Appeals court overturns woman’s conviction, finds defect in template jury instructions

Colorado’s second-highest court overturned a criminal conviction from La Plata County on Thursday, concluding it was the “rare case” in which the template jury instructions incorrectly describe how jurors can find someone guilty of retaliating against a witness.

The jury that convicted Erin Amber Trujillo was instructed it could find her guilty if she directed threats or harassment toward a likely witness in a criminal proceeding, and that she acted intentionally. The instructions tracked the template issued by the Colorado Supreme Court that contains suggested language for criminal trials.

However, a three-judge panel for the Court of Appeals determined the template was wrong. In a small but crucial distinction, Judge Katharine E. Lum wrote that the current wording does not require jurors to specifically find a defendant intended to retaliate because of the target’s status as a witness.

“The problem is that these instructions, even when read together, did not inform the jury that the retaliation or retribution must be because of the witness’s or victim’s status,” she wrote in the Feb. 27 opinion. “Thus, the instructions could have led the jury to convict even if Trujillo’s retaliatory conduct was motivated by something other than the witness’s or victim’s ‘relationship to a criminal proceeding.'”

In the underlying case, Trujillo’s son and his ex-girlfriend — who would become the alleged victim in Trujillo’s criminal proceedings — were driving together when an argument ensued. The son threw the victim’s cell phone out the window and the victim threw out the son’s wallet. The victim then exited the vehicle at a stoplight.

In response to the victim’s phone call, a sheriff’s deputy stopped Trujillo’s son. The deputy then arrested the son on suspicion of false imprisonment and criminal mischief. Trujillo arrived shortly afterward and told law enforcement her son was “attacked,” “being abused,” and she was “pressing charges against everybody.”

The victim, meanwhile, retrieved her vehicle and met up with her mother at a gas station. The two of them drove to the sheriff’s office, but Trujillo began following closely behind them. Once at the police station, Trujillo pulled nearby and said, “Where is (her son’s) wallet, or I’m going to beat your ass.” The victim was speaking on the phone with police at the time about Trujillo, but she allegedly felt scared by the comment.

Prosecutors subsequently charged Trujillo with retaliating against a witness or a victim.

The defense proposed a jury instruction that tracked a 1999 Colorado Supreme Court decision. There, the court clarified that committing witness retaliation required “the specific intent to retaliate or to seek retribution against a person protected by the statute because of that person’s relationship to a criminal proceeding.”

The Ralph L. Carr Colorado Judicial Center in downtown Denver houses the Colorado Supreme Court and Court of Appeals. (Michael Karlik/Colorado Politics)

Michael Karlik/Colorado Politics

The Ralph L. Carr Colorado Judicial Center in downtown Denver houses the Colorado Supreme Court and Court of Appeals. (Michael Karlik/Colorado Politics)

Instead, District Court Judge Suzanne F. Carlson gave an instruction based on the state’s template language for jury trials. The instructions asked jurors to consider whether Trujillo retaliated against a witness, and also whether she intended to cause “the specific result” of retaliation. The jury found Trujillo guilty of the lesser offense of attempted intimidation.

On appeal, Trujillo noted her intent was the central dispute. In other words, did she retaliate against the victim because she was a witness, or because Trujillo simply wanted the son’s wallet back?

“She did not say, ‘You’re gonna pay for calling the police.’ She didn’t say, ‘Don’t you dare testify against my son’,” public defender Emily Hessler told the Court of Appeals panel during oral arguments. “It had nothing to do with the criminal proceedings.”

Meanwhile, the government argued Trujillo’s jury necessarily convicted her of intentionally retaliating against the victim because she was a victim.

“It’s not just an act of revenge against somebody. It’s a specific nexus to the fact that they’re a victim or a witness,” said Senior Assistant Attorney General Grant R. Fevurly.

But the appellate panel believed the jury, in reading the instruction, could have found Trujillo guilty of intentionally retaliating against the victim, but not necessarily because she was a victim.

