Supreme Court orders Colorado sheriff to turn over video surveillance of attorney-client meetings to defendant

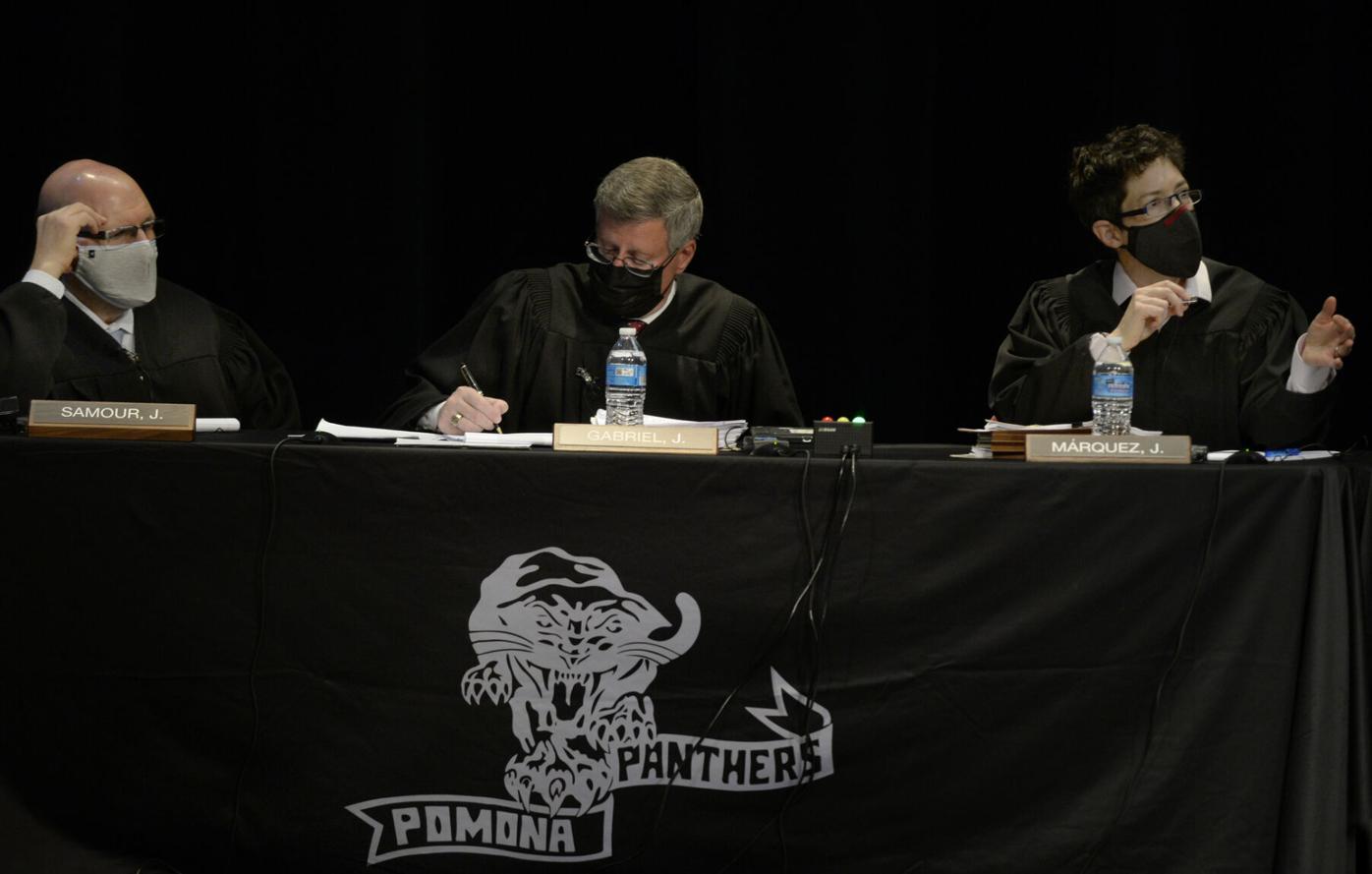

ARVADA, CO - OCTOBER 26: The Colorado Supreme Court, including left to right, justices Carlos A. Samour Jr., Richard L. Gabriel, and Monica M. Márquez, hear two cases at Pomona High School before an audience of students on October 26, 2021 in Arvada, Colorado. The visit to the high school is part of the Colorado judicial branch’s Courts in the Community outreach program. (Photo By Kathryn Scott)

Kathryn Scott

The Colorado Supreme Court has ordered the Archuleta County Sheriff’s Office to turn over the videos it recorded of a defendant’s jailhouse meetings with his attorneys — revelations that already led to one mistrial and could result in sanctions or the removal of the district attorney’s office from the murder case going forward.

