Hot 100: A late father recounts his life in bullet points

It was, by literal definition, a once-in-a-century opportunity – and obligation: On Monday, my father, Ralph Moore, a hall-of-fame sports writer for The Denver Post, would be turning 100 years old from the great beyond.

As Willy Loman says in “Death of a Salesman”: Attention must be paid.

On July 6, the day before three generations of Moores would gather at Fort Logan to hoist a flask of Jameson and re-tell tales that grow taller by the year, I descended to the crawl space and pulled out “The Ralph Box.” It’s a chest I‘ve pored over dozens of times since Dec. 8, 1997. The date that death, with absolutely no sense of fairness, timing or good drama, took my father – just six agonizing weeks before he would have witnessed (first-hand) his beloved, long-suffering Denver Broncos win their first Super Bowl.

When that day came, I was the Deputy Sports Editor at the Denver Post, where professional decorum forbade overt cheering in the newsroom. (My father had once said he’d prefer I‘d joined the Merchant Marines than follow him into the rough-and-tumble world of sports journalism. I didn’t listen. Neither did my nephew, Bryan, who was an entry-level sports clerk at the time.)

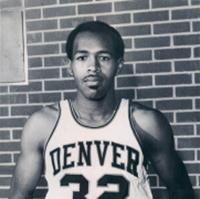

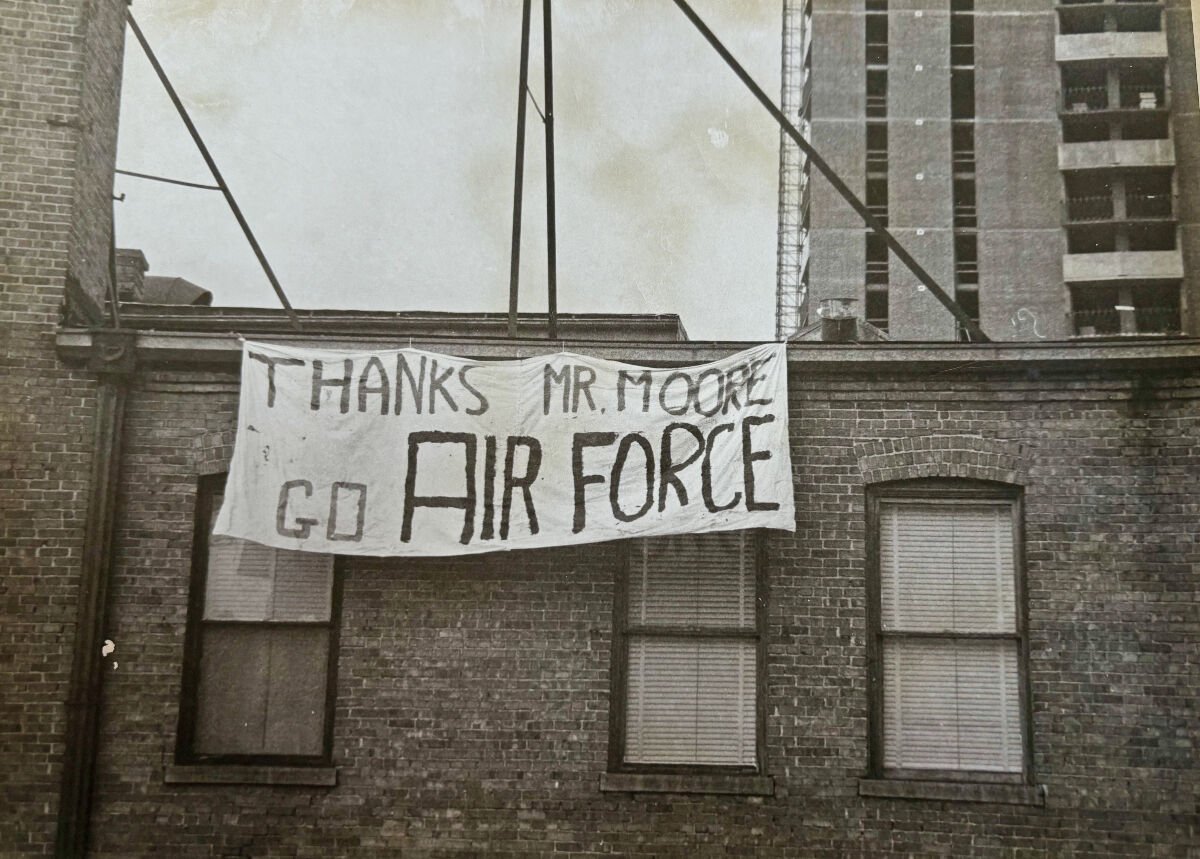

Late sports writer Ralph Moore works courtside at a Denver Rockets basketball game.

COURTESY MOORE FAMILY

Late sports writer Ralph Moore works courtside at a Denver Rockets basketball game.

In the game’s final moments, we stole away to the otherwise empty arts department where we could watch the ending and cry more openly – win or lose – without peer judgment.

With 32 seconds remaining and Green Bay facing 4th-and-6 on the Denver 31-yard line, Brett Favre threw a short pass intended for tight end Mark Chmura. History says John Mobley broke up the pass, cementing the Broncos’ victory. After yelping, jumping and hugging, we watched the replay a half dozen times.

It didn’t look like Mobley came into contact with the ball in any of them.

“That was Grandpa Ralph,” my nephew said matter-of-factly. Who was I to argue?

The Ralph Box has been gently, progressively culled over the past 28 years down to photos, essential writings, press clippings, military memorabilia, letters and such. My one absolute rule: Anything he typed, or is written in his handwriting, never gets tossed.

One of Ralph Moore's proudest accomplishments was helping to establish Denver "Munylinks" tournaments – those involving city-owned public golf courses. Here Moore, left, helps present the 1965 Munylinks championship trophy to Herb Bolden at City Park Golf Course. At right is Joe Cianco, manager of the city's department of parks and recreation.

