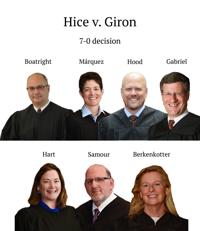

Colorado Supreme Court walks back ruling denying immunity to speeding officer who killed 2

Q29sb3JhZG8gU3VwcmVtZSBDb3VydCBKdXN0aWNlIFdpbGxpYW0gVy4gSG9vZCBJSUkgc3BlYWtzIHRvIHN0dWRlbnRzIGF0IFBpbmUgQ3JlZWsgSGlnaCBTY2hvb2wgZHVyaW5nIGEgQ291cnRzIGluIHRoZSBDb21tdW5pdHkgZXZlbnQgaW4gQ29sb3JhZG8gU3ByaW5ncyBvbiBUaHVyc2RheSwgTm92LiAxNywgMjAyMi4gKFRoZSBHYXpldHRlLCBQYXJrZXIgU2VpYm9sZCk=

UGFya2VyIFNlaWJvbGQ=

The Colorado Supreme Court on Tuesday walked back a ruling by the state’s second-highest court that broadened first responders’ liability for injuries, instead concluding emergency vehicle operators need not activate their lights and sirens during the entirety of a pursuit in order to keep their immunity from lawsuits.

After an Olathe police officer, traveling in excess of the speed limit, slammed into a vehicle and killed the two occupants, the Court of Appeals considered whether governmental immunity barred a wrongful death lawsuit. A three-judge appellate panel looked to the portion of state law that denies immunity when an officer exceeds the speed limit and does not use lights or sirens.

The result was a straightforward, but broad, rule: If an officer in pursuit exceeds the speed limit and fails to use his lights or siren at any point, he is not immune for any injuries he causes.

However, following oral arguments in which the Supreme Court worried officers would face liability for not activating their lights the second they exceed the speed limit, the justices concluded the Court of Appeals went too far in looking at the entirety of a pursuit.

An emergency vehicle driver forfeits their immunity “when a plaintiff’s injuries could have resulted from the driver’s failure to use alerts while speeding in pursuit of a suspected or actual lawbreaker,” clarified Justice William W. Hood III in the court’s Feb. 20 opinion.

In the underlying case, Officer Justin Hice was monitoring traffic along U.S. Highway 50 when he saw a white Toyota exceeding the speed limit. Hice gave chase, which lasted for 36 seconds. He never activated his siren, but turned on his lights for the last five to 10 seconds. At an intersection, Walter and Samuel Giron’s van turned in front of Hice. He hit the van going at least 75 mph.

The Girons’ surviving relatives sued Hice and the town of Olathe. In response, the defendants invoked the Colorado Governmental Immunity Act. Under the law, immunity only applies to emergency vehicles exceeding the speed limit during a pursuit if they are “making use of audible or visual signals.”

The vehicle of Walter and Samuel Giron, who died from their injuries after Olathe Officer Justin Hice collided with them on July 3, 2018. Photo from the appellate brief in Giron v. Hice et al.

The vehicle of Walter and Samuel Giron, who died from their injuries after Olathe Officer Justin Hice collided with them on July 3, 2018. Photo from the appellate brief in Giron v. Hice et al.

Montrose County District Court Judge D. Cory Jackson initially dismissed the lawsuit after finding Hice used his emergency lights and did not create an unreasonable risk of injury in his pursuit. Jackson credited the testimony of current and former police officers over the motorists who Hice passed at high speed and who came close to crashing into Hice themselves.

Then, a Court of Appeals panel reinstated the lawsuit, finding it did not matter that Hice turned on his lights in the final seconds before impact.

“For Officer Hice and Olathe to be entitled to immunity, Officer Hice would need to have activated his emergency lights or sirens the moment he exceeded the speed limit during his pursuit,” wrote Judge Sueanna P. Johnson.

On appeal to the Supreme Court, multiple outside groups weighed in. The Colorado State Patrol contended courts should not second-guess the “split second decisions” of first responders. The Colorado Trial Lawyers Association countered the Court of Appeals’ rule would only be a problem for emergency personnel who break the law.

The defendants, meanwhile, warned the Court of Appeals’ rule could apply in absurd situations: eliminating immunity if an officer fails to activate his lights for one second at the beginning of a pursuit when he is traveling 1 mph above the speed limit, even if his lights are on the entire time afterward.

“Each side has done a pretty good job of conjuring hypotheticals that make the other side’s position look a little silly and extreme,” Hood observed during oral arguments. “It doesn’t seem so unreasonable to me to ask police officers, particularly when they are doing this kind of patrol duty, to at least activate their lights as soon as they’re going to engage someone who’s speeding. They know that they’re gonna have to speed in order to catch up.”

Ultimately, Supreme Court rejected the Court of Appeals mandate that first responders activate lights or sirens for the entirety of a pursuit.

“This interpretation means emergency drivers waive immunity even when there’s no possible connection between the failure to use emergency alerts and the plaintiff’s injuries,” Hood noted.

The justices returned the lawsuit to the Court of Appeals to determine whether Hice’s failure to activate his lights until the final seconds “could have contributed” to the crash. The court also directed the appellate panel to analyze whether Hice’s actions endangered life or property, which is another basis for forfeiting immunity.

The case is Hice et al. v. Giron et al.