Rural Reckoning | What does rural Colorado want to see in the next governor?

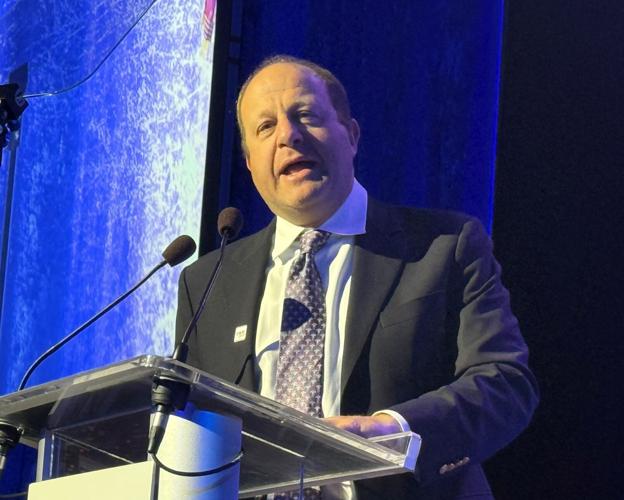

In 2026, Colorado voters will head to the polls to select the next governor. With Gov. Jared Polis terming out, that new state leader will take over at the start of 2027.

When Colorado Politics asked Polis what advice he is going to give to his successor, he smiled and said that, with 18 months left on his term, he’s not ready to say — he feels like there is plenty to do himself, he said.

Others, however, offered plenty of advice for Colorado’s next chief executive.

They said the governor must cultivate the economies of rural communities, home to ranchers and farmers, even if the political power largely resides in the Front Range, the center of Colorado’s population. As such, they added, the governor must work to ensure the rural economy is resilient.

They said the next governor should make it a point to understand rural communities — by spending time there.

And the next governor should be cognizant that rural Colorado offers a different lifestyle, often removed from the woes and conveniences of the state’s urban corridors.

As he enters the final year in office, many say Polis’ actions affecting rural Colorado will help define his legacy.

The place to ‘create your own dream’

Rural Colorado is the heart of the state, said former governor and now a Democratic U.S. Sen. John Hickenlooper.

It’s not just about food production — and Colorado is a leader, whether it’s cattle, hogs, dairy, or corn, he said.

Rural Colorado “provides a lot of the values and quality of life that people look for and expect,” he said.

Hickenlooper recounted a campaign trip to Sterling in 2010, where he met with the president of Northeastern Junior College. The president asked him where he was heading next, and Hickenlooper said Burlington and Lamar.

“Wow, you’re really going into rural Colorado,” the president said.

He advised Hickenlooper to go to a park just outside of town that has four interconnected baseball diamonds, with bleachers and barbecue pits.

This happened on a Tuesday night, Hickenlooper recounted, and games went on at all four diamonds: Little League, women’s softball, a high school game and a “pony league” game. Barbecues went on around the fields, too.

“This quality of life was just an hour and a half from Denver,” Hickenlooper said. “This was a power that people didn’t recognize.”

After becoming governor, Hickenlooper and Dean Singleton, the former publisher of the Denver Post, came up with the Pedal the Plains bike tour so that Front Range residents could experience that rural quality of life.

Colorado already had several bike tours in mountain communities, but the Eastern Plains was not part of the mix.

Rural Colorado is also a place to find entrepreneurship, Hickenlooper said, adding that’s something that resonates with the former geologist and brewery owner.

He said there are no better entrepreneurs than Colorado’s farmers and ranchers. They must invest every year so that they have enough profit to continue their business, he explained.

“They have to raise capital every year, all new investments, assess the risk versus the reward, the crop they’ll grow and the weather,” he said, adding all that can get washed away with one storm.

He once visited northeastern Colorado with the late John Stulp, the state first water czar, and met a farmer who was waiting for one last good rainstorm. The farmer was elated when that storm hit, but then it turned to hail and 60% of the crop was gone.

“That kind of entrepreneur gets back up,” Hickenlooper said, calling it a model for people in the tech business.

