tax structure helps reduce youth use,” Lasley added.

Correction: A comment was incorrectly attributed to Henny Lasley in an earlier version of this article. The comment was from Luke Niforatos.

Reporters Kyla Pearce, Carol McKinley and Luige del Puerto contributed to this article.