Colorado justices mull lawsuit over fossil fuel producers’ liability for alleged local climate change harms

Members of the Colorado Supreme Court considered on Tuesday whether to permit Boulder County and the city of Boulder to seek damages against two oil and gas producers for the harms they allegedly caused over multiple decades by concealing and misrepresenting the dangers of climate change.

Although the lawsuit is the first of its kind to reach the state’s highest court, the case has already wound its way through every level of the federal court system and resembles litigation that courts around the country have already considered.

The local governments’ claims implicate a variety of political and policy questions, including the executive and legislative branches’ prerogative to set energy policy and the slippery slope of permitting every municipal government to potentially seek money from private entities for climate-related disasters.

But the legal question during oral arguments was straightforward: Can the plaintiffs even rely on state law in the first place to seek localized damages for localized climate change injuries?

“This is Boulder. Some other county in another state could bring another lawsuit and if they recover a large verdict, that’s gonna change their behavior. That’s gonna change policy,” said Justice Carlos A. Samour Jr. “So, how do we deal with that?”

Colorado Supreme Court Justice Carlos A. Samour Jr. speaks to students at Pine Creek High School during a Courts in the Community event in Colorado Springs on Thursday, Nov. 17, 2022. (The Gazette, Parker Seibold)

Parker Seibold

Colorado Supreme Court Justice Carlos A. Samour Jr. speaks to students at Pine Creek High School during a Courts in the Community event in Colorado Springs on Thursday, Nov. 17, 2022. (The Gazette, Parker Seibold)

Compensation for injuries

In the plaintiffs’ telling, the defendants — ExxonMobil and Suncor — knew for decades that the burning of fossil fuels and the release of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere would change the planet’s climate. Yet, the companies misrepresented or concealed their internal findings from the public. As a result, Boulder County and the city of Boulder have had to spend money to address droughts, wildfires and other manifestations of extreme weather, the plaintiffs argued.

The plaintiffs brought claims of trespass, nuisance and civil conspiracy under the state’s common law — which refers the longstanding category of civil claims that does not originate with a specific statute. To them, the lawsuit was not about regulating emissions or altering federal policy, but to use the same tools as plaintiffs who are harmed by faulty products, for example.

On their side, the local governments wielded a 2023 decision of the Hawaii Supreme Court, finding the city of Honolulu’s similar state-law claims against Sunoco and other defendants could proceed. Last month, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to review that decision. The outgoing Biden administration submitted a brief in support of Honolulu, arguing the claims should proceed even if the evidence later shows federal law blocks the energy companies’ liability for specific acts.

Federal or state court?

Meanwhile, the defendants in the Boulder County case leaned on a different decision out of the New York-based U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. In that lawsuit, where New York City sued ExxonMobil and other energy corporations, the Second Circuit ruled that the city would be “jeopardizing our nation’s foreign policy goals” by deploying state-level legal claims against longstanding national and international energy agreements.

As a result, the defendants in Colorado emphasized the federal government’s precedence over climate policy. Legally, they argued the federal common law would have once been the tool for a pollution-related lawsuit, but the Clean Air Act has since come into play. And because the Clean Air Act does not provide grounds for the local governments to sue, they cannot proceed with their state-level claims.

Last year, Boulder County District Court Judge Robert R. Gunning allowed many of the local governments’ claims to proceed against ExxonMobil and two subsidiaries of Calgary-based Suncor. He noted the plaintiffs would be left “without legal recourse” if the energy companies’ argument were true. Moreover, he observed even the federal courts thought the lawsuit should be in state court.

Although Boulder County and the city of Boulder filed their claims in 2018, ExxonMobil and Suncor transferred the case to federal court. But a trial judge and the Denver-based 10th Circuit believed it did not belong in the federal system, and the U.S. Supreme Court declined to take up the appeal in 2023.

“As the Local Governments aptly put it,” wrote Gunning, “the Energy Companies are arguing against a case the Local Governments did not plead. Through this action, the Local Governments are not attempting to litigate a policy solution to global climate change, limit fossil fuel use or production, or control greenhouse gas emissions.”

Now before the state Supreme Court, ExxonMobil and Suncor maintained the subject matter was “not a traditional area of state regulation.”

The local governments “are seeking to recover from the effects of greenhouse gas emissions worldwide, whether or not Exxon and Suncor were responsible for them,” argued attorney Kannon K. Shanmugam.

He added that the legislative process was the appropriate way to regulate greenhouse gas emissions.

“I have the same concern — every city in the country brings this case, it feels like regulation,” said Justice Richard L. Gabriel. “But where is the line between regulating the emissions and a damages claim?”

No explicit prohibition

Marco Simons, representing the plaintiffs, argued that no constitutional provision or federal law prohibited Boulder County and the city from attempting to hold the defendants liable for their injuries.

“There is a feeling that this is something that should be regulated by federal law,” said Gabriel.

“Some ‘feeling’ that federal law really should control is not enough,” responded Simons.

“What troubles me is it’s not asking to regulate conduct in another state, but it’s to punish conduct that happened in another state,” interjected Justice Brian D. Boatright. “Can you help me understand how Boulder gets to be compensated for conduct that happened maybe on the other side of the world?”