COLORADO GOLF ASSOCIATION

One of Ralph Moore’s proudest accomplishments was helping to establish Denver “Munylinks” tournaments – those involving city-owned public golf courses. Here Moore, left, helps present the 1965 Munylinks championship trophy to Herb Bolden at City Park Golf Course. At right is Joe Cianco, manager of the city’s department of parks and recreation.

There is his Denver Post column from 1961, demanding that the Colorado Golf Association finally break its color barrier and allow all golfers to compete in championship tournaments. (The week before, a Black golfer had been barred from participating in a state medal-play tournament.)

Ralph Moore

COURTESY MOORE FAMILY

- Ralph Moore

There is his profile of Dutch Clark, aka “The Flying Dutchman,” and Colorado’s first All-America college football player (“He comes as close to being the perfect athlete as anyone in the history of sports.”)

There is a letter written by a kid he coached in football at St. Anne’s grade school. There is another from University of North Carolina basketball legend Dean Smith offering us consolation after his death.

There is his 1984 date book, which I randomly flipped to May 14: “Lunch w/Arnold Palmer @ Cherry Hills C.C.” This was surely for an interview, because our family was way more Indian Tree than Cherry Hills. I know this because I also came across an income statement that shows Ralph raised eight kids on a Denver Post salary that never exceeded $30,000.

There’s a Post-It note from the morning after I won some high-school award that says: “John, thanks. I needed that. – Dad.”

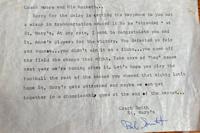

A typed letter from Bob Smith to fellow sport journalist Ralph Moore when the two were the head football coaches of the St. Mary's and St. Anne's grade-school football teams, respectively.

JOHN MOORE/DENVER GAZETTE

A typed letter from Bob Smith to fellow sport journalist Ralph Moore when the two were the head football coaches of the St. Mary’s and St. Anne’s grade-school football teams, respectively.

Now here’s one with an impossible twist: A typed letter from “Coach Smith.” Not Dean. This one was from Bob, coach of our grade-school football rival, St. Mary’s of Littleton. We played once a year. Coaches Moore and Smith instituted a traveling trophy that stayed in the possession of the most recent winning team. If St. Mary’s won, the trophy would be known for the next year as “The MaryAnne.” If St Anne’s won, it would be known as “The Anne-Marie.”