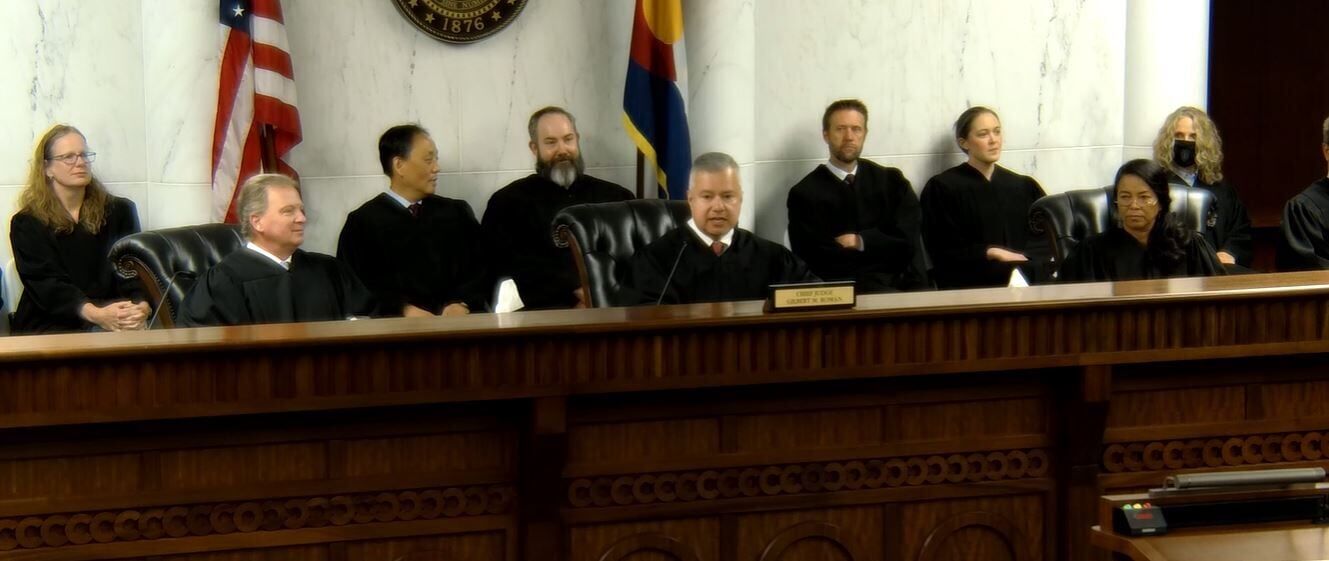

FILE PHOTO: Members of Colorado's Court of Appeals gather at the ceremonial swearing-in of Judge Grant T. Sullivan.

image from video

FILE PHOTO: Members of Colorado’s Court of Appeals gather at the ceremonial swearing-in of Judge Grant T. Sullivan.

“For example, a person who sees a crime victim steal her parking spot outside the courthouse and then harasses the victim as retaliation for the parking spot theft does not commit the crime of retaliation against a witness or victim,” wrote Lum, “because the retaliation was for the taking of the parking spot, not for the victim’s ‘relationship to a criminal proceeding’.”

She added it was “a very close call,” but in the absence of precise language, jurors could have convicted Trujillo solely because she was upset the victim threw her son’s wallet out of a moving car.

This was “a rare case where the model instructions for retaliation and intent don’t adequately inform the jury of the law,” Lum concluded.

The panel ordered a new trial for Trujillo.

The Court of Appeals also briefly touched upon Trujillo’s argument that the witness retaliation law unconstitutionally criminalized her protected speech. Trujillo cited a recent U.S. Supreme Court decision about Colorado’s stalking law, Counterman v. Colorado, which now requires prosecutors to prove an alleged stalker’s intent in communicating with their victim.

Lum wrote that the panel had no opinion about whether Trujillo’s comments to the alleged victim were true threats not protected by the First Amendment, but she noted the trial judge must decide that question before proceeding with a second jury trial.

The case is People v. Trujillo.