Divided Colorado Supreme Court: Grandparents no longer ‘grandparents’ after grandchildren’s adoption

The Colorado Supreme Court ruled on Monday that a child’s grandparents are no longer legally “grandparents” who are able to seek visitation once their grandchild’s adoption has been finalized to a new set of parents.

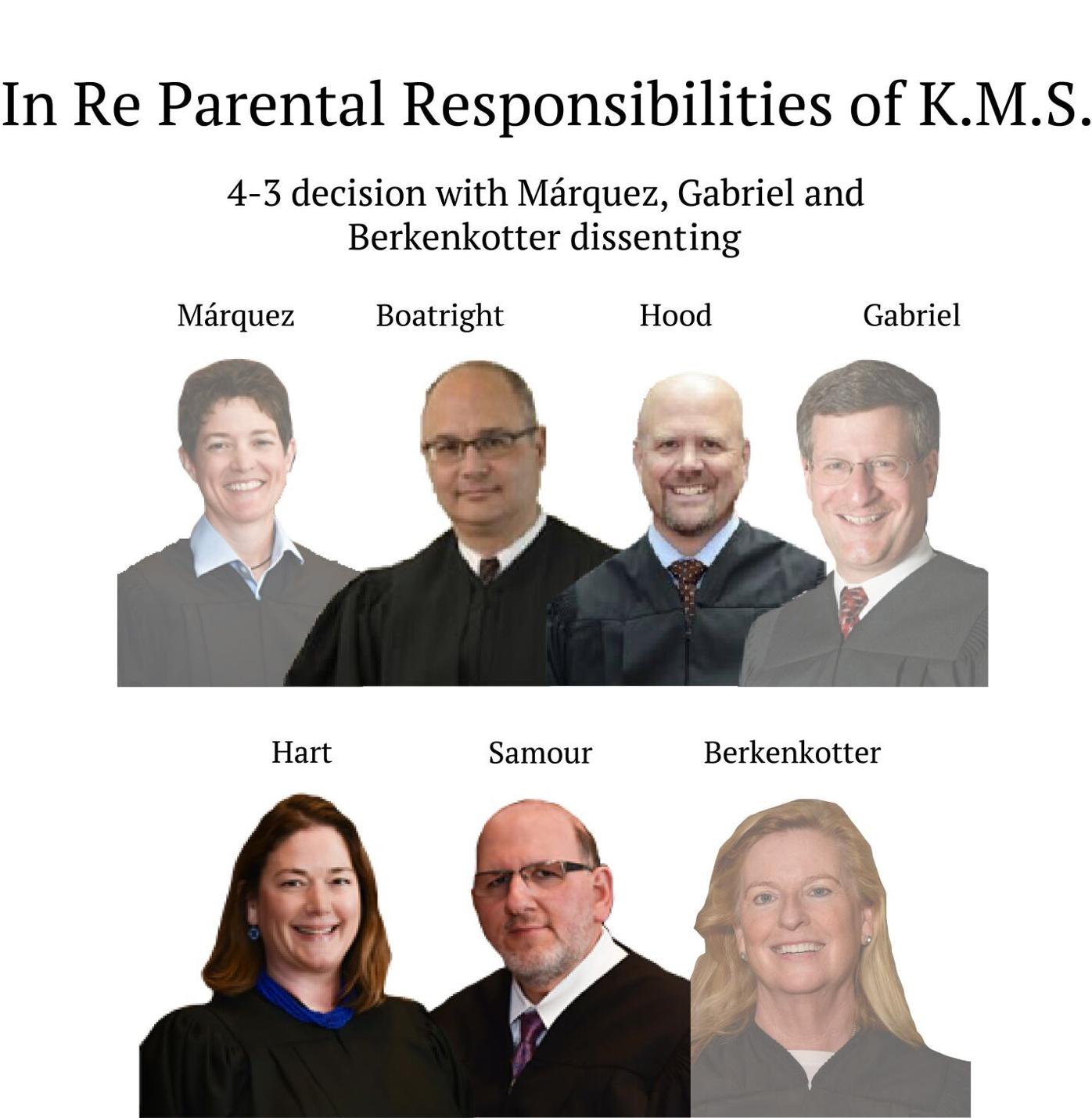

By 4-3, the court concluded the law enabling grandparent visitations applies to a person who “is the parent” of a child’s mother or father. Therefore, if the parents are deceased and a new set of parents has adopted the children, the grandparents no longer fit the definition of grandparents.