”I want to congratulate you and the St. Anne’s players for the victory,” Smith wrote. “You defeated us fair and square. … You came off the field champs that night. Take good care of her, ’cause, next year, we’re coming after it.”

Turns out, the coaches were pals and colleagues. “Coach Smith” was himself the renowned prep sports editor at The Denver Post, and he would finish his career working with me there.

Both of their sons now work at The Denver Gazette. In fact, the first editor who will read this very column is Robert Smith – son of “Coach Smith.” Not making this up.

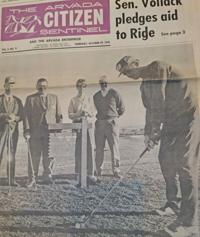

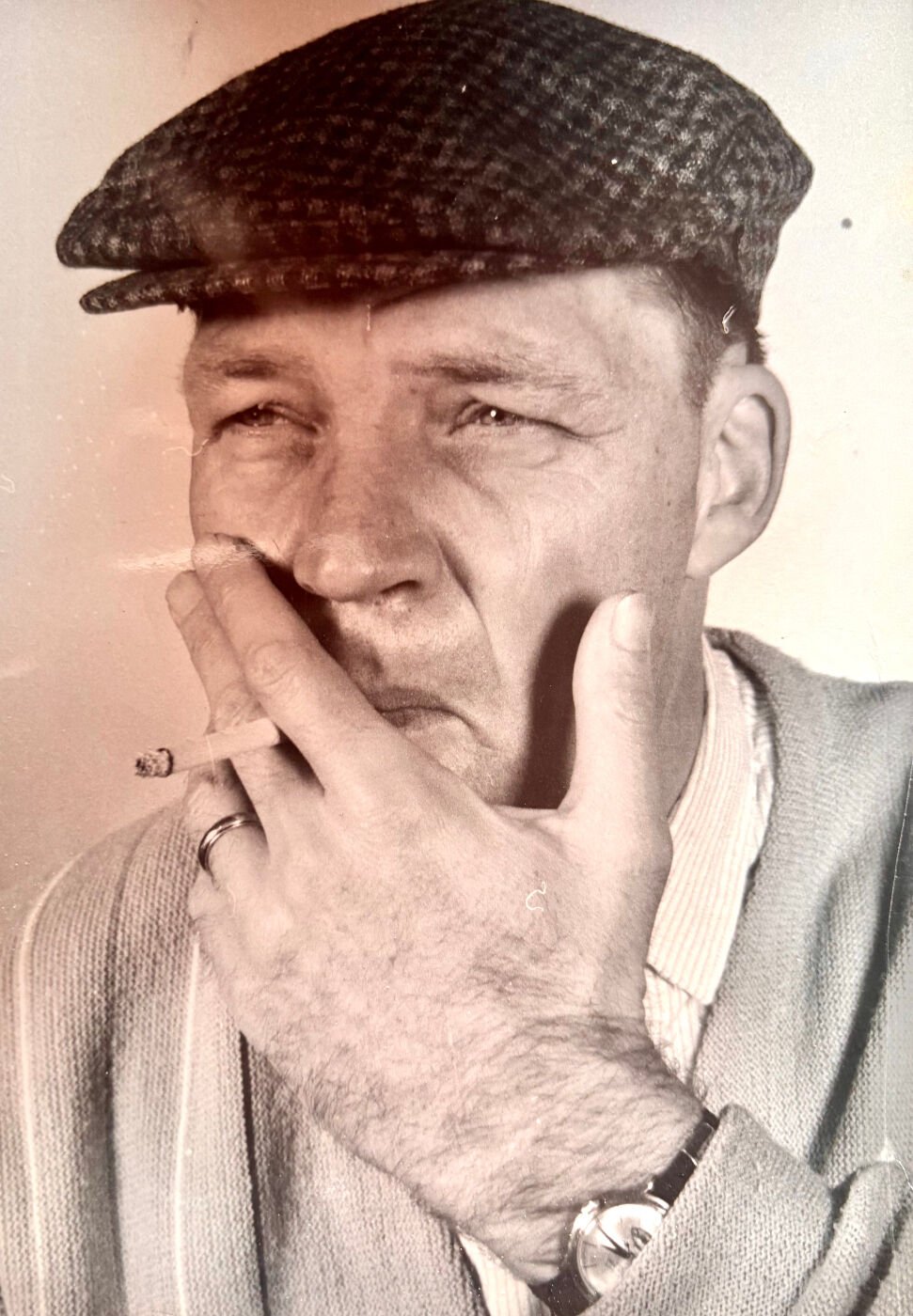

Golf reporter Ralph Moore served as vice president of the North Jeffco Parks and Recreation District that created the Indian Tree Golf Course, and was invited to be among the first to tee off in 1970. To his immediate right was the club's first golf pro, Vic Kline.

Arvada Citizen

Golf reporter Ralph Moore served as vice president of the North Jeffco Parks and Recreation District that created the Indian Tree Golf Course, and was invited to be among the first to tee off in 1970. To his immediate right was the club’s first golf pro, Vic Kline.

Are you kidding me?

Then, as if out of a movie, there it was: A seven-page typed essay that I either never noticed before or was wiped clean (along with much of my memory) by a 2009 brain injury. It was titled: “What I Would Like to Be Remembered For.” By Ralph Wayne Moore Jr.

C’mon! The day before your dad’s 100th birthday, 28 years after the death of the man who remains the single biggest influence of your life … you come across a random essay titled “What I Would Like to Be Remembered For”?

Hollywood would never believe this sentimental shlock.

Only, there it was, typed out in a hundred precious bullet points: The chronology of a life.

No. 1, with a bullet (point), are simply the names of the eight kids my father raised with my mother: “Kathy, Theresa, Brian, Mike, Pat, Danny, Kevin and Johnny.”

No. 2: Remaining faithful to his wife through the full duration of their marriage.

This life story begins at conception – and for my dad, that took place as his parents were honeymooning and the Moffatt Tunnel was under construction. (We used to not tell that story. Now we can’t tell it enough.)

