Got space junk? Colorado companies have solutions

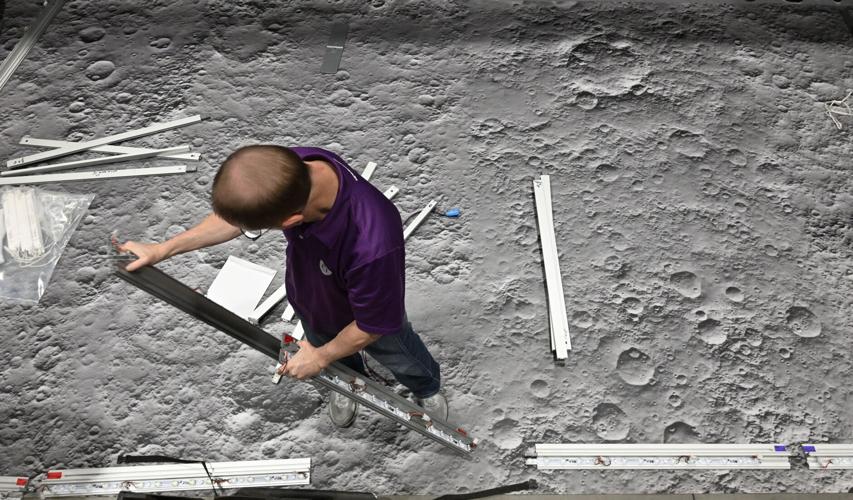

Installation technician Rebecca Servo with Momentum Management looms over the Earth as she installs part of a display for the 39th Space Foundation Space Symposium on Sunday, April 7, 2024. The Broadmoor Hotel was a beehive of activity to get ready for the over 10,000 attendees for the symposium from around the world.. (Photo by Jerilee Bennett, The Gazette)

Space junk — NASA estimates 9,000 metric tons of it — is orbiting the Earth, posing a risk to the grand plans for an on-orbit business ecosystem.

While the threat of collision is still relatively low, when it happens it can destroy a satellite. In 2009, an inactive Russian satellite hit a working communication satellite and both exploded.

As one of the biggest problems for the space industry, it will no doubt capture attention again at the 39th Space Symposium this week in Colorado Springs, where 12,000 industry members will gather. For at least some, the junk is an economic opportunity.

Colorado-based companies are working on a variety of solutions such as capturing the junk, remanufacturing it and devising ways to extend the life of satellites, such as jetpacks and on-orbit fuel delivery services.

Removing or remanufacturing space junk will ensure more safety for an on-orbit ecosystem of warehouses, foundries and manufacturers that will help accelerate the plans to go to Mars, explained Ron Lopez, president and managing director of Denver-based Astroscale. He expects it will be cheaper to manufacture items in space, in part because it will cut out the cost of launch.

At the same time, the industry is moving away from satellites the size of school buses expected to last decades to much smaller and cheaper satellites that are adopting designs for refueling.

For decades, engineers have designed satellites to carry all the fuel they would ever need.

“Imagine buying a car with 15 years of fuel,” explained Daniel Faber, CEO and co-founder of Lafayette-based Orbit Fab. “…You end up trying not to move your car at all.”

The Space Force wants to move past those constraints, saying in a news release that achieving on-orbit refueling would be similar to the 1950s advancement of refueling planes while flying, which improved flexibility for pilots and the entire structure of the military.

Many satellite operators that would benefit from the additional flexibility of refuelable satellites work in Colorado Springs, a town known for its space traffic control services.

A circular space economy

Space Force, the youngest military branch, invested last year in a collaborative project to gather up large pieces of junk, such as defunct satellites and old rocket bodies, and remanufacture the aluminum into fuel.

In the long term, Astroscale plans to use docking plates similar to tow-truck hooks to capture big items. Small debris is a threat in space, but it does not offer the same value.

“The focus right now needs to be on the large intact objects that can be docked with safely,” Lopez said.

The company took a step forward in its debris removal work in February with the launch of a satellite set to inspect a rocket body to collect observational data to help inform removal work. The satellite will not remove the object as part of this mission.

Loveland-based CisLunar is working on how to reforge aluminum from space junk into wire for on-orbit manufacturing and solid-state fuel rods.

“If we can turn that debris into a resource, it becomes more of a mining problem,” said Gary Calnan, CEO and co-founder of CisLunar.

For the company, fuel is a good first product because it can still be used even with impurities and it fulfills the need to improve space mobility, he explained.

One of the challenges with forging metal in space is the loss of enough gravity to cast shapes. The company is planning to use electromagnetic induction in its forging process to guide the metal.

The company has tested its system in parabolic flight and has additional testing planned.

Astroscale and CisLunar are working with Neumann Space, an Australian-based company that tested a solid-metal thruster on orbit in December.

Gassing up in space

Rather than sending up “preordained junk,” Orbit Fab’s Faber said he expects companies will shift to refuelable satellites; his company is ready to supply gas ports and plans to deliver the gas as well.

In March, regulators cleared Orbit Fab’s fueling ports, branded Rapidly Attachable Fluid Transfer Interfaces, for space flight and the company expected to start shipping them right away.

Three Space Force Tetra-5 program satellites, developed specifically to test on-orbit refueling, will have the new fueling port for a planned demonstration next year, according to a news release.

Faber said he expects refuelable satellites would change the industry just as reusable rockets did, and companies who do not adopt the trend will likely not make it.

Greater fuel for greater mobility is also a key component for a contested space environment, he said.

“You will not win if you do not have mobility,” he predicted.

Jetpacks in space

Astroscale is working on a satellite it calls Life Extension In-Orbit, or LEXI, that would attach to older satellites and maintain their position in orbit, like a jetpack. It could give several more years of life to satellites worth hundreds of millions, Lopez said.

Some larger and older satellites are more than 22,000 miles from the Earth and stay in a fixed position. LEXI would dock with an older satellite and keep it in place and make course corrections. In this case, the boost could literally keep the satellite from the graveyard, an orbit farther out into space.

Orbit Fab expects to refuel the satellites used as jetpacks as well, Faber said.

At Space Symposium this week, the Space Foundation’s CEO Heather Pringle expects to see collaboration to solve space’s biggest challenges. The Space Foundation is expecting people from 1,500 companies who can help break down tough problems, like junk, to ensure the $546 billion industry can keep growing.

And to keep all the services enabled by space — every banking transaction and GPS mapped trip — functioning.

“It underpins so many aspects of our lives,” Pringle said.