“To be sure, the death of a parent does not instantly nullify grandparentage. Yet, an adoption does just that,” wrote Justice Brian D. Boatright in the majority’s June 9 opinion. “We therefore find that standing to seek grandparent visitation is limited to one who is the present parent of a child’s father or mother.”

Justice Maria E. Berkenkotter disagreed with that reasoning, believing Colorado law does not render people grandparents so long as their own children — the parents of their grandchildren — are alive.

“Moreover, a biological parent is a parent in life and in death. That is, when a child loses a parent, whether the child is three or fifty-three, their parent remains their parent forever,” she wrote for herself, Chief Justice Monica M. Márquez and Justice Richard L. Gabriel.

The dispute over the status of grandparents stemmed from the deaths of Brandon and Amanda Sullivan in their Delta County home in April 2020. They left behind three young children. Authorities deemed it a murder-suicide.

A judge appointed the children’s maternal grandparents, Suzanne Nicolas and August Nicolas, as the permanent guardians, while allowing the paternal grandparents to visit. In October 2021, the Nicolases adopted the children.

The paternal grandparents, Jayne Mecque Sullivan and Daniel Francis Sullivan, then petitioned for ongoing visitations, and the judge set a schedule.

However, the Nicolases identified “profound disagreements” between the two sets of grandparents stemming from the slaying. Consequently, they sought to overturn the trial judge’s visitation order for the Sullivans. The Nicolases maintained they were now the children’s parents and the Sullivans, not being the parents of the Nicolases, no longer fell under the definition of “grandparents.”

Previously, a three-judge panel for the Court of Appeals sided with the Sullivans, concluding grandparent visitation rights are not “automatically cut off” whenever a grandchild is adopted because of a provision enabling grandparents to seek visitation upon the death of a parent.

The Sullivans “fall within the definition of grandparents, regardless of when they filed their petition for grandparent visitation,” wrote Judge W. Eric Kuhn.

FILE PHOTO: Judge W. Eric Kuhn speaks following his swearing-in ceremony to the Court of Appeals on July 22, 2022. Also pictured, from left to right, are Judges Rebecca R. Freyre, Craig R. Welling and Ted C. Tow III, and Chief Judge Gilbert M. Román.

The Denver Gazette

FILE PHOTO: Judge W. Eric Kuhn speaks following his swearing-in ceremony to the Court of Appeals on July 22, 2022. Also pictured, from left to right, are Judges Rebecca R. Freyre, Craig R. Welling and Ted C. Tow III, and Chief Judge Gilbert M. Román.

During oral arguments in April, Gabriel asked about a situation in which two parents die in a car accident and a family friend adopts the children.

“In your view, all the grandparents would be out of luck. They’d be out of those children’s lives,” he told Sean Connelly, the attorney for the Nicolases.

“I would hope that in an ideal world, people would say, ‘We want the grandparents still involved in their lives,'” Connelly said.

“I think your answer has to be ‘yes,'” interjected Berkenkotter, that the grandparents could no longer legally seek visitation.

Yes, that is what would happen, Connelly said.

Ultimately, the majority concluded the Sullivans were no longer the children’s grandparents once the Nicolases adopted them.

“We recognize that this loss, and the uniquely difficult circumstances that surround it, present profound challenges for those involved, for which there is almost assuredly no satisfactory legal outcome. Despite this, we must rule for one party and against the other,” wrote Boatright. “Therefore, we determine that the statute’s plain language imposes a temporal limitation, restricting ‘grandparent’ to one who is a grandparent at the time the petition for visitation is filed.”

Berkenkotter argued that lawmakers intended for grandparents whose own children had died to be able to seek visitation with their grandchildren “at any time.” In her view, the Sullivans remained grandparents notwithstanding the adoption.

“That is not to take anything away from the adoptive parent, who is also a parent. It’s simply that the relationship between the parent who died and the child who survived transcends time in a way our language reflects,” she wrote. “We refer, for example, to our deceased family members even if they died decades ago as ‘my father’ and ‘my mother,’ not ‘my former father’ and ‘my former mother.'”

Timothy J. Eirich, who represented the Sullivans, said trial judges may be “reluctant” to grant adoptions in similar cases going forward if it means grandparents will cease to legally be grandparents.

“This is obviously a disappointing outcome on a lot of levels and, as noted by the dissenting opinion, one clearly not intended by Colorado’s General Assembly,” he said. “I expect this issue will require now require a legislative fix.”

Connelly, the attorney for the Nicolases, declined to comment.

The case is In re the Parental Responsibilities of K.M.S. et al.