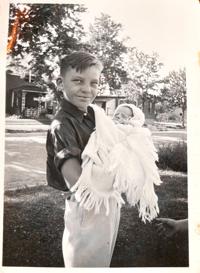

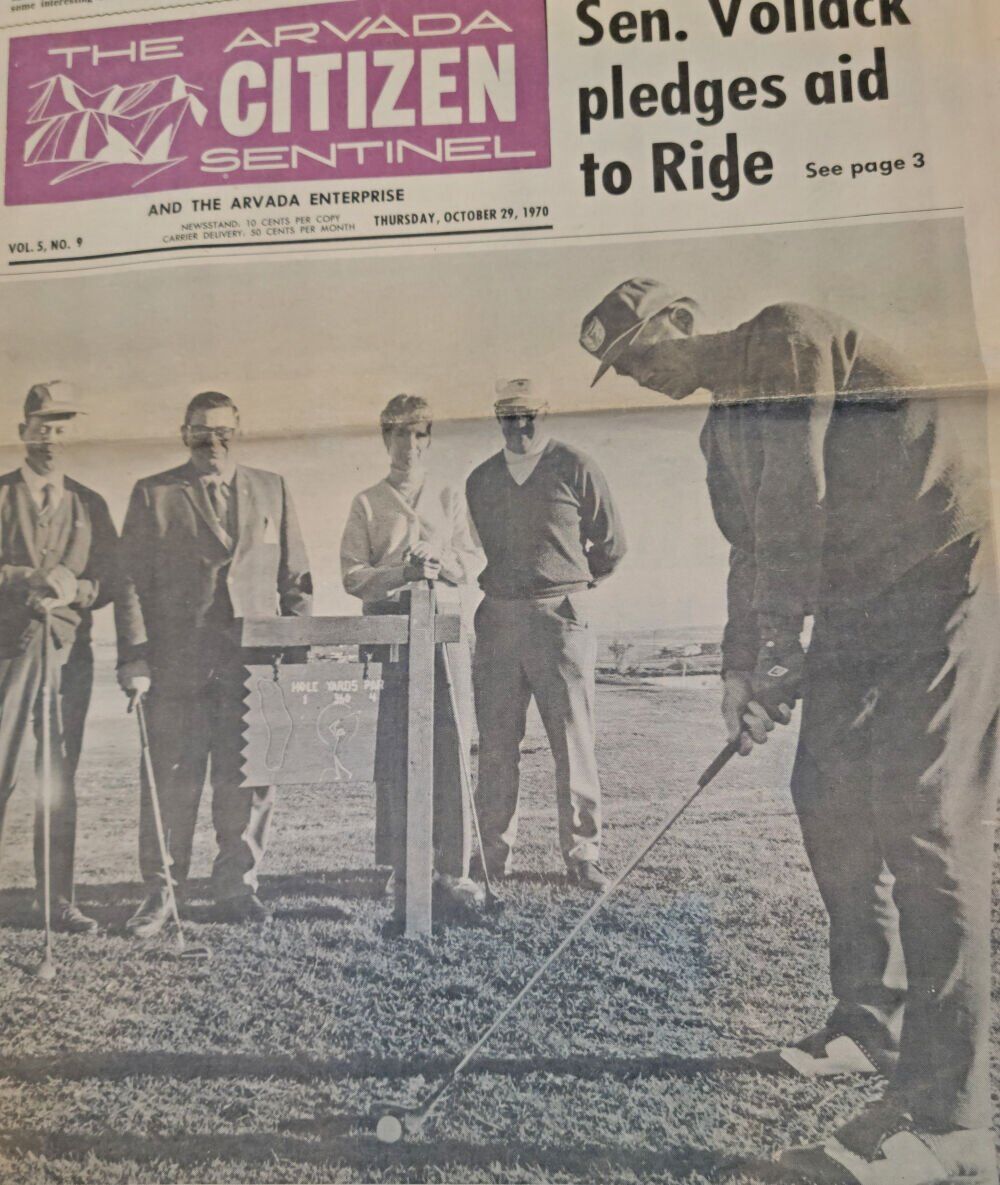

Ralph Moore at age 11 holding his brother, Bob.

MOORE FAMILY

Ralph Moore at age 11 holding his brother, Bob.

There are stories of serving as an altar boy at the 5:15 a.m. Catholic Mass. Of Sunday peaches and ice cream with Grandma Marie before being sent to live with relatives in Los Angeles when the Depression wiped out his father’s wages. There are endless references to an Old Denver long relegated to library microfilm: The Trocadaro Ballroom, El Patio, Rockybilt Hamburgers, malts at Lande’s, car hops at the Welcome Inn, beer sessions at the Club 44, Class-A baseball at Bears Stadium.

• Sister Francis Borgia, who taught me typing and coached me to victory in Archbishop Vehr’s essay contest.

There are stories from serving for four years in World War II as a Navy Lieutenant J-G, like playing his first round of golf in Shanghai, China, in 1944. The nine-hole course was cut inside a horse-race track – and it doubled as the chopping block for sold-out public beheadings between races. “The executioner’s swing,” dad observed with the keen eye of a future golf reporter, was much more fluid than his own. “Nice, clean cut. Good backswing. Nice follow-through.”

He writes of meeting Dorothy Heiser and her family in Shanghai. He writes of trading Dorothy fifths of gin for quarts of pasteurized milk. He writes of later having dinner with the Heisers in their home after the Fourth Division Marines freed them following six years in a Japanese prison camp.

• Watching from the Great Wall as Mao’s Communist Army overwhelmed the First National Army.

• Repatriating Korean slaves back to Korea, a land some of them had never seen. Repatriating Japanese to Japan, a land some of them had never seen.