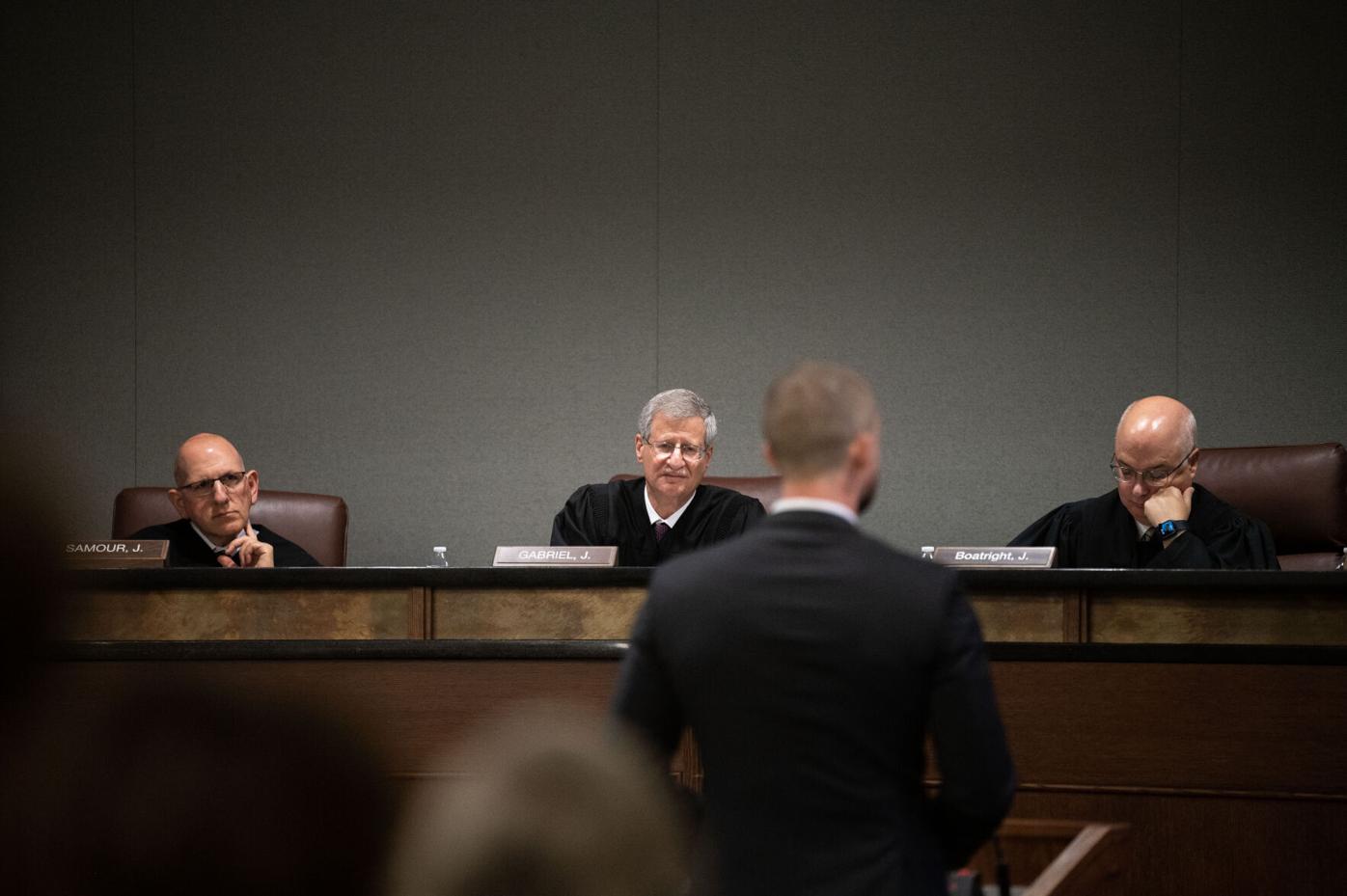

Colorado Supreme Court Justices (from left) Carlos A. Samour Jr., Richard L. Gabriel and Brian D. Boatright listen to arguments from Jake Davis, an attorney in the Nonhuman Rights Project v. Cheyenne Mountain Zoological Society case, as part of Courts in the Community at the Wolf Law building at University of Colorado Boulder on Thursday, Oct. 24, 2024. The semi-annual event entails the Colorado Supreme Court hearing arguments before an audience of students throughout the state. (Stephen Swofford, Denver Gazette)

Stephen Swofford Denver Gazette

Colorado Supreme Court Justices (from left) Carlos A. Samour Jr., Richard L. Gabriel and Brian D. Boatright listen to arguments from Jake Davis, an attorney in the Nonhuman Rights Project v. Cheyenne Mountain Zoological Society case, as part of Courts in the Community at the Wolf Law building at University of Colorado Boulder on Thursday, Oct. 24, 2024. The semi-annual event entails the Colorado Supreme Court hearing arguments before an audience of students throughout the state. (Stephen Swofford, Denver Gazette)

Simons clarified that the plaintiffs are not seeking to hold ExxonMobil and Suncor liable for all the harms they allegedly caused, but solely for the impacts locally.

Justice Maria E. Berkenkotter asked Shanmugam whether the state Supreme Court should “read too much into” the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to not intervene in the related Hawaii lawsuit. Shanmugam suggested the Supreme Court’s decision to let that case proceed could simply be a desire to let lower courts develop the issues further before hearing such a case itself.

The state Supreme Court also received written briefs from a variety of interested parties. The advocates included environmental law professors who urged the court not to recognize a loophole “where polluters can circumvent accountability,” as well as the Chamber of Commerce, which emphasized the need for a “uniform approach” to greenhouse gas emissions.

Justice Melissa Hart did not attend the arguments due to illness. Chief Justice Monica M. Márquez said Hart “will be participating in the decision.”

The case is County Commissioners of Boulder County et al. v. Suncor Energy USA, Inc. et al.