One farmer-rancher, Keith Bath of Morgan County, put up a sign for Hickenlooper in that 2010 campaign. One of his neighbors commented on it, and Bath’s reply, according to Hickenlooper, was “he’s half farmer.”

A governor has a vested interest in making sure the rural economy is strong, which inspires the rest of the state, he said.

That led to his efforts to promote “bottom up” economic development, at a time when Colorado was No. 42 in job creation, resulting in conversations in all 64 counties and plans that came out of as many as 60 of them, he said.

This isn’t just a state of ski resorts, Hickenlooper said.

“It’s a place to create your own dream, whether in the city or in the rural areas,” he said.

Colorado is a diverse state, but “if we think of ourselves as a state united, we do better,” he added.

Visit rural Colorado

Visiting all 64 counties — all four corners of the state — is crucial to being an adequate state leader, said Sen. Cleave Simpson.

Recently named minority whip, the Republican senator from Alamosa half-jokingly advised the future governor of Colorado to “come visit me” at his ranch.

Simpson said he is constantly inviting members of the state legislature and other state officials to drop by rural Colorado to see for themselves what those communities need.

Former Gov. Bill Ritter said he does not doubt that Polis has had a more unique run as governor than others.

The COVID pandemic was a challenge, he said.

However, Ritter is most sympathetic to Polis regarding the wolf reintroduction program that has strained the state’s relationship with the ranching and farming industry and which many said further created frustrations in rural Colorado.

Ritter, who served between Owens and Hickenlooper, said one of the toughest things to do as a governor is to implement a voter-approved initiative. For him, it was marijuana; for Polis, it is the wolf reintroduction program, he said.

While voters approved medical marijuana before Ritter took office in 2007, it was his administration that had to create policies to implement and regulate it.

“As governor, you have to live with what the voters, you know, kind of hand to you,” Ritter said. “It’s just the hand to deal with. I do know a number of people who are part of the division of parks and wildlife that work for Polis, and they’re spending an inordinate amount of time on wolves, and you know, it was handed to him.”

Ritter said people can’t necessarily look at the wolf situation and conclude whether Polis did a good or bad job — on something he didn’t ask for.

“He actually inherited this from the voters of the state,” Ritter said. “Now, he’s got to cope with it. And, you’re exactly right, rural Colorado and farmers and ranchers did not want it. But it happened. I think it just landed hard on rural Colorado.”

For future governors, Ritter said Colorado’s population and voting power may be located along the Front Range counties, but the future governor cannot ignore the economic impact that ranching and farming have on the state.

Ritter said he got a good grasp on the needs in rural Colorado by being engaged.

“My sense of rural Colorado was fed by my own experiences in my childhood and adolescence,” Ritter said.

Ritter said it is essential to visit and listen to understand the needs of rural Colorado.

As governor, he gained a deeper understanding that, during recessions and beyond, the financial struggles of farmers and ranchers are a constant worry. He noted that a study once showed him the 20-year profit margin for them was around 2.5%.

Rural Colorado, home to ranchers and farmers, has emerged as a key target in the energy sector, with Ritter noting that transitioning from 200 megawatts to 5,000 megawatts of wind power is a significant challenge.

The ranching community also had some advice for the future governor.

Marsha Daughenbaugh, from her ranch in Steamboat Springs, said, “I would like to see someone who has an understanding of what agriculture provides to Colorado. Someone who respects that and tries to work with ag organizations to make sure that this agriculture base will stay here.”

Mark Harvey, a potato farmer and winemaker and former member of the State Land Commission, said he feels that Polis has worked hard to understand the challenges facing rural Colorado, and the future governor will have to do the same.

“Ag communities often feel they are left behind economically and socially,” he said. “The remoteness of rural communities sometimes hides their real value to society. Most of the press and hubbub is centered around cities, but most of what we eat is produced in rural communities.”

Editor’s Note: This is the fourth and final set of a series examining Colorado’s urban-rural relationship. Follow all the stories in the series here. Hap Fry and Rachael Wright contributed to this report.