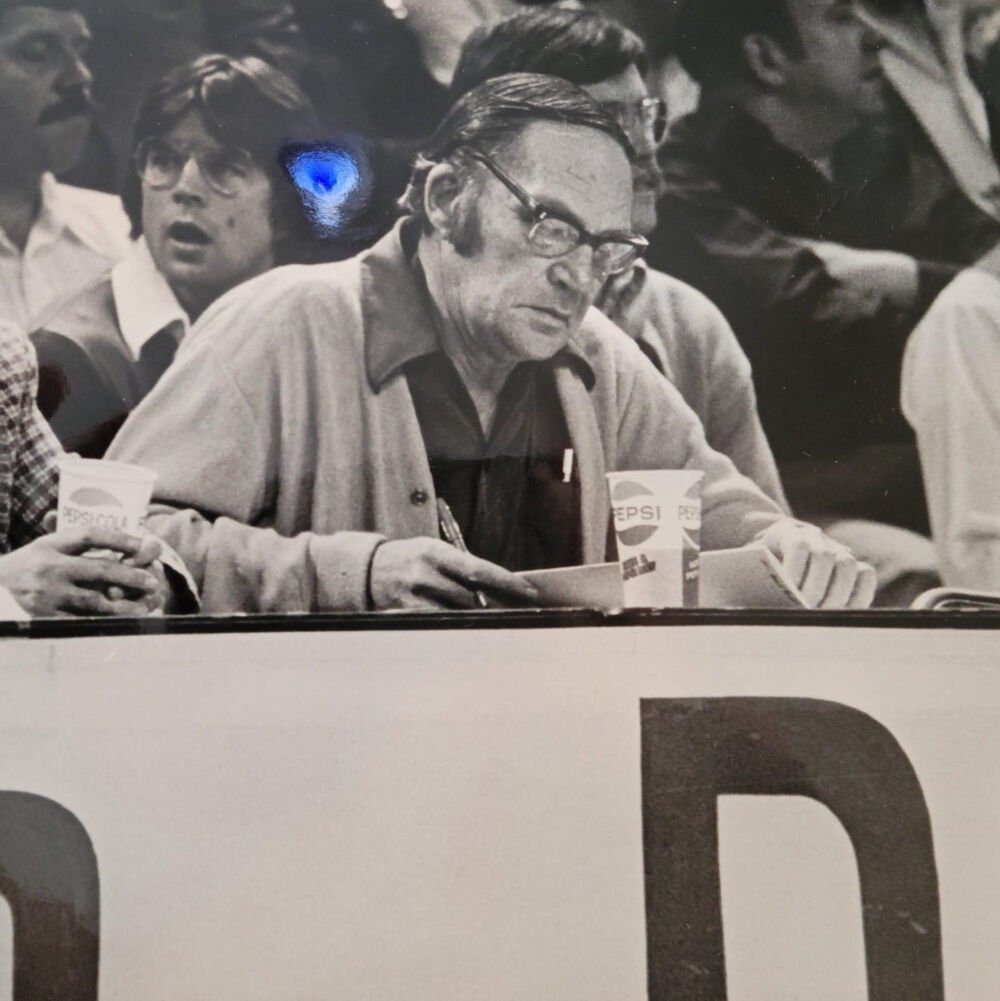

One of Ralph Moore's favorite assignments was covering Ben Martin and the Air Force Academy football team for The Denver Post. That included Air Force's first-ever bowl game, a 0–0 tie with TCU in the 1959 Cotton Bowl .

COURTESY AIR FORCE ACADEMY

One of Ralph Moore’s favorite assignments was covering Ben Martin and the Air Force Academy football team for The Denver Post. That included Air Force’s first-ever bowl game, a 0–0 tie with TCU in the 1959 Cotton Bowl.

He writes of joining the Denver Post as a copy boy in 1948. His first byline was a six-paragraph theater review (Of “The Winslow Boy” at the Elitch Theatre) before becoming a sports writer. By contrast, my first byline in The Denver Post was in the sports pages before becoming the paper’s 12-year theater critic.

He writes of covering the origins of professional basketball in Denver, from the start of the Denver Rockets in 1967 through the start of NBA’s Denver Nuggets in 1974 through his retirement in 1984.

