Colorado Supreme Court questions 2020 change to child neglect laws

RklMRSBQSE9UTzogRnJvbSBsZWZ0LCBDb2xvcmFkbyBTdXByZW1lIENvdXJ0IEp1c3RpY2VzIFdpbGxpYW0gVy4gSG9vZCBJSUksIE1lbGlzc2EgSGFydCBhbmQgTWFyaWEgRS4gQmVya2Vua290dGVyIGxpc3RlbiB0byBhbiBhcmd1bWVudCBkdXJpbmcgYSBDb3VydHMgaW4gdGhlIENvbW11bml0eSBzZXNzaW9uIGhlbGQgYXQgUGluZSBDcmVlayBIaWdoIFNjaG9vbCBpbiBDb2xvcmFkbyBTcHJpbmdzIG9uIFRodXJzZGF5LCBOb3YuIDE3LCAyMDIyLiAoVGhlIEdhemV0dGUsIFBhcmtlciBTZWlib2xkKQ==

UGFya2VyIFNlaWJvbGQvR2F6ZXR0ZQ==

The Colorado Supreme Court pondered on Tuesday what the legislature meant to happen when it changed the state’s child neglect laws in 2020 to require more than a positive drug test at birth to deem a child neglected.

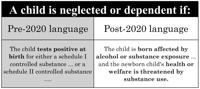

The debate centered on the wording lawmakers chose to replace the previous condition that a child is neglected when he or she “tests positive at birth” for a controlled substance. Now, the child must be “born affected by alcohol or substance exposure” and the “health or welfare is threatened by substance use.”

Some justices, however, wondered if a positive test result by itself could satisfy the “born affected by” provision.

“If I get drunk enough that I have alcohol in my bloodstream at a level that is above legal limits, I have been ‘affected by’ alcohol use. Actually, even if I have alcohol in my blood that is below legal limits, I have been affected by alcohol use,” observed Justice Melissa Hart.

Justices Carlos A. Samour Jr., Melissa Hart and Richard L. Gabriel attend Gov. Jared Polis' 2025 State of the State address on Thursday January 9, 2025 at the Colorado State Capitol. Special to Colorado Politics/John Leyba

John Leyba

Justices Carlos A. Samour Jr., Melissa Hart and Richard L. Gabriel attend Gov. Jared Polis’ 2025 State of the State address on Thursday January 9, 2025 at the Colorado State Capitol. Special to Colorado Politics/John Leyba

Previously, the state’s Court of Appeals interpreted the phrase to require the government to demonstrate some specific health or developmental issue in order to say a newborn has been affected by drug exposure. Hart worried that if the government cannot prove a child has concretely been affected by substances, courts will never reach the related question of whether the child’s health or welfare “is threatened by” a parent’s drug use.

“Whether it’s an adult where you have alcohol in your blood system — whether you’re an adult or a newborn, frankly,” she said, “once your body functions have the substance in them, your body functions are affected.”

During the legislative debate five years ago over Senate Bill 28, which contained the amended substance exposure language, multiple witnesses spoke about the reasons for moving away from a positive drug test alone as a trigger for child neglect.

Changes made by Senate Bill 20-28

Changes made by Senate Bill 20-28

“The change in the children’s code is intended to decrease fear and stigma that parents would have in sharing they used substances during their pregnancy, to make it that much easier to get engaged and get involved in the services they’ll need long-term,” testified Jade Woodard of Illuminate Colorado.

Two years after the bill was enacted, El Paso County moved to declare a child, identified as B.C.B., neglected after he tested positive for methamphetamine at birth and his mother had a history of substance use. A jury heard evidence from three pediatricians that meth exposure in the womb can impair cognitive and behavioral skills later in a child’s life, but the experts otherwise testified B.C.B. was healthy.

The child’s father moved to end the case in his favor, arguing the county failed to establish B.C.B. suffered negative effects from the mother’s drug use. El Paso County responded that the meth exposure “puts him at risk for later complications that will manifest in the next few years.” District Court Judge Jessica Curtis denied the father’s motion and the jurors deemed B.C.B. neglected — a step that can lead to the termination of the parent-child relationship.

On appeal, B.C.B.’s parents challenged the idea that the evidence supported a finding of neglect. By 2-1, a three-judge Court of Appeals panel deemed the evidence insufficient under the new standard.

Although the pediatricians testified there would be risks later in B.C.B.’s life, “none of the physicians was able to predict whether the child would actually suffer from these effects,” Judge Matthew D. Grove wrote for himself and Judge Grant T. Sullivan. “An adjudication cannot be premised on conjecture or speculation.”

Colorado Court of Appeals Judge Matthew D. Grove speaks with Morgan Rasmussen and Brisais Vargas, 17-year-old juniors. STRIVE Prep — RISE school in Green Valley Ranch hosted a Courts in the Community event, featuring oral arguments before a three-judge panel with the Colorado Court of Appeals on Tuesday, April 19, 2022. Photo by Steve Peterson

Courtesy of Steve Peterson

Colorado Court of Appeals Judge Matthew D. Grove speaks with Morgan Rasmussen and Brisais Vargas, 17-year-old juniors. STRIVE Prep — RISE school in Green Valley Ranch hosted a Courts in the Community event, featuring oral arguments before a three-judge panel with the Colorado Court of Appeals on Tuesday, April 19, 2022. Photo by Steve Peterson

Judge Terry Fox took a different view of the current law. The fact that B.C.B. did not have “the more pronounced and immediate signs of distress” was not the end of the road for her. She argued that the majority’s interpretation meant a parent could actively use meth throughout pregnancy, “but if the child was not born prematurely, did not have immediate, detectable growth impairments, or was not experiencing withdrawal symptoms, the child would not be a dependent or neglected child.”

Several outside entities weighed in to the Supreme Court on appeal. The Office of the Child’s Representative acknowledged the legislature wanted to eliminate the trigger of a positive drug test alone, but did not believe lawmakers intended to avoid “any consideration of future harm to the child.” Meanwhile, the Office of Respondent Parents’ Counsel and various health advocacy groups endorsed the majority’s view that the state must prove actual harm.

Pregnancy Justice, a nonprofit based in New York City, argued that a focus on hypothetical risks based on prenatal drug exposure would be a slippery slope to “fetal personhood,” a concept Colorado voters have rejected in the past.

Josi McCauley, the legal representative for B.C.B., told the Supreme Court that in her view, a positive test result could still be enough to show a newborn has been affected by substance use, even with the 2020 change.

A positive test could be “merely the threshold for this secondary, larger analysis of whether this child truly is threatened by substance use,” she continued.

“I’m still deeply concerned by your position that a mere positive test meets the first prong,” responded Chief Justice Monica M. Márquez. “I worry about that only because the legislature chose not to use that language, ‘positive test.’ And yet you’re saying the words they did choose — ‘affected by’ — is met by a positive test.”

Justice Maria E. Berkenkotter observed the 2020 change actually broadened the potential for a child neglect determination by moving away from one specific metric — a test for controlled substances — and replacing it with an open-ended assessment of whether a newborn is affected by drugs. She also pointed out the current law does not even require children to be “adversely” affected.

“I’ve been reflecting on what the legislature was trying to do,” Berkenkotter said. “That, in a certain way, is a widening of the net, not a narrowing.”

Justice Carlos A. Samour Jr. did not attend the arguments. Márquez said Samour “is unable to be here today,” but that he will participate in the decision.

The case is People in the Interest of B.C.B.