In an unsigned order on Feb. 28, the justices granted Christopher Ross Maez the relief he asked for: to receive the jail’s surveillance of his defense team without having to funnel it through the prosecutor’s office first. Maez’s attorneys called the sheriff’s videotaping a violation of his Sixth Amendment right to counsel, and suggested they also ran afoul of the Colorado law that mandates jailhouse consultations be private.

The order did not address those claims, but nonetheless enables Maez to use the videos in support of his efforts to dismiss the criminal charge against him or alternatively have a special prosecutor take over the case.

“What happened in this case is outrageous and should concern everyone in Colorado,” said Ann Roane of the Colorado Criminal Defense Bar. “That agents of an elected district attorney are so oblivious to the fundamental right to a lawyer, which obviously includes the right to talk privately with that lawyer, suggests that law enforcement and prosecutors are forgetting the oath they swear to uphold the constitutions of Colorado and the United States.”

Christian Champagne, the elected district attorney for Archuleta County, said he is unable to comment on the underlying criminal case.

Maez stands accused of murdering Millie Mestas in 2019. While incarcerated before trial, he met with members of his defense team approximately 60 times.

In July of last year, jail Commander Ed Williams learned a portion of a police report was discovered in the jail’s housing unit, and the paper identified an informant. Believing the informant’s safety was at risk, the jail initiated an investigation. Williams heard someone on Maez’s legal team allegedly slipped Maez the report during a meeting.

“I reviewed CCTV video footage of that legal visit,” Williams wrote. “It should be noted that the CCTV system does not capture sound it only captures video thus staff is unable to hear any conversations between the inmate and his legal team per federal statutes.”

Williams reportedly saw Maez receive the report by zooming in to examine a paper with roughly the same formatting as the one recovered in the jail.

On Aug. 26, the day of jury selection for Maez’s trial, the prosecution told the defense about Williams’ actions, revealing that the sheriff’s office, as the investigating agency for the murder case, had viewed the defense’s attorney-client discussion.

“It doesn’t matter how much they saw,” said Ingrid A. Alt, one of Maez’s attorneys. “What we know is that the jail is recording, which they shouldn’t be doing, and learning information about what we talked to our client about.”

Champagne, who was prosecuting the case himself, said he had just learned of the sheriff’s recordings and his office had nothing to do with them.

“I would think that any time there’s an attorney and a client, that there wouldn’t be any surveillance at all,” observed Chief Judge Jeffrey R. Wilson. “I mean, maybe some occasional checking to make sure everything’s okay. I would be concerned about the videotaping.”

Alt clarified that the video monitoring was not necessarily concerning, “but recording it and then using it to provide information to the district attorney’s office — that’s the problem.”

Wilson declared a mistrial. Months later, he ordered any meeting videos that captured sound to be turned over to the defense directly. However, for the other footage, without audio, “the DA shall obtain and provide” it.

Maez quickly appealed to the Supreme Court.

“Mr. Maez’s defense will be catastrophically damaged if this Court does not intervene before dozens of privileged communications containing not just facts but also defense preparation and trial strategy are disclosed directly to the prosecution in advance of trial,” his attorneys wrote. They argued that body language, lip reading or zooming in on specific evidence would illuminate what the defense team talked about even without the accompanying audio.

Champagne countered that the sheriff’s office’s actions “were appropriate” given that Williams was investigating a potential crime with the contraband police report, and that the prosecution should be allowed to defend itself against sanctions by seeing the videos, too.

The Supreme Court endorsed the proposal of Maez’s lawyers: The sheriff’s office will disclose the videos to the defense, and the only way the prosecution can see them is if the trial judge screens the footage first and determines which videos to provide to the district attorney.

Sheriff Mike Le Roux told Colorado Politics that the jail has since moved meetings between detainees and their attorneys into a smaller room that is not video monitored on the inside. He clarified that the surveillance is not necessarily recorded for storage, but captured continuously and overwritten after a designated period.

Le Roux was unaware of other jails that record attorney-client meetings, but he believed his office did not violate Maez’s attorney-client privilege in its investigation of the contraband document.

“Our stance is we were investigating an inmate safety concern within the jail, and the act of Commander Williams was, I suppose, an administrative investigation to potential inmate safety. We believe he carried out his duties for the best interest of inmates within the jail,” he said.

The executive director for the County Sheriffs of Colorado did not immediately respond to a question about whether other jails record defendants’ interactions with their attorneys. Maez’s lawyers similarly did not respond to a request for comment.

The case is People v. Maez.