Perhaps my favorite bullet point of the entire essay is this one:

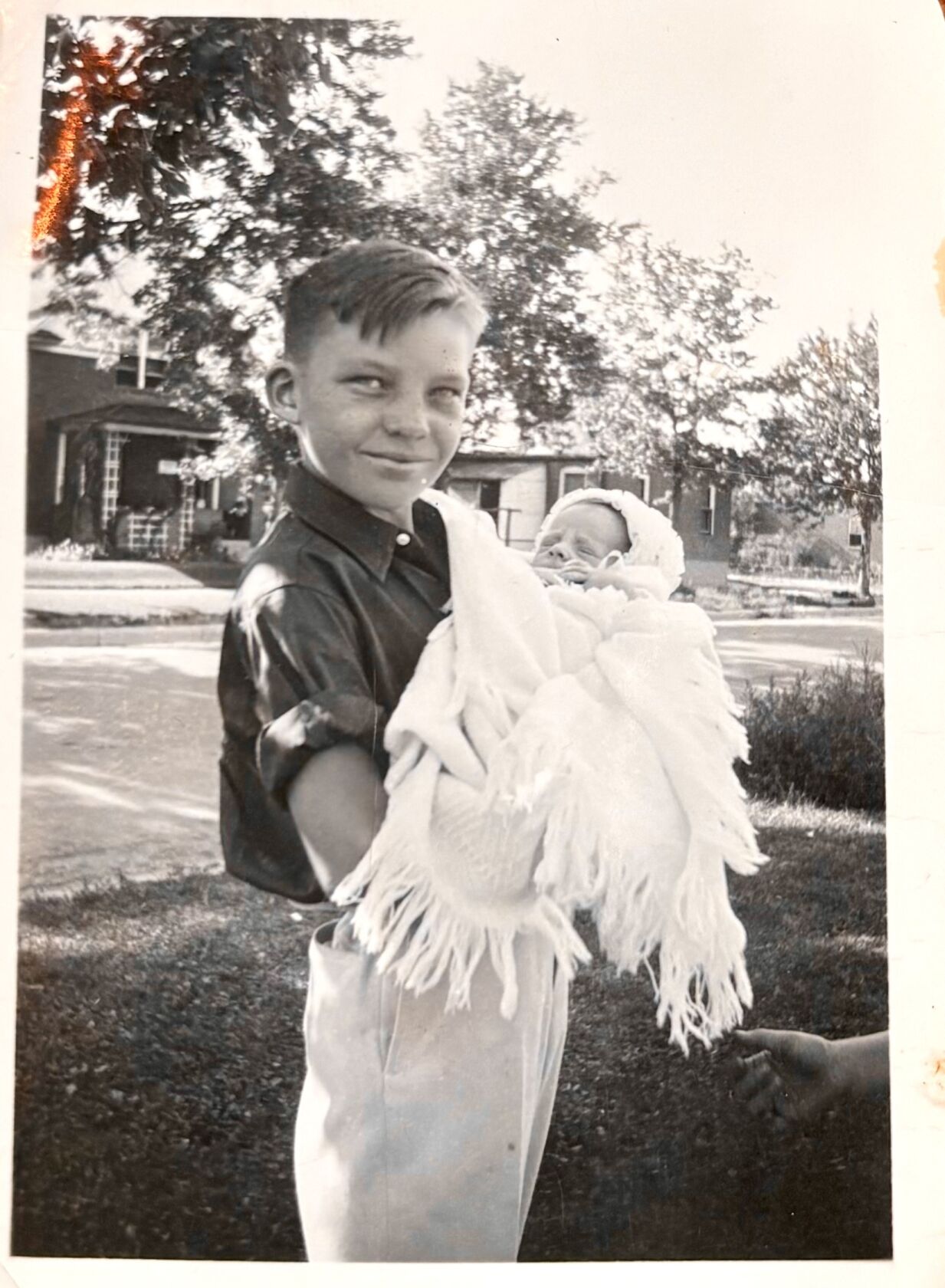

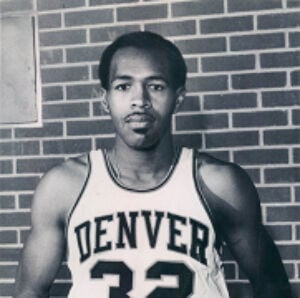

Larry Jones was the Denver Rockets' first superstar. He played three seasons from 1967-70 and was nearly arrested in Pittsburgh over a contract dispute.

COURTESY DENVER NUGGETS

Larry Jones was the Denver Rockets’ first superstar. He played three seasons from 1967-70 and was nearly arrested in Pittsburgh over a contract dispute.

• The Larry Jones Caper in Pittsburgh, and the process-server who sat on the Rockets’ bench looking for him. (He wasn’t able to serve the papers because no one would tell him which one Jones was, and they squired him away before he could find out on his own.)

This sounded like a scene right out of “Catch Me if You Can.” The journo in me needed to know more about what happened in Pittsburgh on Oct. 27, 1967.

I knew Jones was the first superstar in Rockets history, averaging 25.4 points over three seasons from 1967-70. I also knew that, in 1967, players’ names were not yet listed on their jerseys, so I particularly loved the idea of Jones’ teammates “squiring” him from the court to the locker room to the befuddlement of his pursuer.

Confusing things, though, was a more recently reported account that says Jones had been tipped off about the subpoena, so he never even got off the plane in Pittsburgh as the Rockets were being clubbed by the eventual ABA champion Pipers, 91-77.

Which version is true? I trust my father’s version, because he would have been there. But I really did try to get to the bottom of it. I discovered a recent podcast that revealed Jones is 82 and still doing quite well in Columbus, Ohio. Host Tim Brown was kindly trying to arrange for us to talk when the merciless deadline for this column passed. (Check back for updates.)

Ralph Moore, right, with fellow local newspaper legend Harry Farrar, at a game.

COURTESY MOORE FAMILY

Ralph Moore, right, with fellow local newspaper legend Harry Farrar, at a game.

I was able to determine that Jones, a devout Christian, was not wanted for any nefarious reason. The year before, Jones had been playing in the Eastern League – the minor-league precursor to the Continental Basketball Association. He wanted out, so he wrote to “just about every team in the ABA” offering his services, “and Denver was the only team that responded,” he has said.

But the Eastern League didn’t take kindly to losing its star player, so it disputed the legality of his contract with Denver, which paid him a whopping $10,000.

Easter in July

There are so many magical Easter eggs contained in the essay’s seven pages. Like the time Ralph was locked inside the Houston Astrodome. … Attending a seven-hour opera in Shanghai and, a few months later, singing the theme song from the Broadway musical “Annie” while marching across Michigan Avenue. … Scooping the world that the ABA held its first draft – in complete secrecy. Seriously, no one was told. (How does that happen?) But that’s how I learned the Rockets actually drafted (for naught) future NBA legend Walt Frazier.

For my family, the most meaningful entries come on the last few pages, where Ralph lists little slivers of fatherly pride.

• Reading Kathy’s poetry … Mike hitting three baseballs out onto the Wadsworth Bypass in one game! … Sweating out Theresa’s cheerleader tryouts. … Johnny’s valedictorian speech at the Regis graduation.

But the absolute gold of the whole thing are the unprecious gems Ralph laid down that we will banter about with each other for the rest of whatever time we have left. Gems like:

• Getting everyone out of jail a time or two.”

• Mike’s winning efforts in the county swim meet after his arrest and conviction for shoplifting a candy bar.

• Kevin and Danny selling pages out of a pornographic French magazine.

(How did I not know about that one?)

The essay provides both a generational snapshot of a rich life well-lived, and a keepsake for all descendants to come. Reading it, I kept thinking, “If I taught a writing class at Lighthouse Writers Workshop, this is an exercise I would recommend that everyone do.” I know I will.

We figure that our dad probably wrote all of this down sometime around 1990-95.

But on Monday, July 7, 2025, as we sat around the gravestone taking turns reading it out loud, it sure seemed like an incredible, incredulous, fun and funny posthumous 100th birthday gift to all of us from the birthday boy himself.

Thanks, Ralph.

• Learning how to spell

Ralph Moore, the dean of Nuggets beat writers, worked on press row for many years of Denver Nuggets (and Rockets) games.

Courtesy Moore Family

Ralph Moore, the dean of Nuggets beat writers, worked on press row for many years of Denver Nuggets (and Rockets) games.

John Moore is The Denver Gazette’s senior arts journalist. Email him at john.moore@gazette.com